Many noncitizens plan to avoid the 2020 Census, test run indicates

The U.S. government is conducting a test run of the 2020 census in Rhode Island's Providence County, where many noncitizens living in Central Falls, R.I., say they're planning to avoid participating in the national headcount. (RussellCreative/Getty Images)

Updated 3:52 p.m. ET, May 17

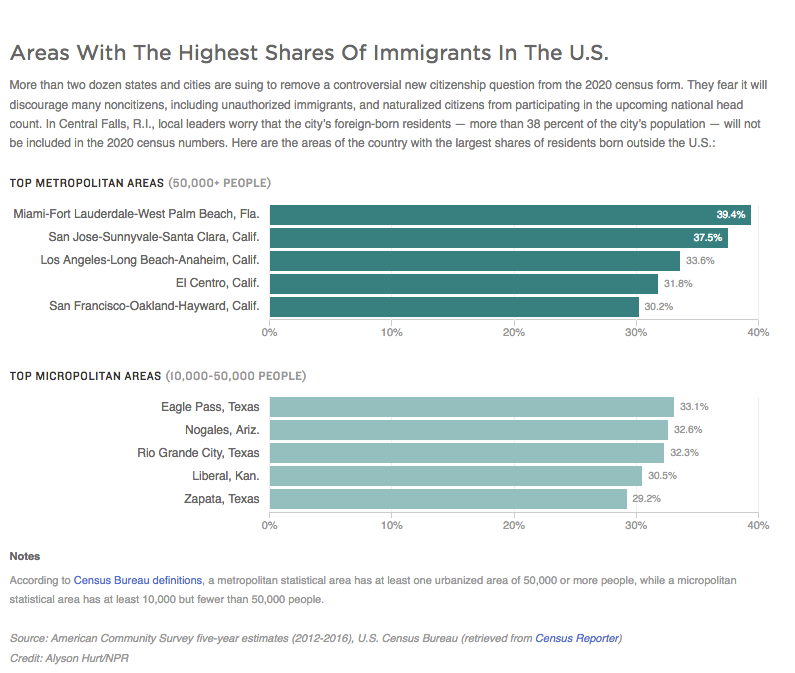

For the country’s only test run of the 2020 census, leaders in Rhode Island’s Providence County are struggling to drum up participation among one of the hardest-to-count populations in the U.S.: unauthorized immigrants.

The U.S. Constitution requires a headcount of every person living in the U.S. every 10 years. The Census Bureau has sent multiple mailings and fanned out close to 1,000 door knockers across Providence County to practice making a complete tally in preparation for 2020.

But local officials say the rise of anti-immigrant rhetoric and increased immigration enforcement under the Trump administration – not to mention the last-minute addition of a controversial, new citizenship question to the 2020 census form – have set the upcoming national census on a path to an undercount of noncitizens, especially those living in the country illegally.

“We need accuracy”

In an old New England town such as Central Falls, R.I. – one of the test sites for the 2020 census – every national census counts because every dollar counts. An estimated $800 billion in federal funds are distributed every year based on census data.

“It’s real facts,” says James Diossa, the mayor of Central Falls. “We need accuracy so that we can provide for our residents. But if you have information that’s not true, it’s going to affect all of these quality-of-life issues.”

Census numbers, Diossa says, recently helped Central Falls win state funds to clean up its only two athletic fields, where last year the city found lead, arsenic and other industrial contamination in the soil.

“If we don’t know how many people are here, we can’t really make an argument on why it’s so important to understand that this is a heavily-used field,” he explains, standing on the same field at Macomber Stadium where he once played soccer as a student.

Diossa says he hopes Central Falls kids keep kicking balls on the field like he did growing up. To make sure there’s enough funding for the city’s fields, roads and schools, he’ll need all of Central Falls to be counted for the 2020 census.

“The elephant in the room”

The last headcount in 2010 included just over 19,000 residents, with about 60 percent identifying as Hispanic or Latino. Over the years, this majority-Latino city has helped bolster the entire state of Rhode Island.

“It’s the elephant in the room,” says Gabriela Domenzain, director of the Latino Policy Institute at Roger Williams University in Providence, R.I. “This is why our state has continued to have the representation it has at the federal level because Latinos, just like they do many places in the U.S., are making up for the fact that folks are getting older and not having children.”

But Domenzain and other leaders in the state are worried. They’re closely watching the test run of the 2020 census because the stakes are high in Rhode Island. The state may lose political power on Capitol Hill if the 2020 census finds a significant dip in population numbers, which are used to distribute seats in the U.S. House of Representatives among the states after each headcount. After the next reapportionment, the two House seats belonging to Rhode Island right now could drop down to one.

The Census Bureau says the test run of the 2020 census is going as planned for the most part. Despite technical hiccups with the iPhone app census workers are using in the field that have been corrected, there have been no “showstoppers,” the bureau’s head of the 2020 census, Albert Fontenot, announced at the bureau’s last quarterly update on preparations in April.

“The objective of the test is to test our systems, our system integration, the processes and procedures, and not to drive to a particular response goal,” Fontenot said last month at the Population Association of America’s annual meeting in Denver.

Still, Domenzain says many Latino residents in Providence County are refusing to be counted for the census test – even for one that does not include a citizenship question, which was approved for the 2020 forms in March, after test questionnaires were already mailed out to households.

“People are scared,” Domenzain says.

The harm of a citizenship question?

The Latino population in Central Falls includes citizens and noncitizens, both documented and not. Fear of the census among undocumented immigrants is rippling out to their relatives who have green cards or U.S. citizenship, Domenzain adds. Many are afraid of giving their information to the federal government and of getting their mixed-status families on the government’s radar.

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who oversees the census, approved the request for a census citizenship question from the Justice Department. The DOJ says it needs a better count of voting-age citizens to better enforce the Voting Rights Act’s provisions against racial discrimination. But Domenzain is not convinced.

“They’re putting a citizenship question on the census to further inflict harm, emotional and psychological, on a community that they have proved time and time again they don’t want here,” she says.

The Census Bureau has asked all households about U.S. citizenship before, but the last time was back in 1950. Research by the bureau suggests that asking about citizenship now could lead to an undercount, especially among immigrant and Latino populations. More than two dozen states and cities — including Central Falls — are suing to remove the question.

“The president wasn’t threatening us”

Whatever happens with these lawsuits, many unauthorized immigrants in Central Falls have been grappling with what to do ever since the census test questionnaires started landing in their mailboxes in March.

“The biggest worry is that you have to write down your name,” Jesús says in Spanish, as he mimics filling out a census form by hand. We’re using a family name for Jesús because, as an undocumented immigrant, he fears deportation.

Jesús laughs easily and gestures with his hands when he speaks. He says he has lived in Central Falls for a decade. Back in 2010, when President Barack Obama was still in office, Jesús participated in the census.

“We were happy to fill it out then,” he says. “The president wasn’t threatening us.”

But this time around, with President Trump in the White House, he says the census feels like a threat to him and to his three roommates, who are also undocumented.

“What if our information is misused and lands in the hands of immigration?” he asks.

“No one wants to open the door”

Federal law prohibits the U.S. Census Bureau from sharing information that would identify individuals to other government agencies, including ICE, Immigration and Customs Enforcement. But it can share information about specific demographic groups down to the neighborhood level.

Since the census test began in March, Jesús and his roommates have received multiple notifications from the Census Bureau. The envelopes included a warning in both Spanish and English: “YOUR RESPONSE IS REQUIRED BY LAW.”

The first two mailings went straight to the trash can, Jesús recalls. But receiving the third mailing pushed the four roommates to sit down and debate about the census. After work one evening, they talked through the pros and cons.

“Some raised concerns,” Jesús says, but then the four men voted unanimously to complete the test census form and mail it back. If they hadn’t, a census worker would’ve probably stopped by their house to follow up.

“You never know if it’s ICE or police knocking. No one wants to open the door,” he says with a nervous chuckle.

“Looking behind you all the time”

Jesús says he and his roommates felt conflicted, but they agreed it was easier to just fill out the form and forget about it. That’s a gamble that many other undocumented immigrants are not willing to make, including Humberto.

He’s lived in Central Falls since he was a teen, when he moved to join relatives who were already living in the city.

“I don’t know why they picked Rhode Island. It snows too much,” he says with a laugh. “But it’s nice. I love this state.”

We’re using a family name for Humberto because he, like Jesús, is afraid of being deported. He warns that the new citizenship question will keep more unauthorized immigrants from participating in the 2020 census.

“After you answer that question saying that you are not a citizen, you’re going to be looking behind you all the time,” he says.

Humberto says he understands, though, that if the 2020 census does not count all of his fellow residents of Central Falls, his beloved city stands to lose federal and state funds for its schools and other institutions. But he says, “People who live here day by day are thinking, ‘Are we going to be here tomorrow?’ ”

The “big risk”

At city hall, the mayor of Central Falls is trying to take the long view of the census. As the 2020 headcount draws nearer, he’s facing a potential crisis: Low census numbers could translate into less federal and state funding.

Many of the buildings in his city could be mistaken for single-family homes — until you spot the clusters of mailboxes hanging beside each door. In fact, it’s one of the most densely populated places in the country.

“We want these folks to participate. We want them to get counted,” Diossa says, while acknowledging the “big risk” to privacy that his residents are facing with the upcoming census.

“We all know that that information can’t be shared,” he adds. “But you don’t know whether those laws can be changed. And that’s the concern.”

The mayor says he’s stuck. He understands why many in Central Falls do not want to give their information to the Census Bureau. And yet he knows he needs that same information to run his city.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))