How people with low income pay the steepest price when inflation hits

A customer shops at at a grocery store on Feb. 10, 2022 in Miami, Florida. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Four-dollar gasoline and five-dollar hamburger are putting a squeeze on Tanya Byron’s pocketbook. But it’s the rent that really stings.

“It’s pretty depressing,” says the Jacksonville, Fla., travel agent, sitting in the tiny dining room that doubles as her home office. “I make $42,000 a year, and I can barely afford a one-bedroom apartment.”

The rising costs of housing, food and other necessities are big drivers of inflation, and they fall especially hard on lower-income Americans, posing a growing challenge for President Biden and the nation’s top economic policymakers.

A report on consumer prices from the Labor Department on Wednesday is expected to show the annual inflation rate easing somewhat in April from the previous month but remaining above 8%, near a four-decade high.

In Jacksonville, apartment rents have jumped 23% in the last year, according to Realtor.com.

“I feel like there should be some kind of cap on the percentage that a landlord can raise the rent if they haven’t done anything,” says Byron, whose own apartment dates from another period of soaring prices.

“It was built in 1976, and they have not updated anything,” she says. “The doors and baseboards are painted brown. It’s clean, but it’s very basic.”

Worrying about the future

Byron had hoped to move into a condo by now, but with real estate prices climbing rapidly and mortgage rates topping 5.25%, buying a home feels out of reach.

“I’m genuinely worried about the future,” Byron says. “What’s going to happen to the people making $15 and $18 an hour and the single mothers and people who have mouths to feed? It’s very scary to me.”

When inflation is high, everyone pays the price, but research suggests that lower-income families suffer the most.

“Typically food and gasoline and housing are a bigger share of total spending for lower-income households than for higher-income households,” says Dan Sichel, an economist at Wellesley College.

There’s another critical factor, Sichel adds.

Those with lower incomes tend to pay higher prices, even for similar items. They may be less able to travel to cheaper stores, take advantage of seasonal discounts or “get the giant package of toilet paper to stash in the basement when it’s on sale.”

Sichel chaired a committee from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine that recommended the Labor Department try to reflect those realities as part of an effort to modernize the way the government measures the cost of living.

“What people are paying for similar items at different stores is very important for understanding inflation inequality,” Sichel says.

Rethinking inflation

The committee recommended other ways to improve the way the government measures inflation, including more frequent updates to the basket of goods and services used to track prices.

Right now, the basket is adjusted only once every two years. That can miss big swings in consumption patterns like those that have occurred during the coronavirus pandemic, when Americans suddenly bought fewer movie tickets but more streaming subscriptions, for example.

Any effort to update the inflation measure is likely to attract outsize attention at a time when the consumer price index is front-page news.

“I think the stakes are very high right now,” Sichel says.

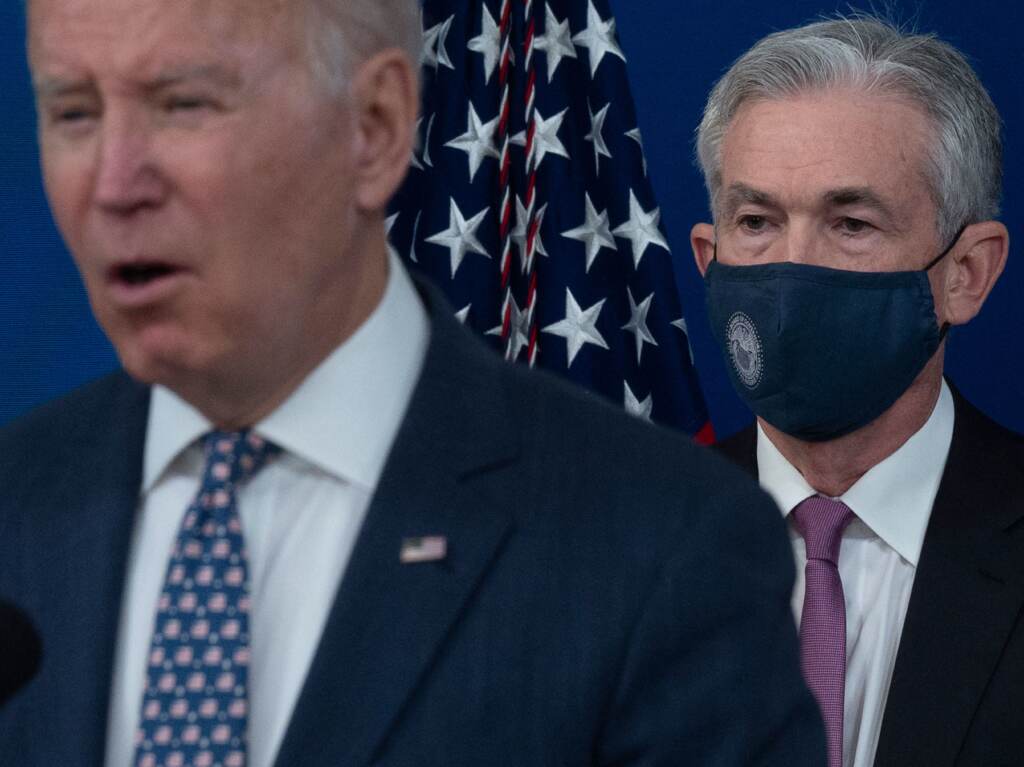

Biden, whose approval ratings have fallen as prices climb, calls fighting inflation his top domestic priority.

“I know that families all across America are hurting,” Biden said Tuesday. “I know you’ve got to be frustrated. I know. I can taste it.”

The president blamed pandemic-related supply chain snarls and the war in Ukraine as the leading causes of inflation.

While the administration has tried to offset price hikes with oil releases from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and other moves, Biden says the Federal Reserve has a primary role to play in bringing down inflation.

The Fed is fighting inflation

Chris Waller, who sits on the Fed’s governing board, agrees.

“Inflation’s too high and my job is to get it down,” Waller said Tuesday at the Economic Club of Minnesota. “We have to raise [interest] rates. We have to cool off demand and try to get inflation pressures down. If we get some help from supply chain resolutions, that’s fantastic, but I’m not counting on it.”

The Fed raised interest rates by half a percentage point last week and signaled that two more jumbo rate hikes are likely in June and July.

Waller and his Fed colleagues argue that the economy and job market are strong enough to weather a rise in interest rates without a sharp jump in unemployment.

But Waller concedes that if layoffs happen, they’re likely to hurt the same people who are already most affected by rising prices.

“We’re trying to lower the inflation tax on everybody, but there’s a small section of the society that may bear the brunt of that by losing their jobs,” Waller says. “There is no magical formula in a textbook that tells you how to do it. You kind of have to take your chances and see where it goes.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))