Fire-resistant is not fire-proof, California homeowners discover

A motorists on Highway 101 watches flames from the Thomas fire leap above the roadway north of Ventura, Calif., in December 2017. Hundreds of homes were destroyed in what was then California's most destructive wildfire. (Noah Berger/AP)

California’s building codes are not keeping up with the severe, wind-driven wildfiresthat are becoming the norm.

California’s building codes are not keeping up with the severe, wind-driven wildfires that are becoming the norm.

Ten years ago, the state passed strict new standards for homes built in high fire-risk areas.

But even homes built to those standards were destroyed in last year’s massive Thomas Fire. Now, those burned out homes are being rebuilt in the same places, under the same codes.

In the Ventura foothills of southern California, four of the nine homes on Andorra Lane burned down in the Thomas Fire. Almost no one expected it. After all, the homes were brand new. They were surrounded by dozens of other homes. And most importantly, they met the state’s building codes for areas at heightened risk of wildfires.

Nancy Bohman, who lives in one of the Andorra Lane homes that survived the fire, said she was, “totally shocked. Totally blown away, ’cause look,” she said, slapping the sturdy outside wall of her house. “It’s stucco and a concrete roof.”

There was at least one agency that suspected homes in this area could burn: CalFire.

Andorra Lane is tucked into a fold of the foothills above Ventura, and the entire nine-home subdivision is in a “very high fire hazard severity zone,” according to CalFire, the state fire agency.

That’s a technical term created by CalFire, and it applies to neighborhoods on the edge of undeveloped land, “the wildland urban interface” where severe wildfires are likely.

The term is important because, since 2008, all homes built in these zones have had to meet strict building codes designed to prevent them from catching on fire. They must have fire resistant roofs and siding; fine mesh screen on attic vents to keep embers out; decks and patios made of non-flammable material, and heat-resistant windows.

Built in 2016, the houses on Andorra Lane had all of those things. They were supposed to have a better chance of surviving a wildfire than older homes that didn’t have those protective features.

Always read the fine print

When the first residents of Andorra Lane moved into their houses in 2016 and 2017, few realized their homes were located in a risky place. But buried in their closing documents was a small disclosure, telling them they were moving into a “very high fire hazard severity zone.”

“We flipped through hundreds of pages, I’m sure nobody ever reads the fine print,” said Phil Azer, one of the four homeowners on Andorra Lane whose house was destroyed. “I think I was probably more concerned about earthquakes.”

His neighbors had similar experiences: only one recalled seeing the fine print.

“I don’t think [the real estate agent] ever actually said, ‘Hey, do you realize you’re on a flood or fire zone, or anything like that?'” said Bohman.

The developer, Williams Homes, declined to comment.

So why did the houses burn?

Ventura city Fire Marshal Joe Morelli thinks topography played a role.

The narrow valley that Andorra Lane sits in may have acted as a wind tunnel, funneling embers towards the houses.

“Really what we had was something like a blow torch going through our city,” Morelli said. “And even with the fire-resistant construction standards you can still have loss. They’re not fireproof standards.”

Researchers who study how houses burn down say it’s embers that are responsible for burning houses down, not walls of flame.

When embers land on ornamental mulch, pine needles built up at the base of a wall or wooden deck furniture, they smolder. And those little fires can eventually ignite the house itself, even a fire-resistant house, especially if no one is there to put them out, as is usually the case in an evacuation zone during a megafire where firefighting resources are stretched thin.

The current California wildland fire codes may also have weaknesses, according to Morelli. They don’t cover wooden sheds, carports, or backyard play structures, which can ignite, sending embers towards the house. Nor do they cover skylights that open outwards. And garage doors aren’t as fire-resistant as they could be, meaning embers can get sucked underneath them, igniting whatever is inside.

Being new, the houses on Andorra Lane were likely some of the most fire-resistant in Ventura. But many of the older houses that burned in the Thomas Fire also had some fire-resistant features.

According to CalFire data, 80 percent of houses destroyed in the Thomas Fire had fire-resistant exteriors. And 90 percent had fire-resistant roofs.

It’s where you build, not what you build

To fire ecologists like Alexandra Syphard with the Conservation Biology Institute, it’s becoming increasingly clear that houses built in risky places are impossible to fire-proof.

“You can make a big difference in increasing the potential safety of your house but you can’t guarantee that it’s not going to burn,” she said.

Her research has found that where you build your house, not what it’s made of, is the biggest factor in determining whether it will burn.

And approving new development is done by cities and counties, which often have a financial incentive to greenlight construction projects. The state tries to guide them to do the right thing, but “at the end of the day, it’s up to the local jurisdiction to protect their citizens,” said Pete Muñoa, CalFire’s deputy chief of land use planning.

He says it’s really only academics who are discussing giving the state more control over where houses are built in fire prone areas.

“They talk about that all the time,” he said. “‘They shouldn’t be building there, period,’ is what I’ve heard a few of the professors state. That’s easier said than done. Where do you put those folks? And how do you compensate them for that?”

In early October, workers were almost done framing Phil Azer’s replacement house on Andorra Lane. A small yellow sign in the front yard read, “Permits issued! Construction starting soon! Ventura strong!”

“Financially it made the most sense for us to rebuild,” Azer explained, because the insurance company would give him more money if he rebuilt than if he walked away and built a new house somewhere else.

Azer’s experience — rebuilding in the same place, to the same building codes, is quite common — a study published earlier this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found rates of home construction are higher in the footprint of wildfires than in surrounding areas.

“We are not changing our building patterns to become more fire resilient if we just put houses in the exact same places,” said Volker Radeloff, an ecologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the lead author of the study.

“They may not burn a year or two later, but 10 to 20 years later, there will enough fuel for the next fire.”

But city and state officials are reluctant to do anything that would increase the cost of new housing. Yolanda Bundy, the chief building official with the city of Ventura, said she’s just not focused on changing local building codes or overhauling land use planning at the moment.

“Right now, all the efforts are concentrated on helping people rebuild their homes, not to create more rules or regulations or more processes,” she told KPCC earlier this year.

The burned homes in “very high fire hazards severity zones” will be rebuilt according to the newest codes, and Bundy still considers that a big improvement since nearly all 777 of them were constructed before 2008.

Statewide, new building codes are adopted every three years. That means lessons learned from the Thomas Fire will not be incorporated until the next round of code changes.

“We’re constantly playing catch up,” said Muñoa. “We’re trying to be proactive to see how we can make homes more survivable by adding additional code requirements.”

But, he said, regulators also have to balance safety with cost. “Depending on the pushback we get from industry, we may or may not be successful in getting codes that we believe are going to be effective.”

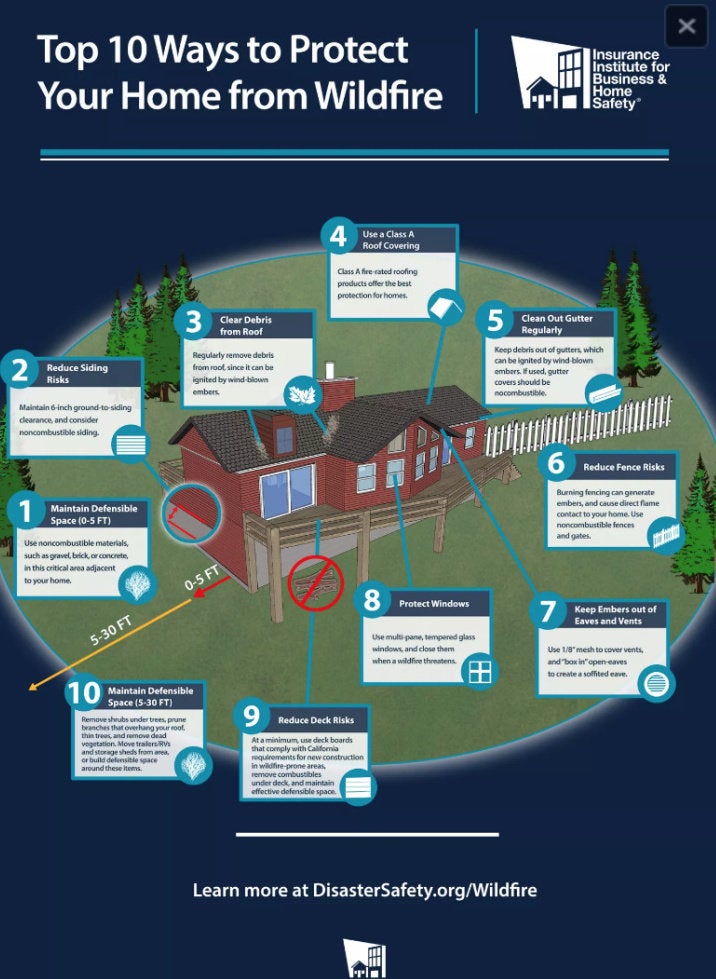

What you can do

So, what should you do if you live in a high fire risk area, or are rebuilding your house in one?

Focus on the area 30 feet around your house, says Tom Welle with the National Fire Protection Association.

The first five feet out from your foundation should be nearly bare, or only covered with non-flammable plants or landscaping. Beyond that, Welle says to “think about where leaves and debris just pile up because of wind. That’s where embers are going to go.”

Also, when a Red Flag warning is called, bring patio and deck furniture inside, and move things like propane tanks away from the house.

Keeping your house from igniting is really important, because according to Ventura Fire Marshal Morelli, nearly 90 percent of houses that ignite, even brand new houses, eventually burn down.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))