Eviction filings are up sharply as pandemic rental aid starts to run out

Eviction filings are rising even as rents spike and inflation cuts deeper into household budgets. (Getty Images)

Emergency rental aid has helped keep millions of people in their homes during the pandemic. But that federal program will start winding down this summer, when it expects to have allocated all of the $46 billion from Congress.

About half of that has been spent so far, and in some places programs are now running out of their share of the money and shutting down. That’s sending eviction filings up sharply, even as rents spike and inflation cuts deeper into household budgets.

In Plymouth, Minnesota, Wayne Meschke says getting eight months of federal rental aid was a huge relief. The 61-year-old works in hospitality as an executive recruiter, and depends on commissions. He says his company was devastated when Covid hit, and then he missed more work with a case of breakthrough Covid last fall. His kidneys and lungs have still not fully recovered, and exercise can be tough. His income is also still spotty.

“It’s like a wave,” he says. “There’ll be a month that it’s ok and then I’ll go three months that it’s not.”

But in January, Minnesota’s rental assistance program, RentHelpMN, ran out of money and stopped taking new applications. Meschke’s aid stopped in April, and soon he got an eviction notice. He plans to sell his car to help pay rent. And he’s reached out to family, and a religious nonprofit he once donated to, asking if they can help.

“If not,” he says, “I’ve got five adult kids. I may have to go live with one of them in their houses.”

Since Minnesota’s aid program shut down, eviction filings are way up. Programs have also shut down in a number of states, including California, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Texas.

“Our tenants are having to decide between buying food for their children or their elderly parents, or paying rent. And that’s a real tight squeeze,” says Dana Karni of Lone Star Legal Aid in Houston.

Texas, and Houston in particular, has actually been a model for the Treasury Department’s emergency rent relief program. Last year, when it was having a slow, rocky start in many places, Texas was able to get far more money out the door to struggling tenants. Because of that success, when funds ran out the Treasury Department re-allocated more money, part of an effort to shift it to where it’s most needed.

Legal aid groups in Houston and surrounding Harris County have also proactively reached out to help renters, sending attorneys to courthouses to offer assistance that can be crucial in avoiding eviction.

But not all landlords and property managers work with tenants to get that aid. Janie Mendoza is a single mother of six in Houston. She fell behind on rent when her kids were sick during the pandemic and she had to cut her work hours as a hostess. Mendoza says she applied for rental assistance — actually three times, as she found the process confusing.

“The one manager that was helping me from before, she was trying to do her best to provide whatever she could,” Mendoza says. “Once she left and another manager came in, it just turned everything upside down.”

Mendoza then got an eviction notice.

Some worry there will be a return not to normal, but to ‘worse’

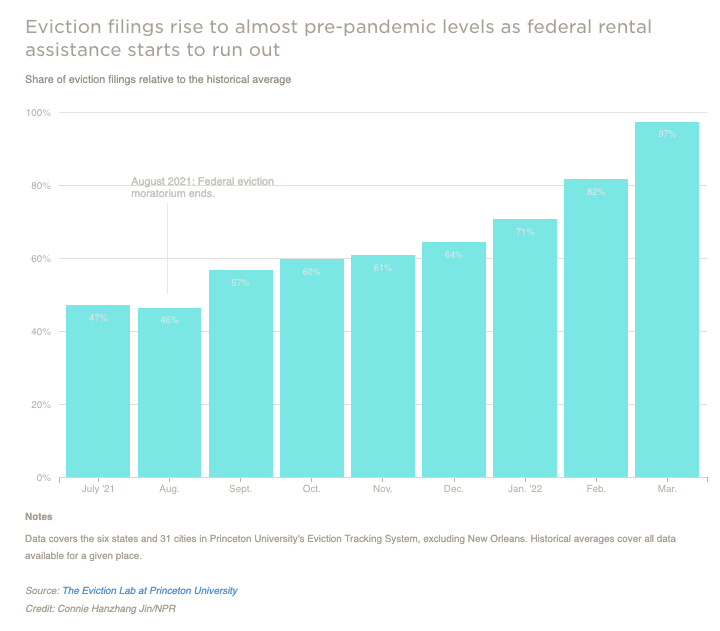

For much of the pandemic, a range of economic aid and restrictions on evictions kept eviction filings well below normal. Even after the national moratorium on evictions ended last August, rates rose slowly. Peter Hepburn tracks filings in six states and 31 cities for the Eviction Lab at Princeton University, and he saw a notable shift this spring. As rental aid programs started closing, eviction filings overall have reached nearly the same level as before the pandemic.

“There’s no limit on landlords’ ability to use the courts to evict people,” he says. “And there’s less incentive for them to try an alternative, because the money that was there — that could make them whole again, that could pay back rent — is no longer there in a lot of cases.”

Legal aid attorney Karni says even the extra rental assistance that’s been allocated for Houston is not nearly enough. She says right now, there’s an “outrageous” number of filings every week, and “I don’t think it’s going down, not only anytime soon but maybe ever again.”

Diane Yentel, who heads the National Low Income Housing Coalition, shares that concern that eviction filings may eventually stabilize at a level that is “worse” than before the pandemic, in part due to the rising cost of renting a home.

“The longer we go past the time the eviction protections or resources are gone,” she says, “the more we’re seeing in some of these cities, eviction filing rates reach 150%, 200% of pre-pandemic averages.”

Well before COVID-19, Yentel says, some 10 million of the lowest-income households paid at least half their income for monthly rent, and many far more than that. While some wages have risen during the pandemic, inflation is now eating into them and rental prices have climbed 17% over the past year, according to Redfin. They rose by a third in several cities in Florida, and a whopping 40% in Portland, Oregon.

Yentel says all this threatens to leave even more people “one financial shock” away from missing rent and facing possible eviction or even homelessness.

The affordable housing crisis needs long-term solutions

The end of rental aid hits landlords too, especially small ones with months of unpaid rent and bills, says Greg Brown of the National Apartment Association. And he says this moment comes as the country’s larger affordable housing crisis has only grown worse. Along with rising rents and inflation, supply chain problems are slowing badly needed new construction.

“It’s kind of amazing that all this has happened right around the same time,” he says, “and it’s a real tenuous situation, for both providers and developers and residents.”

Brown says housing is so tight, occupancy rates nationally have hit a record 97%. One association member recently told him he only has 8 vacancies out of 8,000 units.

Brown says this crisis needs a long term fix. After years of low production, the country is short millions of apartments and homes. He wants Congress to pass legislation to promote more multi-family housing, something Biden also included in his recent budget proposal.

Meanwhile, as federal rental aid runs out, the Biden administration wants more states and cities to step in. It’s urging them to follow the example of New York, which recently committed $800 million of its pandemic recovery money toward helping struggling renters stay in their homes. And on Monday, Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo praised California’s plan to use $7.4 billion of its relief money to build and preserve more affordable housing.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))