As the nation chants her name, Breonna Taylor’s family grieves a life ‘robbed’

Breonna Taylor poses with her car on Dec. 25, 2019. Her friends and family remember Taylor as a caring person who loved her job in health care and playing cards with her aunts. (Taylor Family)

Before she was a hashtag or a headline, before protesters around the country chanted her name, Breonna Taylor was a 26-year-old woman who played cards with her aunts and fell asleep watching movies with friends.

That changed on March 13, when police officers executing a no-knock warrant in the middle of the night killed her in her own apartment in Louisville, Ky.

Now, as protesters around the country have taken up her name in their call for racial justice and an end to police violence, Taylor’s friends and family remember the woman they knew and loved: someone who cared for others and loved singing, playing games, cooking, checking up on friends.

Before the early morning raid in March, Breonna Taylor was a first responder who loved to sneak in a nap before her next shift. She would have turned 27 on June 5.

Known as “Bre” to her friends and family, Taylor moved from Michigan to Louisville when she was a teenager. Much of her large, tight-knit extended family moved around the same time.

One aunt, Bianca Austin, called Taylor her “mini me.” An uncle, Tyrone Bell, called her “Breezy.”

“She was cool, a cool cat,” says another aunt, Tahasha Holloway.

The family regularly spent time together, and Taylor often proposed a round of her favorite card games, Phase 10 and Skip-Bo.

The work schedule of an EMT could be grueling; it was especially so in early March, as worries about coronavirus spread.

But those who knew her say Taylor welcomed the opportunity to give back and to make a difference in someone’s life.

Friends and family agree that Taylor was attracted to a career in health care because she cared about people. In a Facebook post Taylor made as her uncle recovered from a stroke last year, she wrote:

Working in health care is so rewarding. It makes me feel so happy when I know I’ve made a difference in someone else’s life. I’m so appreciative of all the staff that has helped my uncle throughout this difficult time and those that will continue to make a difference in his life.

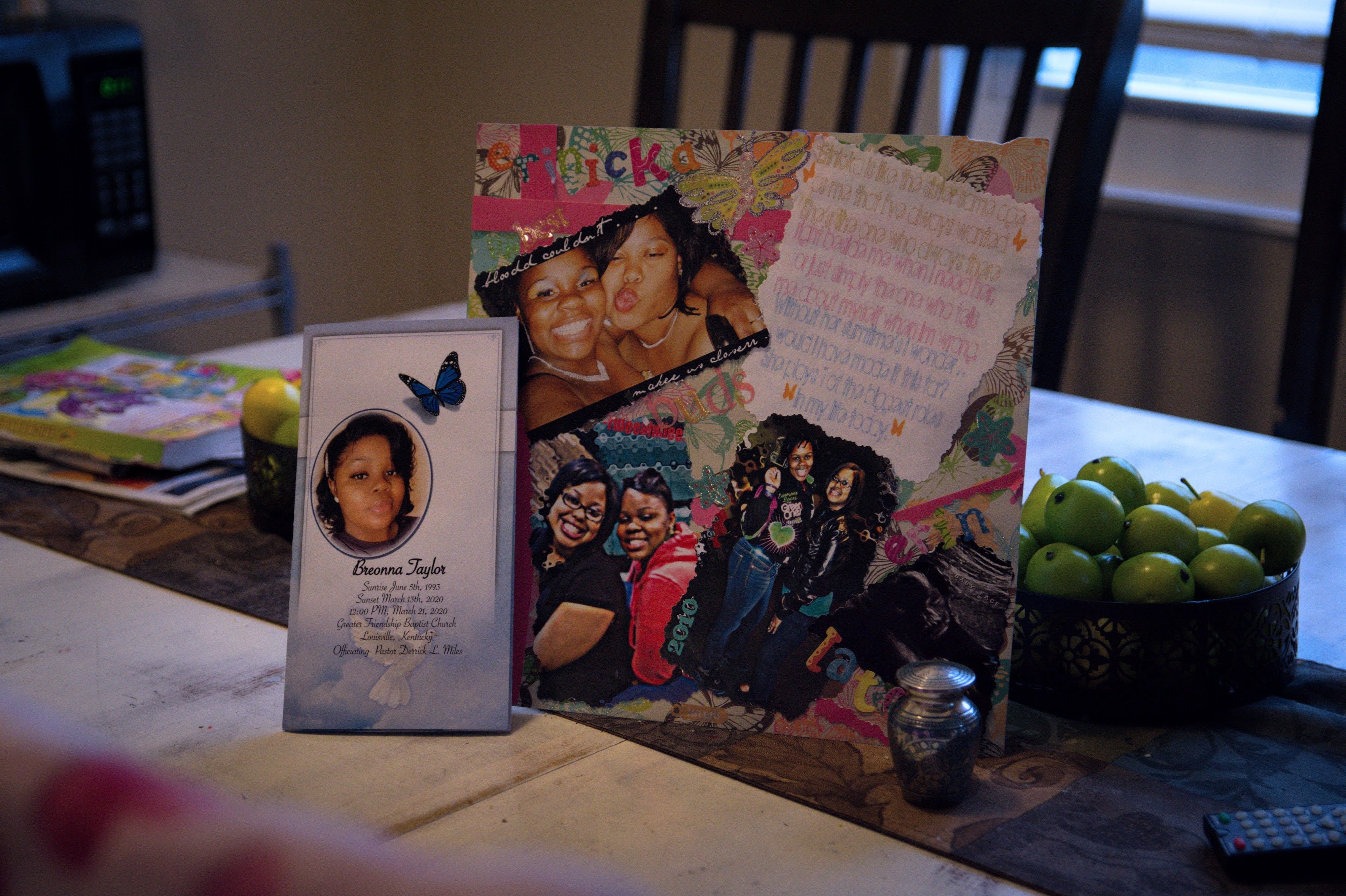

She attended Western High School in Louisville, where she met and befriended Erinicka Hunter and Shatanis Vaughn — they were, in their words, “the three amigos.”

Like many 20-somethings, Hunter and Taylor drifted apart at times in the years after high school. But Hunter remembers rekindling their friendship last year after Hunter underwent brain surgery. She was recovering in the hospital when Taylor came to visit.

“I’m like, ‘Why did we fall out? I don’t understand.’ And she was like, “It doesn’t matter, Nick. We together again. Don’t worry about that. I love you. Just know that,'” remembers Hunter. “It’s not right. We was robbed.”

Breonna Taylor’s death in March came as a shock to those who knew her.

She and her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, were at home in her apartment, when a team of plainclothes Louisville police officers arrived to execute a no-knock warrant early in the morning of March 13. According to her family’s lawyers, the subject of the investigation was not Taylor, but a man she had dated previously who had once sent a package to her apartment.

When police broke into the apartment, Walker thought they were being robbed, Taylor’s lawyers say. A licensed gun owner, he grabbed his weapon and shot an officer in the leg. The officers returned fire, shooting dozens of times, killing Taylor, according to the family’s wrongful death lawsuit. Police arrested Walker, and he was charged with attempted murder of a police officer. Those charges have since been dropped.

“Even in being a prosecutor, I’d never quite seen that many bullets in one apartment,” says Lonita Baker, a personal injury attorney representing Taylor’s family. In addition to the lawsuit, the family is also seeking departmental policy changes on body cameras and no-knock warrants.

The earliest news stories covering her death didn’t mention her name at all, instead focusing on an injury to a police officer and referring to Taylor and Walker as “suspects.”

Breonna Taylor’s family said they felt anger when reading those early stories.

“I probably said more cuss words in that little time than I said throughout my whole life,” says Bell, her uncle. “Angry is an understatement.”

Her aunt Bianca Austin believes that, along with the burgeoning outbreak of coronavirus, that this early narrative of Taylor as a “suspect” is why the family had difficulty finding funeral service providers.

Now, two months later, the whole nation knows Breonna Taylor’s story. Thousands of protesters across the country demonstrating against police violence chant her name along with George Floyd’s. In Louisville, it’s Taylor who takes center stage – literally, with a mural of her smiling face drawn in chalk in downton’s Jefferson Square Park.

The family says it lifts them up to know her story is being heard — but also makes it harder to grieve.

“Every time I see her, or someone says her name, I cry. I break down,” says Shatanis Vaughn, Taylor’s high school friend. “They really supporting you [Taylor] now. Everybody knows your story. You’re going to be heard, finally.”

Austin, her aunt, says the family is “grateful that her name is where she should be.”

“But we don’t want this at all,” she continues. “We want her back. I would rather just go back in time.”

For what would have been Taylor’s 27th birthday, friends and family have planned a public celebration of her life on Saturday in downtown Louisville. They plan to release balloons and butterflies, and are expecting a large crowd.

“I’m praying to God,” says Austin. “We need real change in America. I’ve got to still raise a little black boy here in the world we live in. … Nobody’s safe. If this can happen to Breonna, it can happen to anybody.”

“She always said that she would be a legend,” friend Erinicka Hunter says. “I just never imagined it would be like this.”

Sarah Handel edited the audio story. Maureen Pao edited the web story.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))