Hope, love and basketball: Summer at North Philly’s Hank Gathers Rec Center

A summer at the Hank Gathers Rec Center will tell you everything about North Philadelphia that the headlines leave out.

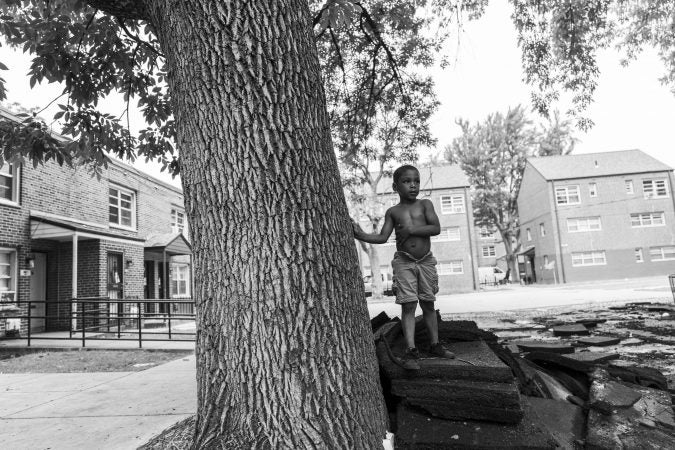

It’s the last day of school in Philadelphia. Summer at the Hank Gathers Recreation Center has begun, the outside basketball courts packed with children, a feeling of wide-open possibility in the air.

“I have freedom. I’m free to do whatever I want,” said Jahkare, 16. “Play sports, like girls.”

Bionna, 16, dribbles a basketball non-stop as she talks.

“No more school for the summer….sleep ‘til like 12, probably go out, play ball,” she said, recounting what she expects in a typical day.

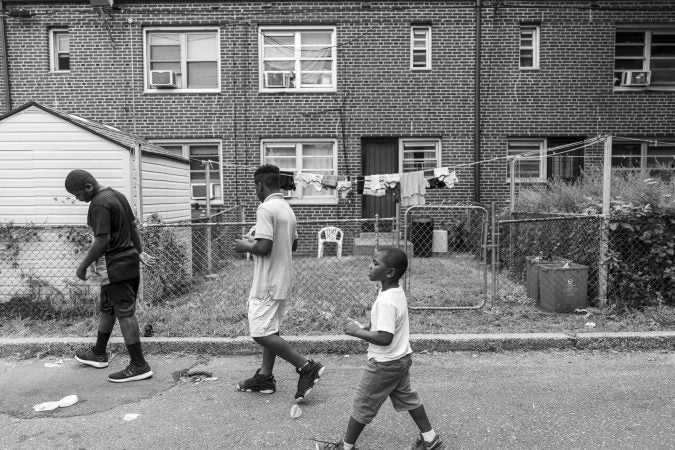

Hank Gathers is at 25th and Diamond Streets, in a part of North Philadelphia particularly plagued by deep poverty and violence. Many of the kids who come here live in the surrounding public housing.

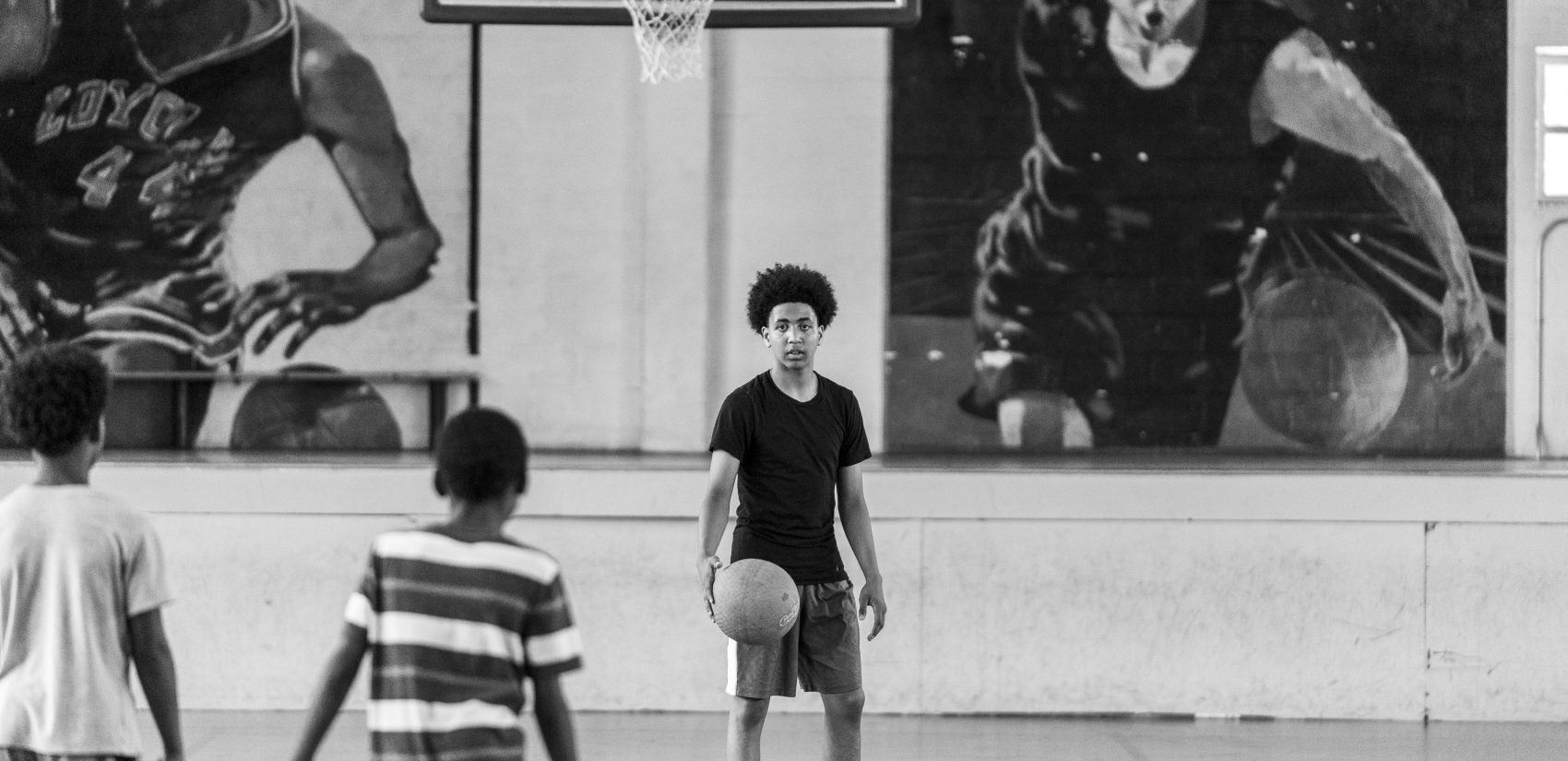

And during the summer especially, basketball is a way of life.

The games are intense.

Trash talk runs like a river.

And with some kids you can see how the game brings them to life, energizes them, gives them the hope that maybe — just maybe — if they work hard enough, basketball will take them somewhere else.

“Life’s about staying humble, and doing what you gotta do to sacrifice and live,” said Shawn, 15. “Around here, it’s hard. It’s either you play ball, or…”

Or what?

Shawn trailed off, didn’t want to say.

“If you play a sport, get a scholarship…” he said, a distant look coming to his eyes.

It was as if he could see the outlines of a vision he had dreamed many times before. In a flash, though, he redirected himself, snapped back to the hot June blacktop of the present.

“But it’s the last day of school, man,” he said. “We ain’t got no more school. Let’s get it.”

This story was produced as part of WHYY’s Schooled podcast. You can listen above, or subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

School.

Lots of time and energy and money are poured into this idea. In most cases, it’s six and a half hours a day, 180 times a year.

What happens in those combined 1,200 hours consumes much of our attention. What are students learning? Is the school doing a good job? What’s happening big picture with politics and policy?

Especially in our most distressed communities, there’s a hope that if everything aligns, if things work right, school will be the great equalizer — the crucial piece that could make or break someone’s life.

But what about all the time students spend outside of the classroom? Those other, 7,000-some hours?

What are they learning? What are they doing? Who’s there for them?

We were curious.

So we spent the summer of 2018 going to Hank Gathers to find out — to tell stories about those other hours.

Most stories you come across about this part of North Philadelphia are about crime. A shooting on the ‘x-hundred’ block of something. A young man dead on the 11 o’clock news. A crying neighbor on a porch. A statement from a weary detective. An anchor in a suit and tie speaking in grave tones.

And it’s true. There is a lot of crime in the neighborhoods that surround Hank Gathers. The fear of gun violence and death is like a constant backdrop.

It’s hard to find someone in the neighborhood who doesn’t bring it up.

“There’s always a lot of trouble on Diamond Street. When I be in my room, I can hear the sirens and stuff. Somebody else got shot or something. It’s always something,” Bionna, 16.

“Lot of shootings for no reason. Too many people dying and I don’t want to be one of them,” Stephon, 15.

“I hate people dying, man. There’s a lot of people dying in my ‘hood,” Shawn, 15.

“I’m worried if I’m going to make it or not — make it past 20, 21. It’s rough out here, man. I’ve seen a lot of good people turn into bad people,” Daishon, 15.

“Really happy to see 23 the way so many people are dying nowadays…I could have been at the wrong place at the wrong time,” Davonne Glover, 23.

But as real as these fears are, and as much as shootings drive headlines, this isn’t the whole picture.

This story is about those other moments, about the people still here after the breaking news van drives away.

***

The first time we met Shawn, on the last day of school, we could tell he was a leader.

He was with a group of other kids on the outdoor basketball courts who asked why we were there. Most of the kids at Gathers are black, and a couple of 30-something-year-old white guys with microphones stick out.

We told them we were doing a story on what happens after the last day of school.

“We playing ball. Fucking bitches. Getting money,” said one of the teens.

Shawn stepped in to wave away the bravado.

“We’re not,” he said. “Sir, we’re not.”

Shawn lives with his mom and three siblings at Raymond Rosen Manor, a low-rise public housing complex a block from the rec center. He’s the oldest kid in the family, and has the presence of someone who’s accepted the idea that he’s responsible for more than just himself.

On the basketball court it can come across as confidence, maybe even cockiness.

“I can tell I can beat you,” he scoffed. “I can tell by the way you walk. You gotta have a little walk when you play ball.”

Shawn is lean and agile with a halo of puffy hair. He plays the game with focus and intensity, like he knows the stakes are higher than the outcome of any one game.

Talk to him off court, and there’s something deeper, more tender. He has the instincts of a protector, someone who, without hesitation, is there for friends and family.

Any time we interviewed one of his close friends, Shawn made sure he was there to chaperone.

“I want to listen to you,” he said as we interviewed his friend, Greg. “I don’t want you saying nothing dumb.”

Shawn and Greg call each other brothers.

“We’re not literally brothers,” said Greg. “We do what brothers do, though. Like, I’m not going to let nobody say nothing to him wrong.”

“We both do the same things,” said Shawn. “He’s actually smart. You wouldn’t think he’s smart, but he’s smart.”

“He’s a good person to hang around. He’s a positive person,” said Greg. “He’s not like everybody, trying to hang on the corner. He wants to play ball and he’s not going to let anybody stop him.”

When you talk to Shawn about motivation, it all comes back to his mom.

“I wouldn’t play ball if it wasn’t for my mom. There wouldn’t be no point. I just want to leave — get my mom out the ‘hood,” said Shawn. “[Otherwise], I probably would be out here doing what everybody else does. I’d probably be a bad little kid. Drunk. In these streets. Probably sell drugs when I get older and all that. But I wouldn’t play ball. There would be no point.”

Shawn’s mom, Shanika, had her son when she was 15, Shawn’s age now.

“I’ve never doubted my son,” she said. “I’m glad I had him, because he taught me to mature myself as a young lady. So, if it wasn’t for him, lord knows where I would be.”

Shanika works as a support staffer in Philly public schools, and is training to become a certified nursing assistant. She dreams of moving to Virginia, but hopes a new gig will allow her at least to afford rent outside the projects — maybe Northeast Philadelphia.

“I put a roof over my kids’ head. They’re well fed. They have clean clothes on their body,” she said. “So at the end of the day, my kids are all that matter — nothing else, you know? I feel like I laid down, opened my legs and had those kids. I got to take care of them.”

Shawn’s dad was in jail for much of his life. He’s out now, but not in the picture.

“Every child needs their father in their life,” said Shanika, “but sometimes you can’t make a man be a man.”

Shawn met with his dad recently, but has no plans to continue.

“I just don’t need the man. I didn’t need him my whole life,” said Shawn. “He’s going to need me.”

Shanika hopes her son can learn from her work ethic.

“I just want him to get out of the neighborhood and do bigger and better. I want him to go to college,” she said. “I want him to be big and do better.”

***

Like many of his friends, Shawn thinks basketball could be the ticket out. And as unlikely as that may seem on a pure statistical basis, at the Hank Gathers Rec Center, it’s not completely out of the question.

Kyle Lowry. Marcus and Markieff Morris. Dawn Staley. Hank Gathers.

Those are some big names in the world of basketball.

Lowry is an NBA All-Star who just won a championship with the Toronto Raptors.

The Morris twins are league veterans.

Dawn Staley is a three time Olympic gold medalist on the women’s team and an NCAA champion coach.

Hank Gathers, the rec center’s namesake, was a top prospect who died suddenly on the court of a heart condition in college in 1990.

All of them grew up here playing on these same courts where Shawn and his friends play.

And to this day, the rec center has one of the most well-known basketball programs in the city.

“Hank Gathers — it’s one of the greatest recs we have,” Davonne Glover, 23.

“This is the mecca,” George Patterson.

“This is where everybody meets in the middle,” Curtis Pannell, 28

“If you think you’ve got game, you gotta go through the Hank center,” Mark.

“I didn’t have role models growing up. But playing basketball, a lot of coaches changed my life at Hank Gathers,” Abdul King, 25.

“I wouldn’t want to play or grow up nowhere else than around this gym right here,” Eddie “Bisil” Savage, 49.

***

There’s an informal check-in system at Gathers.

Kids walk in the double doors, up a short flight of stairs. They go halfway through a small entry area with concrete walls — covered in every type of sports poster imaginable. Turn right into a carpeted room and the TV is almost always blaring: CNN. Law and Order. Local news.

There, kids find Jimmy Richardson and George Major in a pair of ragged armchairs.

The ritual is as simple as it is charming.

The kids walk up, shake hands. For younger kids, it’s a traditional handshake. Older kids, more of a slap and clasp.

It’s like the Gathers’ version of morning attendance. Walk in. Shake hands.

It’s a little gesture that tells you a lot about the rec center. The world outside may be unpredictable. But not here. In here, there is order.

“It’s a different society up here,” said George Major. “Everything’s different up here. ‘Cause it’s rules in here.”

Major sports a shaved head and bushy, graying beard. His eyes — wide and intense — give his gruff lectures extra weight.

Like a lot of people around here, Major’s story intersects with the world of basketball. He helped raise Marcus and Markieff Morris.

But Major likes to talk about life before the NBA twins, when he was growing up in this neighborhood. He was one of 13 kids, he says, born to a single mother.

“Sometimes I would come in the house — wasn’t no food at the table,” he said. “And I would go back outside and take something.”

Stealing led to other crimes. Hustling. Drugs. And eventually, jail. It’s a familiar story: poor kid, wrong crowd.

Major turned his life around, and tells just about any kid who will listen. It’s part of the George Major experience. Real talk.

“I’m a tell ‘em about history,” he said. “About these streets.”

Jimmy Richardson is the yin to Major’s yang. They say a lot of the same things, but Richardson’s tone is more dean of students than dean of discipline.

“I tell ‘em half y’all gonna make it and half y’all not,” he said. “And that’s the reality of it. Half y’all gonna listen. And half y’all not. So what do you wanna do?”

Richardson’s cousin, Jerome “Pooh” Richardson, had a long career in the NBA and played alongside Jimmy on the 1984 Benjamin Franklin High School city championship team. Jimmy went on to play college ball in North Carolina and returned home after graduation. Raised by his mom in public housing, he always aspired to the kind of life he saw modeled by neighbors and mentors.

“I was around a lot of people who done 30 years on one job and I was fascinated about that,” he said. “I thought that was stability. I thought that was a goal.”

Richardson started working at Gathers in 1991 and runs the basketball program with Major. They spend much of their days shuffling between the television room and the indoor gym, where there’s a big, bright basketball court with blue floors and murals of the center’s famous alum on its walls.

On Saturdays, they run scrimmages. During the school year, they organize league games. Weekday afternoons are set aside for informal coaching and training sessions — open to kids who want extra attention.

The duo has been around for a long time. They know the kids. They know moms and dads. When a boisterous young player bounces in the door on the first day of summer basketball camp, Richardson shoots him a playful warning.

“I got you,” he yells. “Your grandma told me what I gotta do with you.”

Gathers is distinctively unlike school. The rules are more like customs. It’s a place built on intimacy and rhythms instead of formality and bells — a very different experience for kids compared to the elementary school across the street.

“We got a team where they feel love,” said Richardson. “Over at the school, over at William Dick, it’s kinda rough over there. What I’m hearing is that they’re running over the teachers. But, when they come over here, they can’t run over our staff.”

When kids do get out of line, the line of last defense isn’t usually Richardson or Major.

It’s Aunt Cheryl, the Gathers matriarch.

Her name is Cheryl Hardy, but you could go an entire summer without hearing it.

Aunt Cheryl, though? That name is like sonic wallpaper.

Aunt Cheryl, where’s the pizza money?

Aunt Cheryl, he spit water on me.

Aunt Cheryl, I’m here to register my son.

Aunt Cheryl…Aunt Cheryl…Aunt Cheryl.

“My whole scenario is about family,” she said. “Everybody’s cousins. And that’s how we always been. So they all call me Aunt Cheryl.”

Aunt Cheryl has been at Gathers longer than anybody — she grew up playing here. For decades she was a middle school teacher in the city who ran the day camp during the summer. She retired from her teaching gig, but stuck with Gathers.

“She keeps it going. She keeps it running,” said Kareema Hardy, Cheryl’s daughter who also works at Gathers. “The parents bring their kids back here because of her.”

Aunt Cheryl spends most of her day seated behind her desk or on a plastic chair in the entryway, like a latter-day Buddha with braids. People approach with questions or conflicts, and she dispenses whatever wisdom or directive the situation requires.

Her philosophy on how to treat kids boils down to two words: don’t holler.

“I know I wouldn’t want nobody hollering at me,” she said. “So I treat them the same way I treat my own kids. ‘Cause they are my kids.”

Almost every adult at Gathers mentioned some version of that thought. What separated Gathers from the world beyond, they said, was the absence of hollering.

“Why not give them a hug? Give them some love,” said Jimmy Richardson. “That’s where it’s at.”

There’s probably some trace of a buzzword in here — de-escalation, trauma-informed care, social-emotional learning. But the Gathers staff predate the buzzwords. For them, it’s common sense. You need to calm kids down.

Wailing kids seem to freeze in Aunt Cheryl’s presence, and then melt when she starts talking.

“We alright now?” she asked a young boy as he wiped away tears of rage. “And when things happen what you gonna do? Just sit and think first, right? Before you react, right?”

Aunt Cheryl spent a lot of her teaching years as a school disciplinarian. But it didn’t make her tough, at least not in the way you might imagine.

“When you come in here, I’ll tell you good morning,” she said. “I’ll give you a smile. If you have a problem, make sure you come and see Aunt Cheryl. We can talk about anything.”

Her style permeates everything about the center and its mission. She wants the place to feel like a refuge, so she can reach kids that aren’t yet part of the Gathers family.

“We try to get those kids that nobody else wants,” she said.

When kids do come, they find a place of joy, a world built by trusted guardians who have stood the test of time.

“They’ll help you with anything you ask for,” said Stephon, 15.

For Cheryl Hardy, George Major, and Jimmy Richardson — it starts at the door. A handshake. A hello. A gesture that separates Gathers from the streets beyond.

Of course, as soon as you start theorizing about these things with Aunt Cheryl, she’s usually called on to be Aunt Cheryl again.

A kid approaches with a gripe. Another hallway chat begins. Basketballs thunder in the other room.

And that door to the outside world swings open and shut.

Open and shut.

***

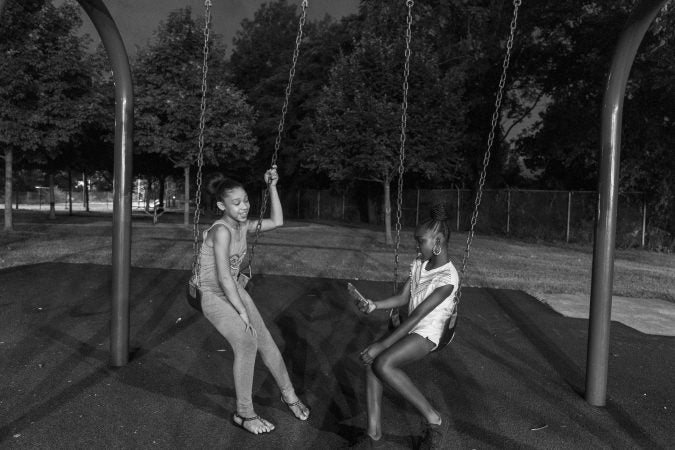

It’s mid-July. A Friday night at Hank Gathers, after 9 o’clock.

By this time, the rec center staffers are gone.

Eleven-year-old James is one of a few dozen kids running the outside courts.

— I’m just balling out tonight. I got some extra free time. I was supposed to be in at nine.

— How did you earn the extra free time?

— Being good, doing my chores and studying.

Kah-eem, 14, lingers by the bleachers. He says he was expelled from William Dick for fighting in 4th grade.

“People just think they can get the best of you and they pick on you,” he said. “Then you have to — you may not want to, but you’re going to have to fight.”

He says he’s more mature now. His father asked him to “straighten up” after he got in trouble.

“If you do meet me when I’m 20, in the future, when I’m older, I hope that I’m doing something positive,” Kah-eem said. “Well, I’m not going to hope. I’m going to try to do my best and try hard to make my family proud.”

Even without formal staffers, mentors are there. Older guys shoot around, mix in with the kids, give them pointers on their game.

Chris Robinson, 32, played alongside James. Just a few months before, he finished a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts from Penn State Brandywine.

“It’s an unbelievable feeling,” he said. “I still can’t believe I did it, but it was a long process.”

Most of his career has been in restaurants. He hung on to get his bachelor’s with the hope it would bring better opportunity.

“Just looking for a good job. I gotta pay off a lot of loans,” he said. “So that’s my first priority.”

There seems to be an unspoken rule in the neighborhood that Gathers should be a safe space, even on the outdoor courts. Most of the kids there are there to play, or to socialize. The adults that come, respect the kids.

You don’t see people selling drugs. You don’t see guys hanging out drunk or high. You don’t see violence. A block or two away, yes — but not at Gathers.

“Older guys will step up, and say something, ‘No, don’t do it out here. There’s kids out here.’ It’s like a safe zone,” said David Smith, 58. “There ain’t many in North Philly, but this is one of them.”

Smith brings his grandkids to the playground before his nightshift cleaning the butcher’s room at a supermarket. In the 1980s and early 1990s he ran a PCP operation before doing a decade in federal prison.

“Life: you gotta take the good days with the bad days — and all the rest — and just be thankful,” he said. “Be thankful for the small things. If you have your health and your freedom, you got a chance.”

If he could go back and do it again, Smith says he would have joined the army after graduating from Ben Franklin High School. Now, he sees people making the same mistakes he made, but says he knows enough not to interfere.

“You can’t tell people when they’re living their life,” he said. “They know. Life is going to be their teacher, not me — life will. They’ll find out the hard way, if they’re lucky, if they survive.”

Occasionally a fleet of four-wheelers and dirt-bikes rips down Diamond Street and puts a tinge of chaos in the air.

But for the most part, when the lights are on at the playground, the kids are free to dial into their game — free to forget whatever fear or dread or worry that lurks beyond the boundaries of Hank Gathers.

But then comes that moment. Every night you know it’s coming, but every night it takes you by surprise.

You know it’s getting late, but you haven’t checked the time. And all of a sudden — it’s 10:15 and the lights go out.

The kids, caught up in their games, bellow in shock as darkness hits without warning.

“Once we see the lights out, everybody just leaves the park,” said Nyon, 15.

Like Shawn, Nyon is a counselor at Aunt Cheryl’s summer camp during the day — a die-hard regular on the courts at night.

— Now what?

— I walk around

On this night, as the kids are leaving, a house across the street begins blaring music, loud enough for the entire neighborhood to hear.

Kah-eem takes off across Diamond Street on a bicycle, his friend Shailek on the back pegs.

Shawn, sweating through his shirt from the game, looks down the block that’s pulsating music as he starts towards home.

“Can’t do nothing about it,” he said. “They do something about it, there’s going to be a commotion. I don’t know what they can do about that.”

In other words, you pick your battles. Put stock in the wisdom of making it back to your bed at night safe. Know that the courts will again be bright and open tomorrow.

***

July in Philadelphia gets hot and humid — often oppressively so.

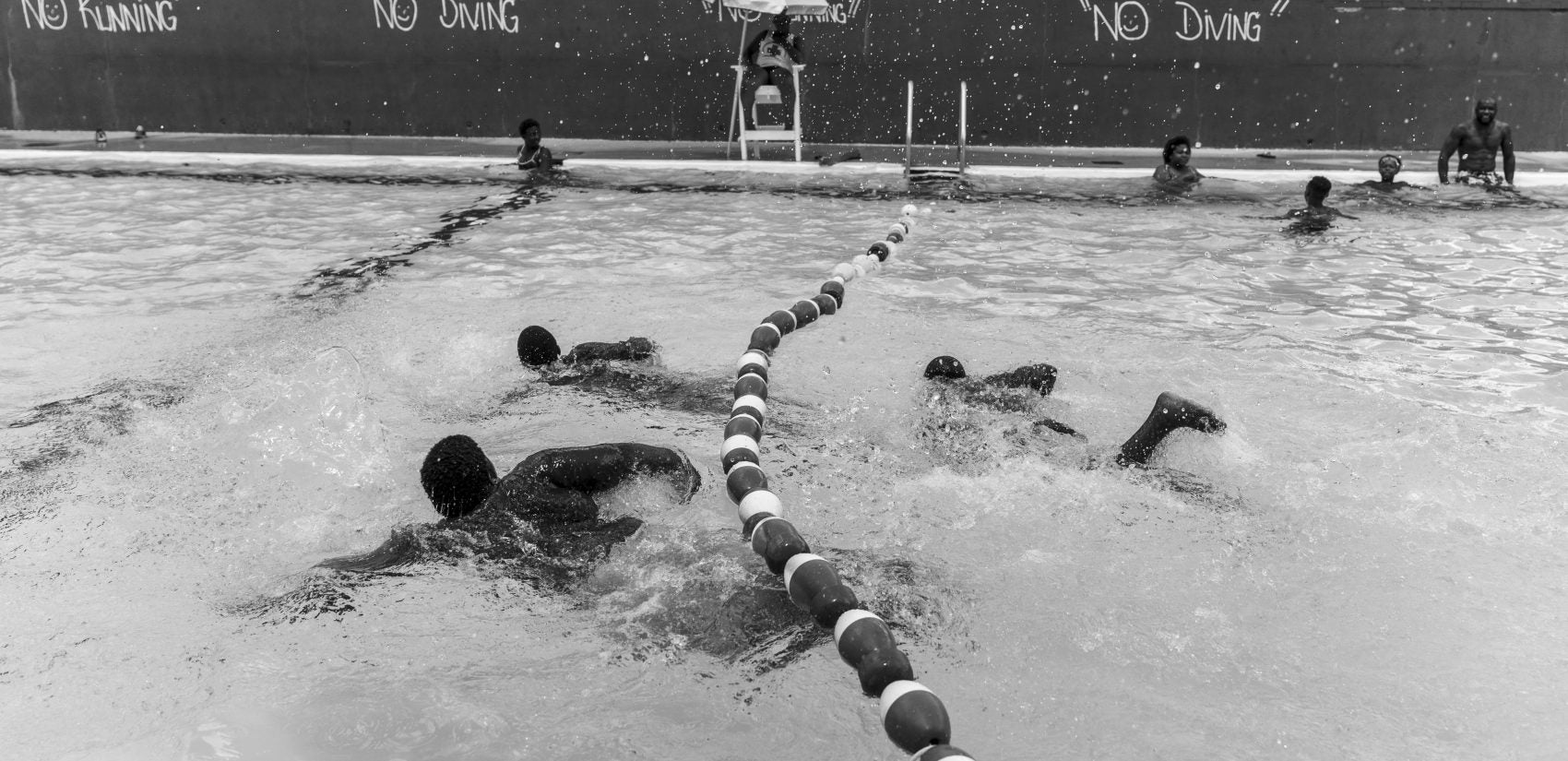

So as much as the scene at Gathers is about basketball, it’s also about the pool.

“It’s been really hot lately. In the 90s — 95. When we have a heatwave, that means the pool is open all day to the public swim,” said Howard Bolden, aviators, sweaty tank top, whistle hanging from his neck.

Bolden, 23, the head lifeguard at Gathers, is a neighborhood success story. He was a good swimmer in high school. Went to college at West Virginia. And was about to start his Master’s in sports administration at Georgetown.

— My tattoos tell my story, my history.

— I have the Philadelphia skyline on my back.

— I have West Virginia, WV, on my back.

— I have tattoos of my dad, who I lost when I was in high school, freshman year.

— I have my mom’s name on my chest, she raised me, made me who I am today. Taught me a lot of things, how to be mature, how to handle situations.

— I have, ‘Only the strong survive.’ I feel my struggle is making me survive. That’s the reason I’m here, looking to go further on in my career.

— I have a ‘Cry now, laugh later’ tattoo. I feel as though you can’t show your emotions all the time. You can’t show that you are down and out, that your crying about something, because people will take advantage. So you see me smiling, but it’s much more deeper than just a smile.

Bolden is the coach of the Gathers swim team. On this day, they have a meet at another rec center pool a few miles away.

As they gear up to go, a group of 8-and-9-year-olds on the squad hang out by the pool entrance.

— All my summer I came to this pool.

— Me too.

— Me too.

— What do you do when you’re not here?

— Play my game, Fortnite.

— It’s the newest game out.

— It’s fun, everybody plays it.

— What do you want to be when you grow up?

— A construction worker. And a scuba diver.

— Who do you like here who works at this rec center the most?

— Howard.

— He plays with us in the pool. Sometimes he throws us in.

A group of older kids show up, including Greg, Shawn’s friend.

— I’m from the trenches of Diamond Street. That means I came from the mud, the trenches.

— We came from the bottom, now we at the top, you hear me?

— We ain’t at the top yet, chill.

— Yeah, you tripping. I’m still in the mud right now.

When we get to the swim meet, the Gathers kids are rowdy. They’re now in a neighborhood that’s a bit fancier, on a pool deck that’s more manicured.

Gathers’ reputation is grittier. And the kids come in talking trash to live up to the name.

— I didn’t even know you could kick your feet.

— Ya’ll corny. They can’t beat us.

— Have you ever seen me swim? Oh, alright then.

Bolden shrugs it off. It’s hot, but nothing a dip in the pool won’t cool off.

***

One of the kids at the pool that day is Qu-ran, someone who floated in an out of the Gathers universe through the summer.

He was 13 and new to the neighborhood, but dove toward the microphone on the first day of summer.

“I go to Camelot,” he blurted out.

“You go to Camelot,” another kid asked. “Stupid.”

“Who stupid? Me?”

Qu-ran is not stupid. He did say he went to an alternative school in Philadelphia for kids with behavioral issues. And he quickly explained why.

“I pushed a teacher,” he said, sheepishly. “Yeah, I got expelled.”

Qu-ran spent the summer living with cousins in the James Weldon Johnson Homes, public housing a couple blocks from Gathers.

He had that strange jumble of physical traits that often comes with early adolescence: a deep, husky voice combined with a trace of baby fat in his cheeks.

And all of it set against a sly, disarming smile that he deployed regularly to ease conflict.

Qu-ran wasn’t a camp kid or counselor. He was one of many kids on the fringe. The adults at Gathers knew him, but he hadn’t been around long enough to be fully in the fold.

We wanted to understand life through his eyes. So, we spent a day with him as he traversed the neighborhood, looping through the world of North Philadelphia beyond Gathers’ gate.

***

It’s early August and insects buzz through the steamy morning heat. Qu-ran wakes around nine and heads to a morning basketball practice at Gathers.

At noon, practice ends and he turns back to the Johnson homes. Rumors have been flying about a pizza party in the basement of a housing project building.

Qu-ran’s hungry, so he clambers down the steps and yanks open a metal door. A woman stands in the entryway.

“Where y’all going,” she barks. “Not in here.”

“I thought y’all had a pizza party,” Qu-ran says.

She shakes her head. They only have enough pizza for the kids who hang out regularly at this site, which is run by the Boys and Girls Club.

Qu-ran sulks back to the street, but the rejection doesn’t linger. He isn’t wired that way.

Qu-ran’s only lived in the neighborhood for a few months, but he bounces around like he’s the mayor. Or at least a town crier. Almost every passerby gets a cheery hello, like something out of Mayberry.

— Sup, Anajah!

— Sup, Gramps!

— Hey, Rhino!

— Hey, Randy!

Qu-ran used to lived in another part of North Philly, he says, before he moved in with his cousins.

“You wanna hear some real shit,” he says. “I live with my aunt ‘cause my mom’s house got burned down.”

Qu-ran explains his mom needed to look for a house and she wanted him somewhere safe while she searched. These explanations are punctuated — even interrupted — by more greetings, and the occasional attempt at courtship.

— Hey, how you doin? You wanna get interviewed with me? I make money. $10,000 dollars an hour. Y’all could be a gold digger — psych.

Qu-ran collapses into laughter at his own joke, something he does regularly to break tension.

It quickly becomes clear that Qu-ran has nothing to do and nowhere to be. He and a group of friends begin to wander.

Cement walkways weave together the series of two-story, red-brick apartment buildings that make up the James Weldon Johnson Homes. Courtyards — in various states of repair and cleanliness — fill the gaps. And there’s a constant carousel of children skittering across lawns and disappearing into the rowhome-lined streets that surround the complex.

The other main public housing near Gathers is Raymond Rosen Manor, distinguished by its perimeter fences and gabled roofs. The project had once been the Raymond Rosen Homes, a clump of high-rise towers felled by Dynamite in 1995, driving thousands of families from the neighborhood.

A similar fate came in 2016 to the nearby Norman Blumberg Towers.

Longtime staffers at Gathers speak of these towers both painfully and wistfully. They were epicenters of the crack-cocaine epidemic in the 1980s and 90s — a time when Philadelphia’s murder rate surged to heights unseen in recent decades.

But the volume of people in the area back then made the basketball competition fierce, and old-timers grow nostalgic telling the legend of Friday night games in gyms stuffed to the gills with spectators.

These days, towers down, the neighborhood remains a pocket of deep poverty as gentrification encroaches upon North Philly. On the other side of Ridge Avenue, you see new construction in Brewerytown. Towards Broad Street, development in Francisville and around Temple University has been rapid.

Even Strawberry Mansion — cut off from Gathers by a noisy commercial railway running behind the center — has seen signs of a more prosperous future.

But those aren’t the neighborhoods Qu-ran roams. His world is blocks of dilapidated buildings, closed storefronts, and empty lots strewn with piles of illegally dumped trash.

On Ridge, Qu-ran and his friends dodge traffic — and an aggressive drunk who thinks they’re trying to videotape him.

Eventually, the group reaches the Cecil B. Moore Library, a single-story building near one of the many busy intersections that dot the avenue.

Qu-ran walks through the turnstile and greets a man at the circulation desk.

“What’s up, little buddy,” the man asks.

Of all the spots Qu-ran and his friends frequent, the library feels the brightest and best kept. It has a newly redesigned play space in one wing and a bay of computers in another. Keeping one’s voice down may seem suffocating, but it’s well worth 30 minutes of air-conditioned calm.

Qu-ran decides to reserve a computer and watch a few YouTube videos. He likes a genre of videos he calls “hacks,” which often involve people using DIY methods to enhance some sort of household product.

“Oh snap…that’s tough,” he says as he watches a guy use colored markers to decorate tennis shoes with eye-popping patterns.

“I mess up my sneakers, my mom would smack me for that,” he says.

Qu-ran mentions, without prompt, that his dad is from West Africa and got deported after catching a drug charge. Then, it’s back to more videos, and eventually the street.

Mid-afternoon is a slideshow of corner stores and junk food. Qu-ran grabs gum and something he calls “Philly punch” at one store before meeting some friends at a nearby bike rack.

With that drink downed, it’s back to the corner store — or the “Papi” store as Qu-ran calls it, a reference, he says, to the hispanic families who run many of the shops in the neighborhood. He haggles with a man behind the counter over a popsicle.

— How much is this?

— 75 cents

— Lemme get it for a quarter.

— No.

— I come here all the time!

— No, you don’t.

Eventually, Qu-ran ambles back to Hank Gathers where Jimmy Richardson greets him.

There’s some half-formed, half-court games on the outdoor blacktop. Qu-ran pulls up the music video for a song called “Handgun” on someone else’s phone. He raps along. A couple of older kids stroll up and start busting on the way he looks. Qu-ran laughs it off.

Qu-ran’s world is like one of those video games where you walk around without a real objective. No one seems to pay you much mind. You ping pong from place to place — from the public rec center to public housing to the public library and back again.

There was something quaint about it. It felt like the summer days of yore: aimless, unstructured, unbounded. Qu-ran was the star of his own slice of life, coming-of-age movie.

— Hey, Big Booty Judy! I’m in love with her.

After another trip to the corner store and the housing projects, Qu-ran again returns to Hank Gathers. Seated on aluminum bleachers next to the outdoor basketball courts, he grabs the same phone he borrowed before. He doesn’t have his own yet, but swears he will soon.

He pulls up another YouTube video — this one of a doctor performing brain surgery. The topic fascinates him. He hopes someday to earn a basketball scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania so he can become a surgeon.

It’s clear he has seen this video before.

“See, to tender it up they put water on it,” he says without lifting his eyes. “You see?”

Qu-ran’s restless, wandering energy ebbs for a moment. He’s totally absorbed in the video.

Motorbikes roar by, the sound of sunset in North Philly.

Some other aspiring surgeon probably spent the day at science camp. Qu-ran doesn’t have that. He has an eight-minute YouTube video and a pending offer to play three-on-three.

He leaves Hank Gathers as evening descends. It’s back to the corner store one more time, and then into the night.

***

It’s still August. Another Friday night at Hank Gathers, and the kids out on the playground are in high spirits.

Players run a full court game, many of them shirtless in the sweet summer night air, driving the lane for layups. When the ball falls through the white net, the guys crow only briefly as they hustle back on defense.

Over on the bleachers, a group of kids watch the game with one eye, sharing their own laughter.

Girls, some with polished Friday-night looks, linger by a chain-link fence.

At a break in the game, Shawn and one of his friends grab our microphone and mock as if they’re television news reporters.

— Yo, we live from the trenches.

— We live from where?

— 25th and Diamond.

The co-ed mix on the playground creates waves of flirtatious energy.

Jaheed, 14, gives a rundown of who he believes to be “the thrillest.”

Greg wanders over and starts rapping. He loves an artist from Savannah, Georgia named Quando Rondo.

Only reason why I went on that lick ’cause I got tired of hustlin’

Mama couldn’t pay the bills and I know she tired of strugglin’

Ever since I was a lil’ one, I ain’t had nothin’

Walk a mile in my shoes, you’ll see that I ain’t frontin’

I know one day I’m gon’ make it, ’cause I grind for it

Distance myself from that fake shit, I ain’t got time for it

Greg says he was kicked out of Edison High School. He pulled on a teacher’s scarf. He says he thought he was being playful. The staff didn’t see it that way. He now goes to the same school as Qu-ran, Camelot, the one for kids with disciplinary problems.

As Greg talks, Shawn joins in.

— I actually like Camelot, though.

— Yeah, he actually likes Camelot because he can do anything in there. That’s why.

— No, no. I like Camelot because…

— That’s not a good school for you. You can’t go nowhere, bro. Where you going from that school, bro?

Greg shakes his head and laughs. Shawn looks beyond his friends to the passing traffic.

— My mindset is higher than theirs. I got more knowledge than them, and all that.

— No it’s not. No you don’t.

Shawn puts his arm around Greg’s neck, smiling. We’d been asking him questions all summer. Now, he levels with us, as if this is the only answer that matters.

— Listen man, we just some young bouls trying to get out the ‘hood.

We ask Shawn about Greg.

— You believe in him?

— Yeah, I believe in him.

— What’s his gift? What’s he going to do?

— Rap. He’s a rapper. He can play ball a little bit, but he’s not me.

Basketball player. Rapper.

Hank Gathers is full of kids with dreams of making it big — as Jaheed and Greg explain, a hope that talent will lead to a pay day that will whisk them to another life.

— When we make that money, Philly ain’t going to be thought of. We trying to go to like California, Florida. We’re going where the money at. That’s what we’re chasing.

— We’re chasing a bag.

— We’re chasing a bag. You hear me?

— Chasing that money.

Maybe, for some kids, that will happen. If it happened for Kyle Lowry, Dawn Staley, and the Morris twins, why not?

But the story at Hank Gathers is as much about the kids who stay.

***

The first time we met Rahdeem Abdullah he was in the middle of managing a meltdown.

He’s a behavioral support specialist in public schools near the rec center. The kids he works with have issues that call for year-round attention. So, during the school year, he’s in the classrooms. In the summer, he’s often at Gathers, working with students in the day camp.

We were talking inside the Gathers gym when one of his students stormed out upset. He quickly followed, calmed her with a hug, and guided her away from the crowd into Jimmy and George’s room.

When they came back out, she was ready to play again.

“See, I work with her,” Abdullah said. “I know she’s very explosive.”

Abdullah, 33, who grew up poor in a neighborhood not far from Gathers, is a unique bridge between the world of school and the world of summer. He sees it all.

“You see it all the time, you know, you have kids watching themselves,” he said. “They go through a lot. They go through a whole lot.”

To him, working with kids comes naturally. He has an easy rapport — he knows how to connect, how to disarm, when to be patient.

“Behaviors is easy,” he said. “If I just had to deal with behaviors — that’s just the easy part.”

He knows, though, the job can be much more difficult for teachers, especially those who aren’t as familiar with the neighborhood. We spoke outside of Frederick Douglass Elementary — a school a few blocks from Gathers where he often works.

The school has changed hands a few times in the past decade. The district turned it over to charter operator Scholar Academies, who then turned it over to Mastery Charter. It’s long been considered one of the city’s toughest assignments.

“If you don’t understand the kids you’re teaching sometimes, you’ll definitely get frustrated. And it’s all a misunderstanding sometimes. And I think that’s what’s happened with a lot of our kids,” said Abdullah. “You have many teachers that’s not from the culture, trying to understand the culture. But they don’t quite get the culture. They only learn by textbook way, and sometimes they get so frustrated because they don’t teach you that. There’s no manual for that.”

Abdullah is lucky to have made it past 18. After graduating from Simon Gratz High School, he worked full time at a downtown hotel while taking community college classes on the side. At first, he did it to please his mom, but he met new people, made connections with professors, and really started to like it.

Then, suddenly, he was struck in a drive-by shooting as he and a friend were on his porch.

“[The bullet] went through my shoulder and hit my spinal cord,” he said.

To this day, he says he doesn’t understand why it happened. The shooter was never apprehended.

Abdullah was paralyzed from the waist down. At first he was despondent. But, day after day, week after week, as family and friends came to support him, it changed something in him.

“You see them crying and you see them willing to change their life for you — and you don’t want that for them,” he said. “So you start working out for them. You want to be better for them. That’s where I started. The support.”

It was four months before he could wiggle his toes. Two years of rehab before he could walk on his own.

After his recovery, he pushed himself to find a more meaningful career. He went back to college and wound up in a course on forgiveness that helped him process what he’d been through.

“We always say, ‘Who would do this to me? I don’t bother nobody. I don’t do anything to nobody. Who would even want to disrespect me?’ Like, I would put it in the category of ‘disrespect.’ Like, this is a disrespectful moment that could have cost my life,” he said.

But as he thought about it more, he decided he couldn’t allow his anger to control him. He didn’t want to give the shooter that power.

“There are things in life you just can’t account for — you can’t explain. We don’t got the answers. People spend a whole lifetime trying to figure out answers. Sometimes things happen just because they happen,” he said. “Whether things are fair or unfair — we gotta get through, gotta push through.”

Abdullah finished his bachelor’s degree in criminal justice from Chestnut Hill College, but then, as he thought back to his rehab, he decided education was the best way to make a positive impact.

“I understand why support really matters,” he said. “If a kid don’t got support, who’s he going to do it for? What is his motivation? Who is his inspiration? That’s what helped me — my support system. And I’m, like, ‘Yo, I got to do it for them.’”

Now, he’s a Zen figure in the classrooms and the rec centers of North Philly, preaching a message of forgiveness, of rising above — helping kids who might otherwise act out and get suspended, stay on track.

“I might save a kid from three to four suspensions that might get him kicked out of school. That right there is an opportunity that you might save a kid long enough where he can make a positive adjustment in life,” he said. “To me, that’s validation — that just makes you feel so happy.”

When you see Rahdeem Abdullah with the day camp kids over the summer, the comfort and connection students feel with him is crystal clear.

For many kids, he was a pillar of the summer.

Same goes for Aunt Cheryl Hardy, George Major, Jimmy Richardson, Howard Bolden and other rec center staffers. They may not be the wildly rich stars the kids aspire to be, but their power and influence may prove even greater.

They are people who have seen the highs and lows of life in North Philadelphia — people who could choose, if they wanted, to turn their backs on it.

But people who, for the sake of the kids — the community — stay and work to keep this little patch of the city holy.

And there’s an architecture to it: The little camp kids of yesterday become the teen counselors of tomorrow. The counselors keep coming back, even after going to work or going to college.

One day, decades from now, it’s not hard to imagine that those armchairs of Jimmy and George will be occupied by some of the kids we met this summer.

A handshake passed down through generations.

***

Summer ended early in Philadelphia in 2018. Classes started in late August.

The rec center got back to its school-time routines.

A few weeks into September, we were still thinking about the kids we met over the summer, wondering how they were doing. We swung by Gathers on the way home from work on a Friday.

Like clockwork, Shawn and his friends are on the playground.

“Summer? It was alright man. It was a fun summer at Hank,” said Shawn. “All I did at Hank was play ball, went swimming, go on trips with Aunt Cheryl, work at the camp.”

Shawn actually did something else pretty big over the summer. He and Greg converted to Islam on the same day.

“What I study is something that changed my life — I pray at least four times a day,” said Shawn. “It helps me get focused. Ramadan — it helps me clean my system out. It makes me positive, more positive.”

For Shawn, it’s a spiritual journey to complement his physical journey.

Both, though, are rooted in the same thing: a 15-year-old from the projects figuring out who he is, very consciously pushing to make himself better, trying to mold something stronger than what came before.

The gravity of our conversation passes and soon the kids are laughing and singing into the mic again.

After a little while, we, the reporters, head out. The kids stay.

It’s Friday night. Monday morning’s classes are a far-off thought — and there’s still plenty of time before the court lights go dark.

—

This season of Schooled included two other stories, “Last Chance High” and “Don’t Eat the Marshmallow.”

Many people contributed to the production and promotion of the season, including Naomi Starobin, Charlie Kaier, Naomi Brauner, Evan Croen, Erin Reynolds, Zoe Grossinger, John Sheehan, Emily Gann, Joy Soto, Elyse Poinsett, Eugenia Krug, Stephanie Walker, Tory Harris, Sakeenah Benjamin and Robert Deiters.

Schooled is made possible with support from the William Penn Foundation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.