Wonks weigh in on how Wolf should help cities

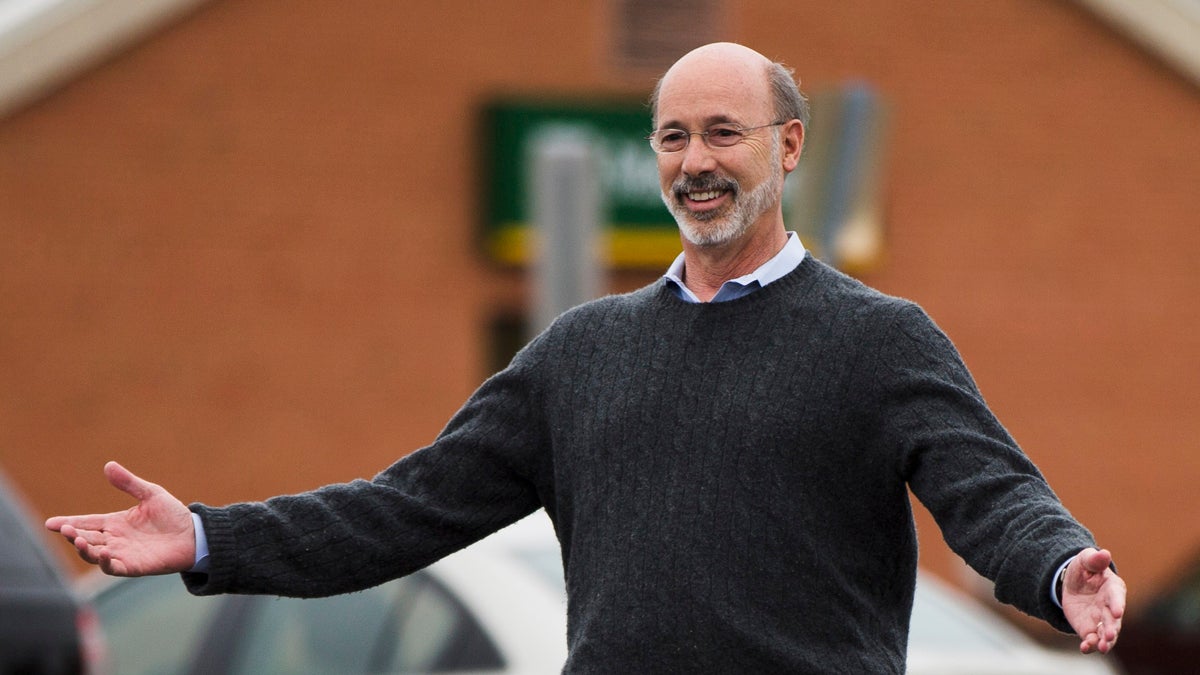

Keystone Crossroads asked a cross-section of mayors, consultants and other experts: how should Gov. Tom Wolf prioritize plans for fixing Pennsylvania's cities? (AP File Photo/Matt Rourke)

Keystone Crossroads asked a cross section of mayors, consultants and other experts: how should Wolf prioritize?

Gov. Tom Wolf hasn’t really talked during his first week in office about his plans for fixing Pennsylvania’s cities. Wolf spoke about it during his campaign, but not since his term started last week – aside from glancing references during his inauguration ceremony about efficiency and stripping away “silly,” antiquated laws.

So Keystone Crossroads asked a cross section of mayors, consultants and other experts: how should Wolf prioritize?

Everyone was hard-pressed to pick just one in the “ox cart of government laws that should be changed,” as the Pennsylvania Economy League’s Brian Jensen put it.

This is what they said:

Change the rules for binding arbitration, which would help fix costs associated with pensions and other compensation.

Public safety unions are barred from striking by Pennsylvania’s Public Employee Relations Act.

So if contract negotiations with local governments reach an impasse and go to a mediator, the decision is binding – meaning municipalities generally can’t appeal it. Or, they can, but aren’t likely to succeed.

The problem is, those decisions often yield contract terms that municipalities cannot afford to honor without raising taxes excessively or drastically cutting other services, according to Pennsylvania Municipal League Executive Director Rick Schuettler.

Health care, minimum staffing complements, work rules – all are subject to arbitration board rulings, says Jensen, who runs the League’s Pittsburgh-area office.

And so are pension benefits – and that’s what nearly everyone mentioned, including Jensen, Schuettler, the Lancaster task force, the city of Reading’s Act 47 coordinator Gordon Mann and Teri Ooms, who heads The Institute for Public Policy & Economic Development at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre.

Underfunded pensions are a national problem.

In Pennsylvania, experts say, it is largely pension obligations that have lead to near bankruptcies and resulted in state interventions in Reading, Scranton and Pittsburgh.

Some believe changing the rules of collective bargaining would help.

This is why:

Often, local elected officials agree to adjust other compensation in lieu of – or in combination with — wage increases sought by unions. That might include decreasing the amount employees have to contribute toward their pensions, increasing their retirement payments, or both.

State and local taxpayers pay more if government officials decide to make up the difference for decreased employee contributions. If not, taxpayers likely would have to make up for it in the future when current those employees retire.

“Leveling the playing field on binding arbitration would make a tremendous difference in the financial health of Pennsylvania municipalities,” Jensen says.Schuettler, Jensen and others – including members of the city of Lancaster’s municipal task force – say state law should require:

The Commonwealth to randomly assign arbitrators to negotiations. They say unions and municipalities now choose their own arbitrators, which compromises neutrality.

An even split of arbitration costs, now borne primarily by municipalities.

Arbitrators to document they’ve considered the municipality’s ability to cover contract costs, and found them affordable.

Changes have been proposed, but didn’t make it past a state Senate Local Government Committee hearing last spring in Lancaster.

Allow cities to levy more types of taxes

Sales, retail alcoholic drinks, business gross receipts, and nonresident worker wages all have been broached as potential revenue sources. But it can’t happen without state lawmakers amending the Local Tax Enabling Act (Act 511), as recommended by Lancaster’s Municipal Task Force.

Regionalize tax revenues

Eric Menzer, who owns professional minor league baseball team the York Revolution, says countywide taxes should help pay for services in government centers. County seats, like York, have a lot of property owned by the government, hospitals, educational institutions and charitable organizations – none of which have to pay property taxes. That severely restricts tax revenue, leaving “a city like York trying to run a government for 40,000 (residents) and 40,000 (nonresident) workers on the backs of a tax base that’s …. 40 percent exempt,” says Menzer.

Menzer – who doesn’t pay real estate taxes on Santander Stadium, but gives the city money through a PILOT agreement – says the answer is not changing how “purely public charity” is defined. He says exempt organizations locate to York and similar cities – including Lancaster, Harrisburg and Johnstown – because they’re centrally located for the many nonresidents served and employed.

“The higher proportion of tax-exempt properties makes the point that these communities are the center of a metropolitan region, … and we ought to pay for that at a metropolitan level,” Menzer says.

Ultimately, that would also decrease some of the taxes and fees Menzer says discourage people from living in cities that otherwise would be economic assets.

Raise the bar for companies to qualify as exempt from property taxes

York Mayor Kim Bracey agrees with Menzer about York’s regional importance, and the imbalance in service provision and funding created by tax exemption there and in other government centers.

But she does think rules need to be stricter for earning tax-exempt status.

“Something as basic as requiring a regular reassessment should be in place,” Bracey says.

Mandate, or increase incentives for, service-sharing or complete consolidation at the local level

Restore funding for the state Department of Community & Economic Development, says Michael McKenna, Economic Development Coordinator and Elm Street Manager for the City of Lebanon.

The current $204 million budget is down from $327 million four years ago – and the $631 million allocation four years before that – for DCED, the main source of revitalization money for Pennsylvania’s communities.

Increase the threshold for government contracts that require public bidding

The current $10,000 figure was established “decades ago,”and many more contracts now trigger the expensive, “cumbersome” process, according to Lancaster’s municipal task force report.

The report advised increasing it to $100,000, adjusted annually according to the consumer price index.

Allow paid fire departments to compete for state grants and low-interest (2 percent) equipment loans.

Currently, the Commonwealth only considers volunteer fire companies, according to the Task Force.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.