Why the pope’s upcoming summit needs to do a full accounting of the cover-up of sexual abuse

Recent statements by leading bishops and the pope suggest that church officials are not ready to take what I believe is an essential step in ending the scandal.

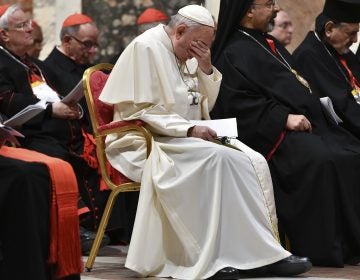

Pope Francis sits during the traditional greetings to the Roman Curia at the Vatican in December 2018. (Filippo Monteforte/Pool Photo via AP)

Pope Francis is gathering 200 bishops and heads of religious orders from around the world for a global summit in Rome to discuss the crisis facing the Catholic Church over sexual abuse scandals.

The meeting begins on Feb. 21 and will last four days. It is likely to produce a new round of public apologies, expressions of concern for victims and pledges of reform.

But recent statements by leading bishops and the pope suggest that church officials are not ready to take what I believe is an essential step in ending the scandal: providing a full and detailed accounting of their own role in concealing credible allegations of sexual abuse.

I’m a legal scholar who has written a book on clergy sexual abuse in the Catholic Church, and it appears to me that the church’s latest response, so far, is part of a familiar pattern that has persisted for nearly three decades.

Recent revelations

In 2018, the scandal of clergy sexual abuse in the Catholic Church once again made headlines around the world.

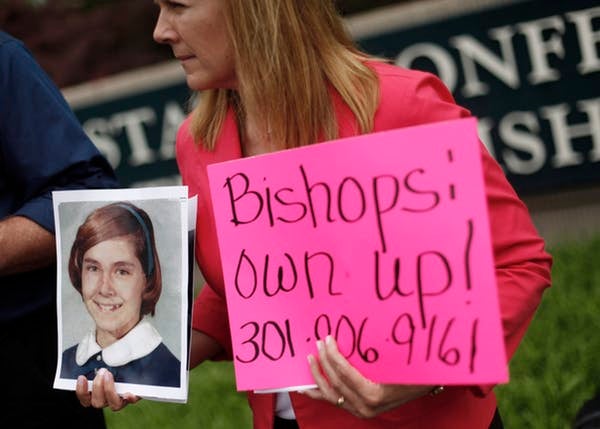

In August, a Pennsylvania grand jury that investigated abuse in six dioceses over a period of 70 years found that bishops in the state failed to report credible sexual abuse allegations against 300 priests involving 1,000 children.

No indictments have been issued by that grand jury. Most of the abuse occurred decades ago, and the statute of limitations has expired on almost all of these allegations.

Later that month, Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano, a former top Vatican official and a long-time critic of Pope Francis, issued a press release alleging that senior Vatican officials and Pope Francis had covered up abuse allegations against Cardinal Theodore McCarrick of Washington, D.C.

Vigano claimed that he personally told Pope Francis in 2013 of sanctions imposed on McCarrick by Pope Benedict XVI in the late 2000s – but that Pope Francis repealed them and made McCarrick a trusted counselor.

The Vatican finally removed McCarrick from ministry in June 2018.

Although Pope Francis vigorously denies Vigano’s allegations, which remain unsubstantiated, bishops and Vatican officials had received reports for decades of Cardinal McCarrick’s transgressions. The New Jersey dioceses where he served as bishop paid legal settlements, the details of which remain sealed, to two of his alleged victims in 2005 and 2007.

In December of 2018, another investigation by the Illinois attorney general concluded that bishops in that state withheld the names of more than 500 priests accused of molesting minors. More than a dozen similar probes are currently underway by attorneys general in other states.

Revelations like these have not been limited to the U.S. Similar investigations, spanning the globe from Chile to Germany to Australia, have exposed sustained efforts by church officials to conceal sex crimes.

A familiar pattern

Although the scandal of sex abuse by clergy did not come to light in media reports until the 1980s, personnel files in dioceses around the U.S. contain allegations of sexual misconduct against priests dating back to the 1930s.

The issue was openly discussed in biannual meetings of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops in the 1970s. During this time, the organization funded a treatment program specifically for Catholic priests who sexually abused minors, and issued directives regarding the retention and destruction of treatment reports provided to bishops.

Every U.S. bishop involved in these meetings and who referred priests for treatment during this time knew of the problem.

However, public acknowledgment by church officials of clergy sexual abuse did not begin until 1984, when the case of Father Gilbert Gauthemade national headlines.

Gauthe, a popular parish priest in rural Louisiana, sexually abused dozens of prepubescent boys. His crimes were finally exposed when victims and their families sued the diocesan officials who knew of the abuse but had failed to remove Gauthe from ministry.

The local bishop issued a public apology and expressed sympathy for the victims. The National Conference of Catholic Bishops issued recommendations to dioceses in 1987 for preventing and reporting abuse.

Eight years later, in 1992, sexual abuse victims publicly exposed Father James Porter, who molested more than 100 known victims between the ages of 6 and 14 while serving as a priest in parishes in Massachusetts, Minnesota and New Mexico. His predatory behavior was well-known among his colleagues and superiors within the church.

Local bishops once again apologized and held “healing” masses for victims, and the National Conference of Catholic Bishops endorsed a set of five principles to guide dioceses in responding to allegations.

These included conducting prompt investigations, removing accused priests in face of credible evidence, reporting allegations to civil authorities where required by law, extending pastoral care to victims and their families, and seeking treatment for offenders.

Nonetheless, the scandal resurfaced in 2002. The most egregious offender in this round of revelations was Father John Geoghan, who reportedly abused more than 800 victims over a 33-year period in Boston parishes.

Geoghan’s crimes were concealed by no fewer than six bishops, including Cardinal Bernard Law, the archbishop of Boston and arguably the most powerful figure in the U.S. Catholic Church.

For a third time, in 2002, the bishops issued apologies, acknowledged the suffering of victims and published new reforms in the Charter for the Protection of Children & Young People, including “zero tolerance” for clergy sexual abuse within the church.

Lack of accountability

For more than three decades, in the face of intense media coverage and public outrage, the bishops have attempted to deflect blame for the crisis.

One strategy has been to blame the crisis on contemporary attitudes toward sexuality.

Take the example of Bishop Edward Scharfenberger of Albany, New York. He issued a recent statement in response to the Pennsylvania grand jury investigation explaining that,

“I do not see how we can avoid what is really at the root of this crisis: sin and a retreat from holiness, specifically the holiness of an integral, truly human sexuality. In negative terms, and as clearly and directly as I can repeat our Church teaching, it is a grave sin to be sexually active outside of a real marriage covenant.”

He went on to lament that “contemporary culture in our part of the world now holds it normative that sex and sexual gratification between any consenting persons for any reason that their free wills allow is perfectly acceptable,” and he called for “a culture of chastity” to “drive the evil behaviors among us from the womb of the church.”

Pope Francis echoed this sentiment when he told reporters recently that “we have to deflate expectations” about just how much the church can do “because the problem of abuse will continue, it is a human problem.”

A focus on prevention

It is true that church officials have made efforts to reduce the incidence of clergy sexual abuse.

For example, bishops have implemented training programs within most dioceses throughout the U.S. for those who work with children. Initial efforts began in the mid-1980s and expanded rapidly after 2002.

A comprehensive study by researchers at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice suggests that the incidence of clergy abuse has been steadily declining since the 1980s. These researchers speculated that the bishops’ efforts may have contributed to this decline.

Yet, despite diocesan reforms and the declining rate of abuse, the scandal persists.

The missing ingredient

Pope Francis recently told reporters that the upcoming Vatican summit will include a “penitential liturgy to ask forgiveness for the whole Church,” testimony from victims to make bishops “become aware” and the establishment of new “protocols” for handling abuse cases.

This agenda for the upcoming summit fits the now-familiar pattern of apologizing, expressing concern for victims and pledging reform.

The pope also indicated in his remarks that the summit would focus on the need for sex education that adheres to church doctrine. In other recent remarks to the media, the pope demanded that priests who have raped and molested children turn themselves in, and he vowed that the Catholic Church will “never again” hide their crimes. He pledged that “the church will spare no effort to do all that is necessary to bring to justice whosoever has committed such crimes.”

This plan for reform – promoting church doctrine on sexuality, calling out priests who have perpetrated abuse and pledging to clean house in the future – is missing a key ingredient necessary to quell the crisis: Until church officials provide a full accounting of their concerted efforts over decades to hide crimes from civil authorities, parishioners and the public, the clergy sexual abuse scandal, I believe, will not go away.

![]()

Timothy D. Lytton, Distinguished University Professor & Professor of Law, Georgia State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.