Why is SEPTA Key arriving two years late?

SEPTA Key is the Philadelphia straphanger’s Godot: a tale of absurd waiting, punctuated by the occasional news that the long anticipated “won’t come this evening, but surely tomorrow.”

If SEPTA does launch the new payment technology (NPT) fare system sometime this spring, as the authority now says it hopes to, it will arrive more than two years late.

SEPTA’s contract with ACS Transport Solutions Group originally scheduled NPT implementation for December 2013. But the issues disrupting service on-time delivery of SEPTA Key began well before that contract was signed.

SEPTA released its Request for Proposals (RFP) – the formalized, public way of asking for interested contractors to submit bids on a project – back in November 2008. The authority originally hoped to start accepting bids the following March. But that was delayed, and then delayed again, and then delayed some more.

Meanwhile, SEPTA continued to change the project’s parameters. As the would-be contractors raised unanticipated questions, SEPTA modified their bid documents in response, said SEPTA Key Project Manager Kevin O’Brien: “It was actually sort of the design process part of it because we didn’t know what kind of technology [the bidders] were going to propose. So they proposed technology and we had to make sure that our specs and all incorporated, and accept all those technologies.”

SEPTA officials prefer to blame the delays during the RFP process on funding constraints. Before Act 89’s passage in 2013, the SEPTA capital budget was barely enough to keep the trains running, literally. A doomsday scenario predicted nine regional rail lines shuttered. But SEPTA received a $175 million loan for SEPTA Key in January 2011 from PIDC’s EB-5 investor visa program, which effectively sells visas to wealthy foreigners in exchange for job-producing investments. Even at a low rate of 1.75 percent interest, the debt offering still managed to attract hundreds of foreign investors over other large projects seeking EB-5 investment, including private sector opportunities. Investors considered SEPTA a safe investment.

While SEPTA secured funding, it continued to tweak the RFP. By the time ACS executed its contract with the transit authority, SEPTA had released 26 addenda to the original bid documents, each modifying the scope and specifications for the NPT system.

Simply put, SEPTA did not know what it was asking for when it requested proposals back in 2008. The authority knew it wanted a comprehensive fare system for all its modes, something no other large U.S. transit system had, and a solution with the flexibility to adapt to new technologies. But as of 2011, SEPTA was still debating how it would collect fares with the new system on regional rail, considering for a while a one-way collection fare with free inbound trips and double-priced outbound trips.

During the bidding process, project managers said it might take just two short years to get NPT up and running. By the time an actual contract was signed, it still predicted SEPTA Key’s deployment on buses, trolleys and subways in two years, but bumped out regional rail to just under three.

The enormity of the project was slowly beginning to dawn on SEPTA’s management.

EASIER SAID THAN DONE

“People never have a sense of how complex something is until they get into it,” said David Schuff, a Professor of Management Information Systems at Temple, speaking generally about large-scale information system projects like SEPTA Key.

“It’s almost a form of willful optimism that everything will work out and unfold as you’d expect,” Schuff explained. “And then as you get into it, there are layers of complexity you didn’t know were there before.”

You could argue that SEPTA Key isn’t arriving late so much as its ETA was way too early. Bidders competing for public contracts have plenty of incentive to over-promise on delivery dates. SEPTA repeated ACS’s proposed completion dates to the public, raising expectations for a relatively swift end to tokens.

O’Brien can rattle off the names of cities that sat impatiently through belated fare card overhauls. “Cleveland, five years late; Pittsburgh, three years late; Boston, two years late; [Chicago Transportation Authority], who was super fast, was one year late.” He says. “NYC MTA—the RFP, just the RFP alone, is 2 years late. And they’re projecting to 2023 [to upgrade their fare system].”

SEPTA Key’s software has “millions and millions of lines of code” says SEPTA General Manager Jeff Knueppel. SEPTA Key requires the authority to completely change how they handle Regional Rail fares. On top of the software and process changes, SEPTA Key calls for 1,850 onboard fare processors, 350 vending machines, 650 turnstiles, 550 platform validators, 300 parking payment stations, 480 handheld sales devices, 1,200 offsite card purchase locations and 2,000 card reload locations. The original specifications for the new NPT system ran 888 pages long.

SEPTA Key is a big project. Big projects take time. Transportation agencies in other cities spent three-to-five years upgrading their fare systems. And SEPTA Key is more ambitious than any of those projects were.

In other cities, the transportation network consists of just two or three modes – buses, subways, and maybe a paratransit system. SEPTA has six: those three, plus trolleys, regional rail, and the Norristown High Speedline (trackless trolleys are basically buses as far as the fare system is concerned).

“We’re one of the largest most complicated transportation systems in the country,” says Schuff. To him, the belief that SEPTA Key would happen faster than simpler systems just because it’s coming later was a serious mistake.

It’s a criticism that SEPTA accepts, to a point. “We were maybe off in underestimating the time it takes to do this,” said O’Brien.

In terms of system complexity, adding another mode isn’t a matter of basic addition and modification. The intricacies involved in developing software and hardware solutions increases exponentially with each layer, said Schuff. “You’re taking [six] different processes and making them into the same one.”

SEPTA Key is designed to be an open system, meaning any contactless card or smartphone equipped with Near Field Communication (NFC) technology could use it. SEPTA Key will be one of the first in the world with that capability. And developing a system that can interact with different types of hardware and communicate across different operating systems is no small task.

“This is a single, multiphase project that will contain everything,” says Schuff. “They’re trying to create a system now that they don’t have to redesign for the next phase. So, they need to take into consideration everything they want to do in the future, [right] now.”

SEPTA Key’s development has been arrested since May, when it entered pilot testing. So far, over 400 bugs have been found and corrected, says O’Brien. Just a few remain, mostly affecting accounting on the backend.

CH-CH-CH-CH-CHANGES… TIME MAY CHANGE ME, BUT I CAN’T TRACE TIME

Even after the 26 addenda, the final contact for SEPTA Key wasn’t set. Since it was signed in December 2011, the contract has been amended 10 times by formal change orders. Each change order modifies the scope of the underlying project by amending or adding to the technical specifications. The specifications, already a massive 888 pages long, grew to 922 pages following the second change order.

Even for a project of this magnitude, the 10 change orders indicate that SEPTA and the consultants hired to help draft the specifications and other RFP documents, LTK Engineering Services, did not really understand just what they were trying to accomplish, says Nasser Tehrani, a senior project manager at Technology Evaluation Centers who specializes in managing business process overhauls like fare payment system upgrades.

“One of the huge risk factors [in these projects] is really from the beginning, which is to come up with a very clear and solid scope [of work],” says Tehrani. “If this type of initiative [SEPTA Key] is lacking a clear and solid scope, it will definitely go wrong.”

Numerous changes to the project’s specifications before and during the design and implementation suggest that SEPTA was in way over their heads, even with LTK’s support. LTK advises clients on a wide range of rail related projects, focusing primarily on vehicles, signaling and control systems.

LTK did not respond to PlanPhilly’s request for comment.

Some of the change orders were small, like increasing the number of customer kiosks or adding more turnstiles to the final set of deliverables. Others were initiated by ACS in response to issues they did not foresee. But some change orders fundamentally affect the scope of the project, and the largest changes came at SEPTA’s behest.

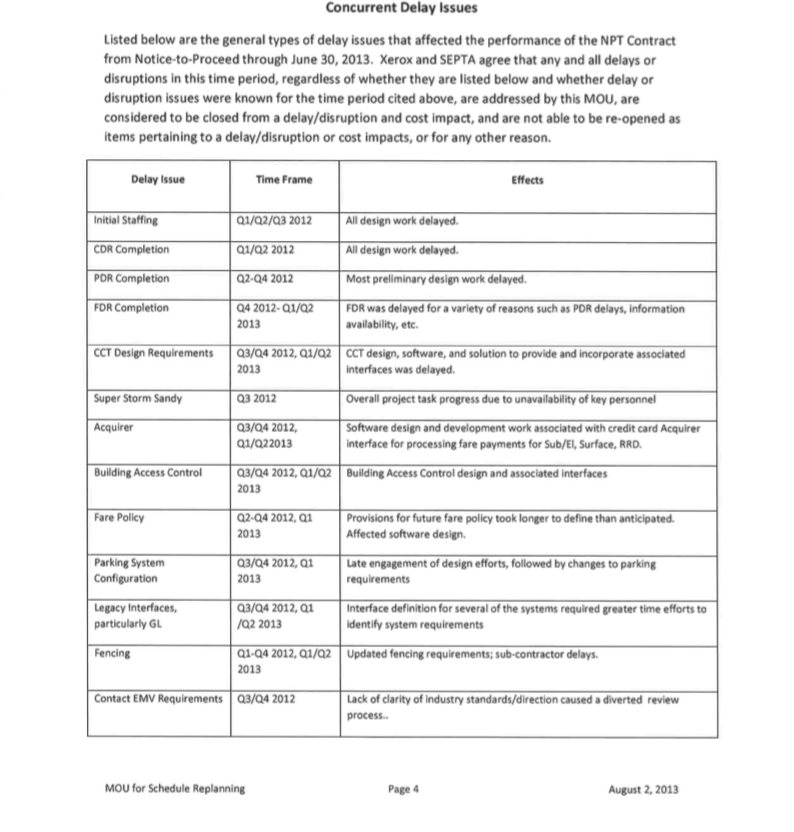

A litany of issues plagued the project early on, causing delays and requiring a change order, which—including attachments—runs 134 pages long.

With nearly every change, the project’s price tag increased. The latest change order raised costs to $140.6 million; it started at $122.2 million.

The change orders have also pushed back ACS’s deadlines for delivering a functioning system, but not by much. The deadline for finishing Phase 2, which includes launching SEPTA Key on subways, buses and trolleys, was extended to June 30, 2014 from an original date in February 2014. As of today, it is now 540 days late.

The deadline for Phase 3—implementation on regional rail and in SEPTA’s parking lots—was pushed back to Dec. 31, 2014. SEPTA officials say that might not be complete before 2017.

Missing the deadlines could cost ACS, but just how much is hard to say. The contract requires ACS to pay “liquidated damages” for every day past deadline until it completes a phase: $3,700 per day for Phase 1, $10,850 per day for Phase 2, and $18,150 per day for Phase 3.

SEPTA accepted Phase 1 deliverables Oct. 31, 2014, 304 days after deadline. If SEPTA meets its new estimate for preliminary launch starting by April 2016 and a finished system by the end of the year, Phase 2 would be 640 days late, and the final phase 732. Add it all up, and you get $21,354,600.

But even if the deadlines don’t change and those targets are made, SEPTA won’t get $21.4 million. The contract limits liquidated damages to 10 percent of the final contract cost. The most SEPTA could legally claim would be $14.6 million.

And even that $14.6 million figure is suspect because the NPT contract doesn’t explicitly say whether these damages are meant to be cumulative.

Lawyers use liquidated damages to avoid costly lawsuits over relatively minor contract breaches, like performance delays, by stipulating payments for those breaches. When SEPTA’s lawyers drafted this liquidated damages provision, they unilaterally decided to cap liability at 10 percent—no one forced them to or negotiated that specific percentage.

Liability caps can help attract more bids, as do any other favorable contractual terms. But by setting a ten percent cap on delay damages, SEPTA all but ensured it would receive unrealistic timelines from the bidders.

In order for stipulated fees for tardy deliverables to actually motivate a contractor to perform quickly, they need to really hurt profitability. Liability caps are like morphine: they make the pain go away. Once the limit is reached, additional delays stop stinging, allowing a contractor to take as long as they want without forfeiting more money.

That problem is exacerbated when limited competition all but ensures inflated bids, as was the case here. Only three companies bid for the NPT project.

“The industry just isn’t very strong,” said Knueppel. With just a few companies competing for these large bids, transit agencies like SEPTA lose bargaining power.

Incentivizing speedy delivery through stiff penalties comes with its own problems. Chicago’s contracts for a new fare system did just that, causing their contractor to rush implementation. That system’s debut was a complete debacle that SEPTA desperately wants to avoid.

And delivery deadlines are liable to change again. “There are outstanding PCOs [potential change orders],” confirmed Andrew Busch, a spokesman for SEPTA. Another change order could push the deadlines back again to compensate ACS for the delays caused by SEPTA.

SEPTA: A+ IN CIVIL ENGINEERING, C- IN C++

SEPTA Key’s first project manager was John McGee. McGee earned an MBA from Widener but lacked experience with big technology projects. McGee retired from SEPTA in 2014, and immediately joined LTK as a senior consultant. The SEPTA employees overseeing ACS’s design and implementation work are well versed in the intricacies of SEPTA’s fare policies and accounting systems, but lack software savvy.

Technology hasn’t been SEPTA’s strongest suit. A week ago, its mobile app posted inaccurate information following a scheduling change. Back in July, the authority’s website for mass transit tickets during the Papal visit crashed within seconds of going live. That inspired more than one hyperbolic wag to draw analogies to Healthcare.gov’s disastrous launch.

But there’s more to the comparison between SEPTA Key and Obamacare than snark. While the website’s terrible initial launch is infamous, lesser known is the administration’s response. Following the costly launch failure, Healthcare.gov was saved by small team of designers and developers. The original website system cost $250 million to build and $70 million a year to maintain. The new, working system cost just $4 million to build and $1 million per year in upkeep.

Hiring a team of computer programmers to work in house didn’t just save the Affordable Care Act, it saved millions of dollars, too. And in the process, it highlighted how government entities need to rethink their approach to technology projects.

“If the successes of the MPL team confirm any guiding principle for the future, it is this,” writes Robinson Meyer for The Atlantic. “Technical workers—not only engineers but designers—have to be involved with a process from the beginning. They will know that features must be described separately from needs, and that, when building software, smaller teams often perform better than larger teams.”

It’s a point James Somers drew on for another article in The Atlantic, which explains why New York’s subways, like Philadelphia’s, lack countdown clocks. Attempts in the 90s and early 2000s to provide bus arrival information failed, ending in canceled projects and fired contractors. In 2010, the MTA hired a “small team of software-savvy MIT grads to come in-house and manage the bus project.”

The team designed their specifications in house, and brought in smaller contractors to build each element. It worked. Less than a year later, BusTime debuted on a bus route in Brooklyn.

“Having full-time software experts running the show turned out to be crucial. Previous incarnations of the project didn’t have a technical leader at the MTA—just old-school senior managers who would try to wrangle the contractors by force of will,” writes Somers. “The new in-house team, by contrast, was qualified to define exactly what they wanted from software providers in terms those providers could understand. They were qualified to evaluate progress. They could sniff out problems early.”

SEPTA’s in-house team couldn’t define exactly what they wanted, because they didn’t know what that was until long into the process. The specifications for SEPTA Key required numerous rewrites and changes as new problems emerged. And the cycle continues.

The importance of having in-house technical expertise should come as no surprise to SEPTA. Whether it’s building new stations, separating tracks, renovating bus loops, rehabilitating bridges, replacing catenary wire, or installing $330 million safety systems, SEPTA tends to deliver on-time and on-budget.

SEPTA has a team of in-house civil engineers who can read blueprints and tell the difference between a truss and a trestle. But right now, at least at the higher levels of management, SEPTA has no one that can read code or tell the difference between an API and an SQL.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.