Why fish care about how much fertilizer you use

Fertilizers can become harmful to the environment if overused. (Stock photo)

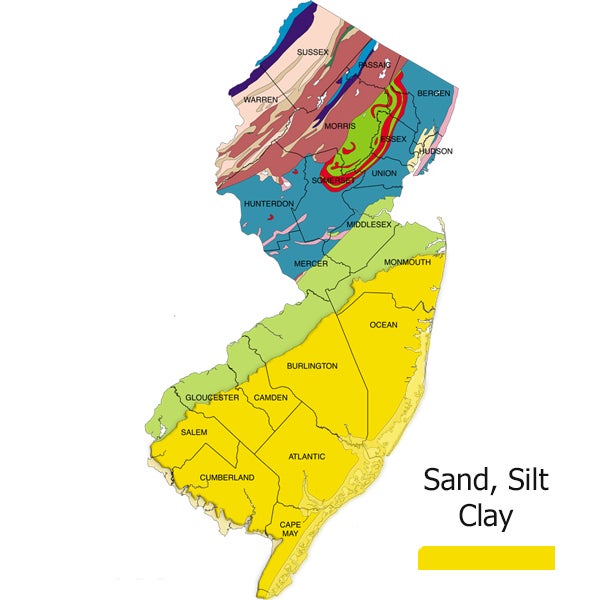

Fertilizers can help plants grow faster, stronger and healthier but, experts say, this can come at a cost to the environment. In many areas, Garden State soil is comprised mostly of clay or silt, but in South Jersey there’s a lot more sand mixed in.

Natural Resources Conservation Service (What the other colors represent)

While sandy soil has its advantages, like the fact that it warms quickly in spring and allows for an earlier harvest of crops, it can be a major headache for the at-home gardener. Because its particles don’t easily hold onto water and nutrients, the grasses and plants you’re used to seeing on manicured lawns (think hydrangeas and tulips and rose bushes) struggle to grow here.

For this reason, according to state soil scientist Richard Shaw, it’s “safe to assume people are applying more fertilizer in areas with sandy soil, in order to get the same level of productivity.”

This is a problem for two reasons. One, excess fertilizer can actually diminish the ability of soil to nourish plants. And two, fertilizers contain phosphorus and nitrogen. While plants need these nutrients to grow, sloppy application often means they end up on sidewalks and roadways. When it rains or snows, precipitation picks them up – along with other bacteria and pathogens – and flows into our storm drains.

NPK labels indicate the percentage of of Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium

Once the phosphorous and nitrogen hit a body of water, they continue doing their job. Only now, they’re not fertilizing your lawn, they’re fertilizing large blooms of algae. These blooms are responsible for creating a scummy surface that blocks sunlight, and for leaching oxygen from water, suffocating all living things.

While fertilizer wasn’t the only culprit, a hypoxic area was created off the New Jersey coast in 1976 resulting in a $500 million loss to the fishing industry. The area eventually recovered but hundreds of these oceanic “dead zones” still exist worldwide.

Tougher regulations

In 2011, Governor Chris Christie approved the most restrictive fertilizer law in the nation. The legislation increased public education opportunities regarding correct fertilizer usage, launched a certification program for professional lawn care providers, and required that fertilizer manufacturers reformulate their products to limit the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus. It also created a best practices guide that prohibits fertilizer application during winter months when plants are too dormant to absorb it, during or just before heavy rainfall, and within 25 feet of any water body.

While the law allows the state to fine lawn care providers as much as $500 for a first offense, fines for homeowners have been left up to municipalities.

NewsWorks reached out to the code enforcement offices in Atlantic City, Ocean City, Sea Isle, Avalon, Stone Harbor, Wildwood and Cape May to find out whether any homeowners have ever been fined.

At press time, only John Queenan of the Cape May office had responded. “I mostly monitor the professional landscapers, to make sure they have the proper license,” he said. “No homeowner has been issued a summons concerning misuse of fertilizer in Cape May. On the rare occasion someone complains that a neighbor’s fertilizer is damaging their plants, I will follow up to try and educate that person, rather than bring the hammer and take them to court, because many people just don’t understand.”

“The police aren’t tracking this,” added Zach Lees, policy attorney for Clean Ocean Action. “The onus is on the municipalities, and they’re already stretched so thin. Along with monitoring litter or the clean-up of dog poop, this type of ordinance often becomes the community’s responsibility. If you do a survey of retail locations, you’ll see these places are in pretty good compliance when it comes to the types of fertilizer being sold. But when it comes to what consumers do with the fertilizer once they buy it – whether they’re abiding by the best practices guideline – there needs to be more awareness.”

Case in point: the most recent integrated report from the DEP, published in 2014. Essentially a report card for New Jersey’s water, it shows that median concentrations of nitrogen increased statewide during a two-year assessment period. In fact, 98 percent of water in the state fails to meet water quality standards, and the major culprit is rainwater storm runoff.

The good news

Things might not be as desperate as they sound. Dr Susan Murphy of The Soil Testing Laboratory at Rutgers University said more people are testing their soil to see what nutrients are needed before blindly dumping bags of fertilizer on their gardens.

Oftentimes, they discover all that’s needed is a bit of organic material one can purchase at a nursery or compost in his own kitchen. “We educate the public on this fact,” she said. “When it comes to fertilizer, there can be too much of a good thing.”

Local solution

Also, native plants – which have adapted to sandy soil sans fertilizer– are starting to enjoy a renaissance, thanks to advocacy from groups like the Nature Center of Cape May, which just wrapped its annual native plant sale, and The Wetlands Institute in Stone Harbor, which will hold a similar event on May 21 and 22.

Despite their importance in preventing coastal erosion and providing habitat for wildlife, native plants like huckleberry, sassafras and the beach plum tree have historically been overlooked by New Jersey home landscapers. The notion of a manicured lawn as a status symbol took hold in the 17th century, when French and English castles were guarded by men whose vision couldn’t be obstructed by wild trees and shrubs. Eventually, this idea that grassy equals classy seeped into the American psyche. We’ve been opting for clean-cut vegetation bred for pretty colors and flowers ever since, and we’ve shunned the more motley looking plants that, tolerate salty gusts of air and nutrient-poor soil.

“It’s an institutional sort of thing,” said Chris Miller, Manager of the USDA’s Cape May Plant Materials Center, which evaluates vegetation for its use in conservation. “It’s amazing how much time we spend mowing and fertilizing and weeding and raking. It’s actually a lot of time wasted. People need to understand that lawns can be a smaller component of their current landscape, and they can still have an aesthetically pleasing property that’s also a functioning ecosystem.”

Now, the Plant Materials Center is conducting research trials focusing on legumes – a group of plants that produce their own nitrogen, which can then be utilized by neighboring vegetation. The end game is determining which plants are compatible with one another, in order to achieve a self-sustaining ecosystem – no chemical fertilizer needed. These results should be available in 2017. Shaw believes the solution starts with respecting our soil, and thinking about it in a new way, “Maybe we should stop calling it dirt.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.