Who killed the chemistry set? And an effort to reinvent it

ListenA Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit is seeking the next great science toy.

Jennifer Landry is opening an “atomic energy” chemistry set from the late 1950s.

She’s the director of the Chemical Heritage Foundation museum, which has the largest public collection of chemistry sets in the U.S.

The bright red Chemcraft set she’s holding is a mirror to the fascinations of its time. Bold letters aside dozens of vials of chemicals promise new experiments in “Modern Plastic,” “Outer Space” and “Atomic Energy.”

“What’s interesting is, it does have uranium ore in it, as well as a radioactive screen, so you’d be safe,” Landry said. “You have your radioactive screen, it’s OK,” she adds, laughing.

Remember the chemistry set?

If you’re of a certain age — say, a baby boomer — the answer is likely a warm and nostalgic “yes.”

.@zackseward Everything was great till foil anode hit can wall, shorting out transformer. Minor electrical fire, smoke, yelling Mom. 2/2

— Scott Hensley (@scotthensley) December 30, 2013

If not, you might be a little fuzzy on how a chemistry set even works. Or, simply unimpressed.

@ElinSilveous @zackseward @WHYYThePulse I don't- @cspmom loved hers but the modern ones have the exciting stuff removed for safety!

— jack andraka (@jackandraka) December 31, 2013

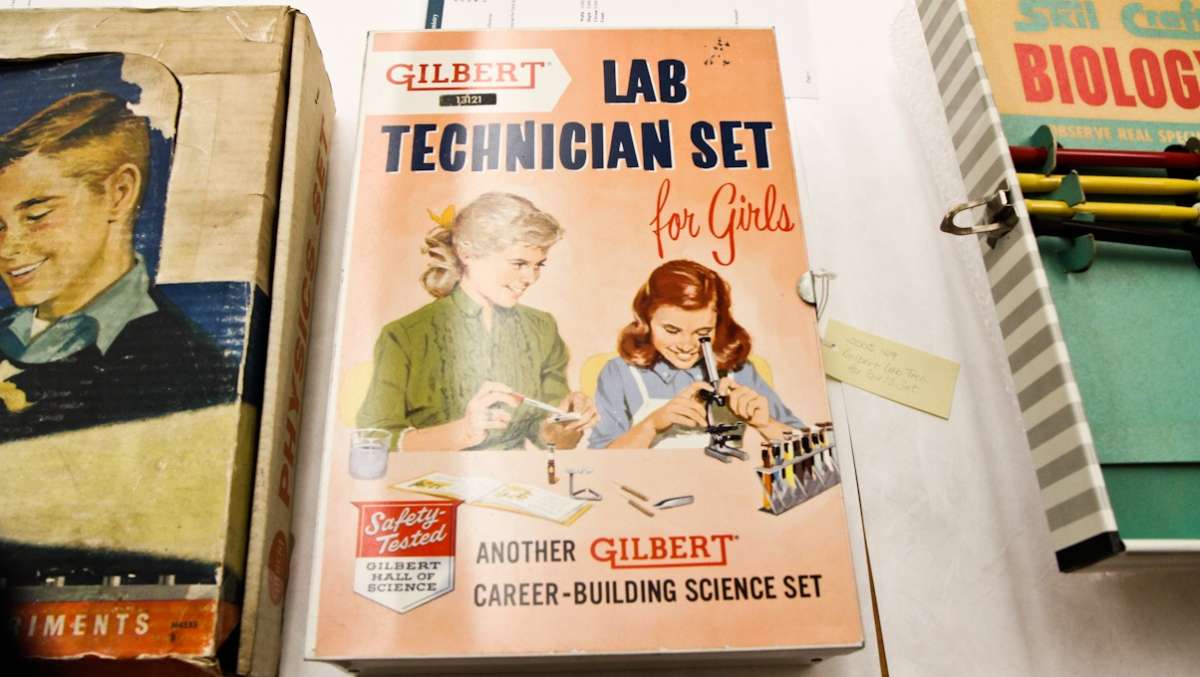

The CHF museum here in Philadelphia has over 100 chemistry sets — with uranium ore, polyvinyl chloride and all. They come with dangerous-sounding chemicals (and plenty of benign ones, too), small pieces of lab equipment, some instructions and a license to experiment.

On a recent Tuesday, Landry and her team have pulled a dozen or so sets from the stacks, including this one from 1917.

“It has a charming cover on it, with some children on it, experimenting,” she said. “They’re blowing something up on what appears to be the dining room table.”

Times change

Chemistry sets date back to the mid-19th century. The CHF collection includes a set from the 1850s, though it’s more targeted at university students than grade schoolers.

By the 1930s and ’40s chemistry sets as educational toys were gaining in popularity. Parents saw them as a launch pad for future careers in science; their children saw them as good fun.

But it wasn’t until after World War II that America’s love affair with the chemistry set really took off, says Landry.

Buoyed by a growing conviction that science meant Progress, chemistry was cool — to both parents and kids alike.

“If you were writing out your Christmas wish-list, the chemistry set was often one of the top items on the list,” said Landry. “That’s probably not the case today.”

The decline of the chemistry set started as early as the 1960s, Landry says.

“Public attitudes toward science changed; Silent Spring by Rachel Carson came out in the early ’60s; we became a lot more environmentally aware,” she said. “Then you also have this concern for safety, the rise of legal knowledge and concerns about lawsuits, and then just childhood safety.”

Times change. We move on. But the big picture has some in the science community concerned.

‘Reimagining the chemistry set’

Generations of scientists and engineers fell in love with science because of their childhood chemistry sets. (It’s even a fairly common trope in the obituaries of recently deceased Nobel Prize-winners.)

Making stink bombs and accidentally torching curtains actually served a purpose: letting children explore and innovate in a tangible way.

“Our SPARK competition is looking to find the next generation chemistry set,” said Rick Bates, interim CEO of the Society for Science and the Public.

His Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit is leading a new effort to recreate the magic.

In partnership with the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (Gordon is a co-founder of Intel), the SPARK competition is offering up over $50,000 in prize money.

The goal: Help launch the next great science toy.

“What we’re trying to do is to find the next idea that will help children explore and really discover things on their own,” Bates said.

Thing is, even SPARK acknowledges its winning toy probably won’t involve chemistry. (The project’s acronym stands for Science Play and Research Kit.) Bates says it’s the spirit of the chemistry set they’re going for.

Early submissions to the competition have run the gamut from immersive, scientific computer games to engineering projects made from household items, according to Bates.

The challenge is to leap the high bar set by the slew of high-tech, high-gloss devices in the hands of kids these days. Bates says most are “sealed black boxes,” nearly impossible to get inside and fuss around with.

“We want to provide something that matches that experience but allows them to tinker,” he said. Tinkering is key.

The SPARK competition is accepting applications until Tuesday, Jan. 7. Winners will be announced at the end of next month. And maybe, just maybe, the winning toy will one day be archived in a science museum.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.