What causes knuckles to ‘crack’?

ListenResearchers pull fingers and make a discovery.

It’s a sound that may make you cringe. Or as the perpetrator, may lead to unsatisfying relief or even hopes of feigned toughness.

Either way, it comes from that simple human act of clenching those fists or stretching those hands and…pop! Out comes a knuckle crack (or cracks, depending on one’s level of talent).

But what exactly causes that pop, that crack in the metacharpal felengeel joint?

Greg Kawchuck, a bioengineer and professor of rehabilitative medicine at the University of Alberta in Canada, says it’s been a bit of a mystery to scientists.

“It’s not terribly clear in the literature what actually happens,” he says.

Now he and a few other curious researchers are out with a new study, published in PLOS One, that could help demystify the process.

A point of disagreement

In the late 1940s scientists theorized that when the bones suddenly pulled apart, that crack came from a gas cavity that would form in the fluid in between those joint surfaces “in the same way you might have a gas bubble created when you open up a can of pop or soda,” explains Kawchuck.

But by the 1970s, researchers were headed in the exact opposite direction. They thought that “pop” came from the collapse of an already existing gas bubble when the bones quickly pulled apart.

So which process caused that crack? Scientists were limited in what they could actually observe because of the available imaging technology.

Why not put a scan on it?

Kawchuck and some colleagues then realized that no one had yet used modern technology to allow them to actually view this phenomenon up close, potentially putting this debate to rest.

So they immediately set up a study using a motion MRI machine. But for this to work, they needed the right test subject, a person “who could perform at showtime” and crack on demand.

They were in luck.

Kawchuck’s colleague, Jerome Fryer, who had the idea for this whole thing in the first place, turned out to be a world class knuckle-cracker.

“I mean, we’re calling him the Wayne Gretsky of knuckle cracking,” Kawchuck says, referring to the region’s local hockey hero.

Pull my finger…no, seriously

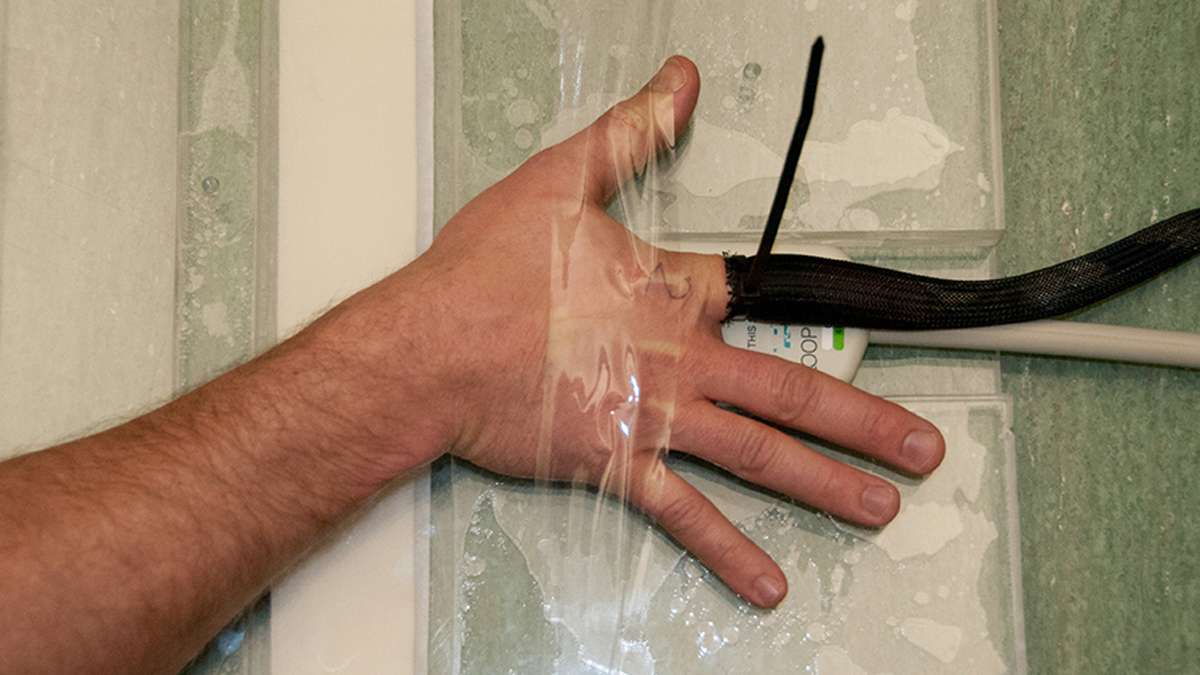

Kawchuck’s group then tied a rope to Fryer’s finger, which was all hooked up to the motion MRI. Then they gently pulled on that rope to make the knuckle crack. Although the MRI suite is loud, they could feel that crack through the rope, explains Kawchuck.

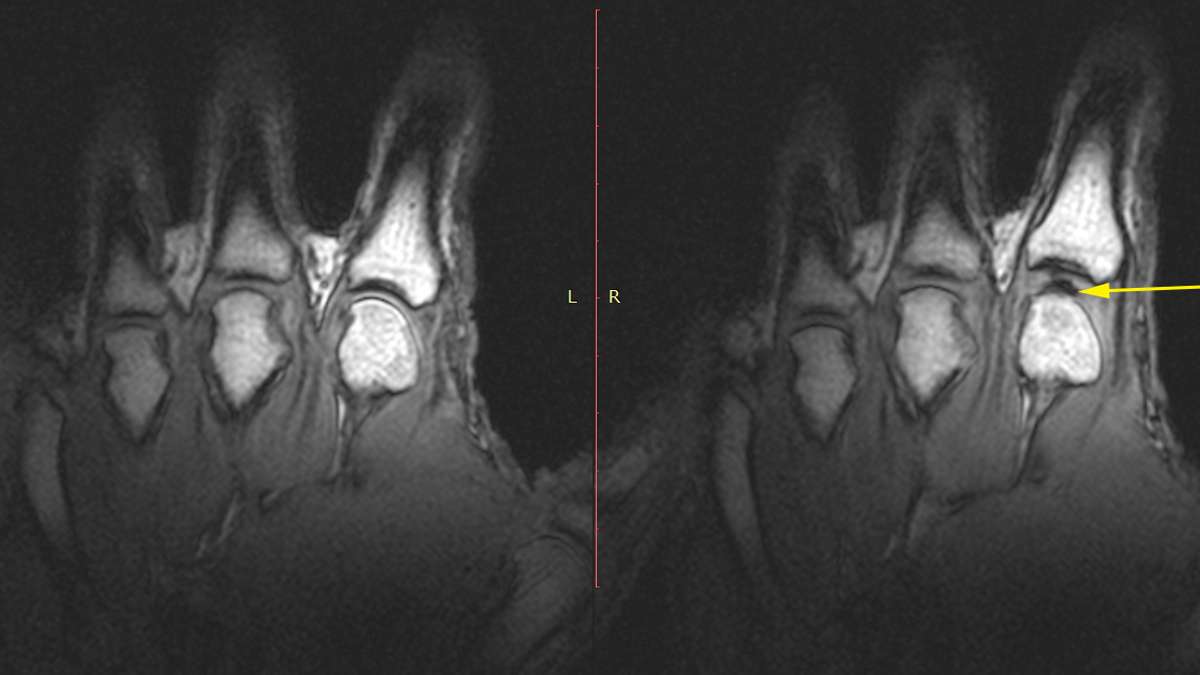

After, they reviewed what they saw in slow motion.

“Our jaws were on the floor. It was like, ‘Wow! we can’t believe what we’re seeing!'” says Kawchuck.

What they first saw was a white flash. Kawchuck thinks that’s the synovial fluid that lubricates the joints. Then as the bones pulled apart from that finger tug, “magically, we saw this black cavity form at the same time that the sound was produced.”

It was a gas bubble, and it stayed there after the crack.

To Kawchuck, this was evidence supporting that original theory that the knuckle crack was related to the creation, not the collapse of a gas cavity.

He also observed that cavity would form, even when they pulled on Fryer’s finger and it didn’t crack.

A new mysery

The unclear process behind this crack hasn’t seemed to keep chiropractors like William Lauretti, associate professor of Chiropractic Clinical Sciences at New York Chiropractic College and self confessed chronic knuckle-cracker, up at night.

“It’s not something I’m terribly concerned about,” he says. But he does find an important take home message from Kawchuck’s study.

“For years, that collapse of the air bubble was thought to cause damage,” he says.

Lauretti is specifically referring to marine equipment, in which engineers observed that the constant popping of air bubbles against propellers in water damaged the surface. It led doctors to wonder whether that process in knuckle cracking could cause similar damage to joints.

Other clinical research has since countered that assumption, finding that knuckle-cracking doesn’t appear to cause damage in chronic-knuckle crackers, but Lauretti says it’s to now know that “the pop doesn’t come from that collapsing. It’s reassuring to have further confidence that [knuckle-cracking] is not causing damage.”

Kawchuck says the real mystery now is why knuckle cracking does not seem to cause major joint problems or arthritis.

“It’s a lot of fun to do a study called the ‘pull my finger study,'” he says, laughing. “But in the end, we’re really hoping that it helps us understand why some joints remain healthy over time and others may not,” he says.

That, however, may require a lot more finger pulling.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.