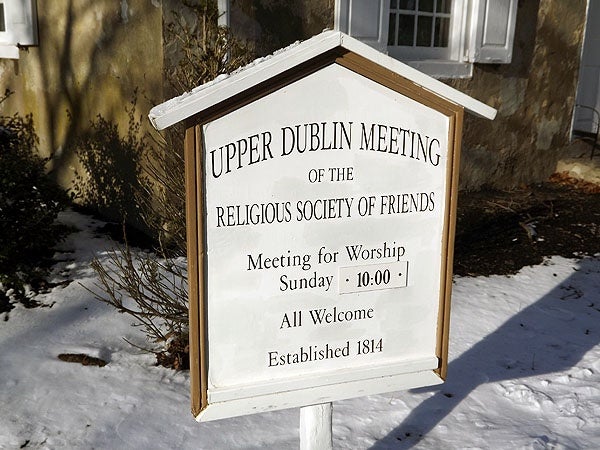

Upper Dublin Meetinghouse honors ancestors for Black History Month

-

<p>A wreath was placed to honor Hannah Atkinson and the unknown slaves who are also buried in the graveyard. (J. Woods/NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>McClinton posing with some of the descendants of Quaker abolitionist Hannah Atkinson who are still members of the Upper Dublin meeting. (J. Woods/NewsWorks)</p>

-

-

-

<p>Mavis Wanda McClinton, the first African American member of the Upper Dublin meeting, researched the history of the underground railroad site and organized the event along with members of the meeting. (J.Woods/NewsWorks)</p>

-

-

<p>Fugitive slaves who died on their way to freedom were buried in the cemetery in unmarked graves. (J. Woods/NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>In the mid 1800's those who died while escaping slavery on the underground railroad were buried at the cemetery behind th meetinghouse. (J.Woods/NewsWorks)</p>

-

-

<p>The small building was filled to capacity for the memorial. (J. Woods/NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Following the service visitors walked to the cemetary for a brief wreath laying cemremony. (J. Woods/NewsWorks)</p>

On a snowy Saturday about 100 people packed the Upper Dublin Quaker Meeting house to attend a memorial service commemorating the lives of fugitive slaves who died on route to freedom on the underground railroad and were buried in the meetinghouse cemetery.

Avis Wanda McClinton stood by the door of the Upper Dublin Quaker Meeting house, greeting everyone who entered with a handshake or a hug and a hearty “Hello, how are you? Thank you for coming!”.

On a snowy Saturday about 100 people packed the meetinghouse to attend a memorial service commemorating the lives of fugitive slaves who died on route to freedom on the underground railroad and were buried in the meetinghouse cemetery.

McClinton and the members of the meeting organized the event to raise awareness about the historical significance of the cemetery and to honor the “long forgotten fugitives slaves”.

The history of the meeting house and its association as a stop on the underground railroad began when Quaker Hannah Atkinson moved into the farm adjacent to the Upper Dublin meeting house which was built on a parcel of land donated by her ancestors. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Atkinson, an abolitionist, decided to defy the act of Congress and provide assistance to slaves escaping from the South, making their way to Canada. Her plan met with resistance from members of the Quaker meeting but Atkinson continued her work. When slaves died in their attempt at freedom, they were secretly buried in the meetinghouse cemetery. Because the underground railroad operations were illegal the graves were never marked.

McClinton is the first African American member of the Upper Dublin Quaker meeting. Honoring the history of the place and the people had special meaning to her. She said that the historical research and work necessary to put the memorial program together took “one year and four months” and was at times difficult and frustrating but once she heard about Atkinson and the remains of the fugitive slaves she felt compelled to do something to keep their memory alive.

During the emotional service McClinton remarked that the slaves were “buried in the dark of the night to give me the right to say ‘no’.” She thanked her ancestors for the sacrifices they had made to “allow me to live life like this”.

During the service a number of Hannah Atkinson’s direct descendants stood and spoke about their ancestor and about the importance of keeping the history alive. The memorial service drew many heartfelt responses from those attending. Among those crowding the meetinghouse were representatives from Mothers in Charge, member’s of McClinton’s family, relatives of Hannah Atkinson, officers from American Legion post 769, residents of Foulkeways senior community, area neighbors and member from numerous local churches and meethinghouses.

While the names of the enslaved people are unknown, McClinton and members of the meeting are working to gain permanent recognition for the site with an historical marker.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.