Tourism in Newark, New Jersey? 50 years after riots, city says it’s time

Tourism in Newark? You might not think of it as a destination, but boosters say Newark is ready for visitors as part of a comeback.

A company called Have You Met Newark? has taken more than 2,000 visitors on walking tours and bar crawls. Tour company founder Emily Manz points out everything from Nasto’s ice cream parlor , made famous in an episode of “The Sopranos,” to a church, St. Stephan’s, that appeared in the movie “War of the Worlds.”

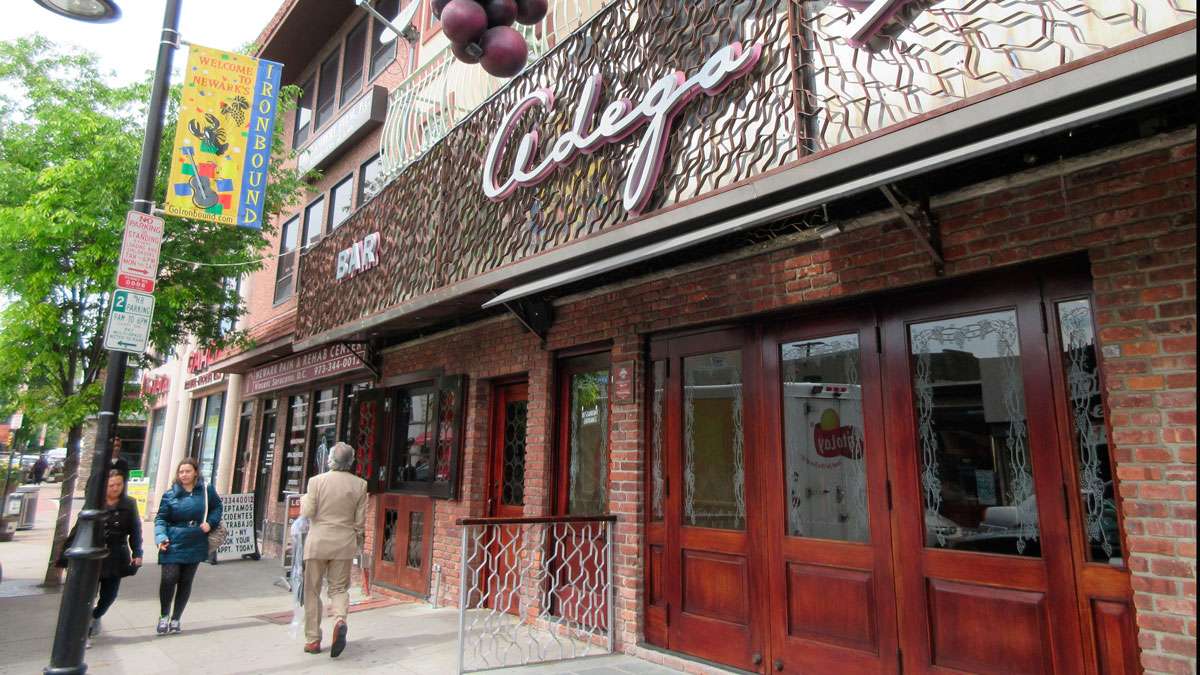

The Greater Newark Convention and Visitors Bureau has started taking travel writers to see attractions like the Newark Museum and the Ironbound, a neighborhood known for Portuguese and Spanish restaurants and shops.

And in August, the “100 Things to Do Before You Die” series will publish a Newark guidebook written by Lauren Craig, who fell in love with Newark while attending Rutgers Law School and calls herself the city’s “glambassador.”

And in August, the “100 Things to Do Before You Die” series will publish a Newark guidebook written by Lauren Craig, who fell in love with Newark while attending Rutgers Law School and calls herself the city’s “glambassador.”

But this summer also marks 50 years since riots scarred the city.

“The perception of Newark being unfriendly, dangerous, dirty is something that has been ingrained in people for many, many years,” Craig said. “I fight against that every day.”

HAHNE & CO., A SYMBOL OF REBIRTH

Officials point to a massive brick building, vacant since the Hahne department store closed in 1987, as a symbol of Newark’s rebirth. The Hahne building reopened this year with apartments (one-bedrooms rent for $2,000 monthly) and businesses, including a Whole Foods. Celebrity chef Marcus Samuelsson plans a restaurant there. An arts incubator, Express Newark , hosts workshops and exhibits onsite, including a jazz history show organized by Rutgers University’s Institute of Jazz Studies.

On a recent day, another downtown gem, Military Park , was busy with kids riding a carousel, a jazz band playing and the after-work crowd mingling at a trendy park eatery, BURG.

Newark is holding more events to attract people to the public areas. (Alan Tu/WHYY)

“I’ve been waiting for this,” said Jeremy Johnson, executive director of Newark Arts, as he surveyed the scene in the park. “No one is asking me if the National Guard is going to protect them when they come to Newark. They asked me that 20 years ago. So this is the dream.”

ATTRACTIONS AND HOTELS

Destination Newark has a lot to offer: New Jersey Devils hockey games and more at the Prudential Center , concerts and shows at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center and Newark International Airport, among America’s 20 busiest airports.

Newark Penn Station is also just 20 minutes from Manhattan via PATH, NJ Transit or Amtrak trains. That makes Newark a viable lodging option for visitors to New York City. Downtown Newark hotels include the historic Robert Treat , which has hosted four U.S. presidents; the Hilton at Newark Penn Station , popular with airline crews; and the Indigo boutique hotel. Rates for a July Sunday night at the Newark Indigo were $136 compared with $209 at the Indigo in Manhattan.

Treasures at the Newark Museum, a 10-minute walk from Newark Penn Station, include an 1885 mansion called the Ballantine House , a room of paintings by Joseph Stella, a Tibetan altar visited by the Dalai Lama and impressive collections of Native American and African-American art. “I go there as much as I can,” said Hrag Vartanian of Brooklyn, New York, editor-in-chief of online arts publication Hyperallergic.com . “But it’s amazing to me how many people have never heard of the Newark Museum.”

Before hopping the train back to New York, Vartanian heads to the Ironbound, where dining options range from old-school bacalhau at Seabra’s Marisqueira to tapas with a hipster vibe at Mompou .

The Ballantine House and the Ironbound are featured in Craig’s “100 Things to Do in Newark Before You Die” book, too. On a recent day, she also took a visitor to the Off the Hanger boutique , where “Newark Vs Everybody” T-shirts are prominently displayed; the Jimenez Tobacco cigar lounge and bar; Casa D’Paco , an Ironbound restaurant; and Gateway Project Spaces , an art gallery adjacent to Newark Penn Station.

At one point on Craig’s whirlwind tour, a taxi driver disputed the idea that Newark was ready for tourists.

“I beg to differ,” Craig said politely, then said to a guest, “You see what I’m fighting against?”

THE CITY PAST AND PRESENT

Of course, problems persist. Newark’s population declined from 400,000 in the 1960s to 280,000 today. Thirty percent of residents live in poverty. Crime remains a top concern, though it’s decreasing: Newark is statistically safer than Washington, D.C., Atlanta and Memphis, Tennessee.

But Newark’s decline in the last half of the 20th century wasn’t isolated. Many urban areas lost population as factories closed and white middle-class Americans fled to the suburbs. Even Newark’s riots were part of a larger pattern: Riots rocked more than 100 cities in 1967, and many — including Newark’s, which erupted after the arrest of a black cabdriver — were sparked by allegations of police brutality amid racial inequality and lack of opportunity in African-American communities. More than 20 people died in Newark’s riots; millions of dollars in property damage was sustained.

Karin Aaron, CEO of the Greater Newark Convention and Visitors Bureau, left the city in the early ’90s because she “didn’t see any progress,” even though her mother often spoke about “how great Newark used to be.” Aaron moved back in 2016 and believes a renaissance is underway, saying: “Everybody loves a comeback story.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.