The federal rule holding back neighborhood-scale mixed-use buildings

An example of mixed-use development on N. 2nd Street in Philadelphia's Northern Liberties neighborhood. (PlanPhilly file image)

Efforts to promote more neighborhood-scale mixed-use buildings typically focus on local policy changes, but there may be an event bigger obstacle than local zoning: the federal government.

A new paper from the Regional Plan Association, “The Unintended Consequences of Housing Finance,” sheds some light on the ways federal financing rules discriminate against mixed-use infill development at a time when more Americans are voting with their feet for compact cities and older downtowns. Developers often allude to financing issues as a reason for requesting zoning variances for more height and density, but the particulars aren’t always well-understood by the public.

The issue is this: in the name of limiting their exposure to risk, federal lenders like the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac all place regulatory limits on the amount of non-residential space a building can have, as a condition for receiving federal financing or federal loan guarantees. Compounding the problem, the federal standards also influence the private lending standards at private financial institutions.

To qualify for federal financing, developers need to keep the amount of commercial space, or the amount of revenue from commercial space, below a certain percentage — between 10-25 percent, depending on the lender.

The report’s authors argue that these caps are set too low for neighborhood-scale commercial buildings to qualify, “effectively disallowing most buildings with less than five stories and in some cases making even seven-story buildings non-compliant.”

“By capping the amount of commercial development permitted in federally-backed mortgages and programs,” they write, “the rules make it hard to finance construction or renovation of three-to-four story buildings in many mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods.” The criteria many private lenders use for assessing risk is based on the feds’ criteria, the report explains, so many projects not seeking federal financing or loan guarantees are indirectly affected. One reason private banks do this is because loans for relatively straightforward developments like single-family homes can more easily be securitized and resold on the secondary market. By contrast, mixed-use infill or redevelopment projects are rarely so cookie-cutter, and remain parked on banks’ balance sheets as “non-conforming” loans. From the report:

“Developers believe there is a “lack of understanding within the financial community” when it comes to financing mixed-use projects. Developers have a difficult time explaining why their non-conforming project is a good investment, even when it has been demonstrated time and again that these types of developments are in high demand. As major banks often won’t make the loans, a tenacious developer might find financing with a smaller, community bank. In practice these projects would be good investments, but require time and openness from the lender, and an interest in supporting the local community. Yet as there is no secondary market for mixed use loans, they are held on the bank’s balance sheets, keeping the bank from “reusing” the funds for other loans and collecting more fees. Including these opportunity costs, the loans are notably more expensive for the bank, and thus expensive to the developer.”

The Regional Plan Association (RPA) report argues that the current federal standards provide an unintended shot in the arm for a range of damaging trends, many of which the federal government is at least nominally committed to reversing. By tilting the market so far toward single-family homes (the recipient of 81 percent of federal financing,) government lending standards discourage investment in older urban areas and distressed communities, reinforce clusters of poverty, and promote auto-oriented land use patterns that increase driving and energy use while reducing physical activity.

They also promote anti-urban design, by pushing developers toward larger projects that achieve the right ratio of residential to commercial space, but which may be “bigger and bulkier, with set-backs and other design features that may reduce neighborhood vitality and the viability of commercial activity…”

The federal lending standards were first developed in the early 1930’s when mixed-use and multifamily mortgages were considered financially riskier than those for single-family homes. RPA argues this thinking is outdated, pointing to 2013 research from Fannie Mae finding mortgages for properties with high marks for walkability, transit access, and energy efficiency were actually less likely to default than traditional mortgages.

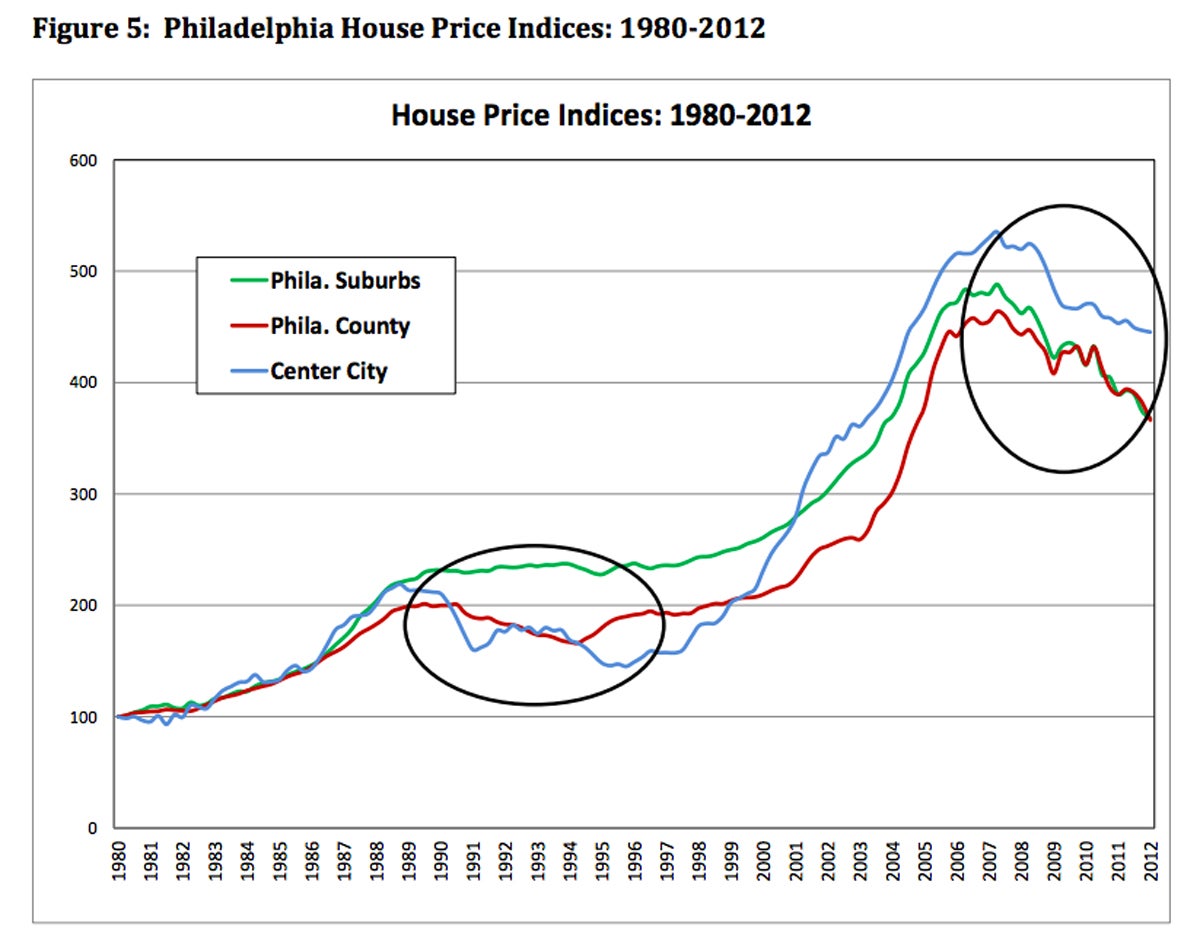

Similar research by economist Kevin Gillen in 2012, conducted for the Congress for New Urbanism, compared relative price declines in different areas of the Philadelphia metro area during the recent downturn, and reached similar conclusions, showing “that homes in communities with New Urbanist characteristics have, on average, performed much better during the recent U.S. housing downturn than their counterparts in lower-density, single-use, exurban and auto-oriented communities.”

While urban areas took longer to recover in the 90’s, more recent shifts in living preferences allowed Center City Philadelphia housing prices to hold up better during this downturn. (Chart by Kevin Gillen)

But even though the federal government has recognized these unintended outcomes, and is beginning to grapple with this updated risk assessment, RPA says HUD is still soft-pedaling on solutions. HUD recently proposed relaxing one of the non-residential limitations for one of its programs and also recommended giving regional administrators some limited flexibility to waive standards for particular projects under certain conditions. The report’s authors doubt these changes would significantly increase the number of qualifying urban projects though, or crucially, influence the private lending market. What changes do they recommend the federal government make, specifically?

Raise non-residential caps on loans to mixed-use projects

RPA suggests “[r]aising the non-residential limits to at least 35 percent but under 50 percent,” or lifting them altogether, which it says “would allow three-story mixed-use buildings to be financed,” and “allow the private financing market to better meet market needs and preferences, and determine the risk and cost associated with different projects.”

At the Strong Towns blog, Charles Marohn raises the point that while a cap of 50 percent on non-commercial area would go a long way toward unlocking renovations of mixed-use buildings in the eastern United States, Midwestern cities tend to have a lot more two-story mixed-use buildings that would still be left out. Mitigate risk in other ways

Rather than a hard cap, the authors recommend more flexible alternatives like shorter loan periods, so loans can be rolled over more frequently; requiring supplementary or secondary mortgage insurance for the first few years of a project; or insurance against vacancy rates exceeding a predetermined level.

Create a secondary market for mixed-use loans Noting that private lenders’ behavior is shaped in large part by opportunities for securitization and resale of loans on the secondary market, the authors suggest “creating a mixed use loan asset class and otherwise stimulating the market for sale of such loans and bonds.” Raising the cap on non-residential space would make lots of non-conforming loans into conforming loans, remedying the problem, but they point out that even without this, Fannie and Freddie could “define a new category for mixed-use loans and begin to purchase them, such that a market for ‘quasi-conforming loans’ is created.”

Pilot finance reforms in Promise Zones and redevelopment focus areas

There are lots of urban places where the federal government is already working to stimulate more private investment, particularly mixed-use investment, via Promise Zones and other programs. RPA points out that these would be natural places to start testing some of these ideas before expanding them to the nation at-large.

If lifting the cap on non-residential space is too radical of a first step, the report also lists a variety of narrower kludges, variations, and half-measures that could also be deployed unilaterally by federal housing regulators.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.