The Amazing World of Brian Selznick at the Delaware Art Museum

There’s a little magic, but no slight of hand taking place at the Delaware Art Museum. Brian Selznick is the magician.

Brian Selznick is in the business of wonder. He creates books that challenge our notions of how fiction is supposed to work. Some say the trailblazing artist and storyteller has reinvented the genre, combining elements of the picture book, graphic novel, and film into entirely original reading experiences.

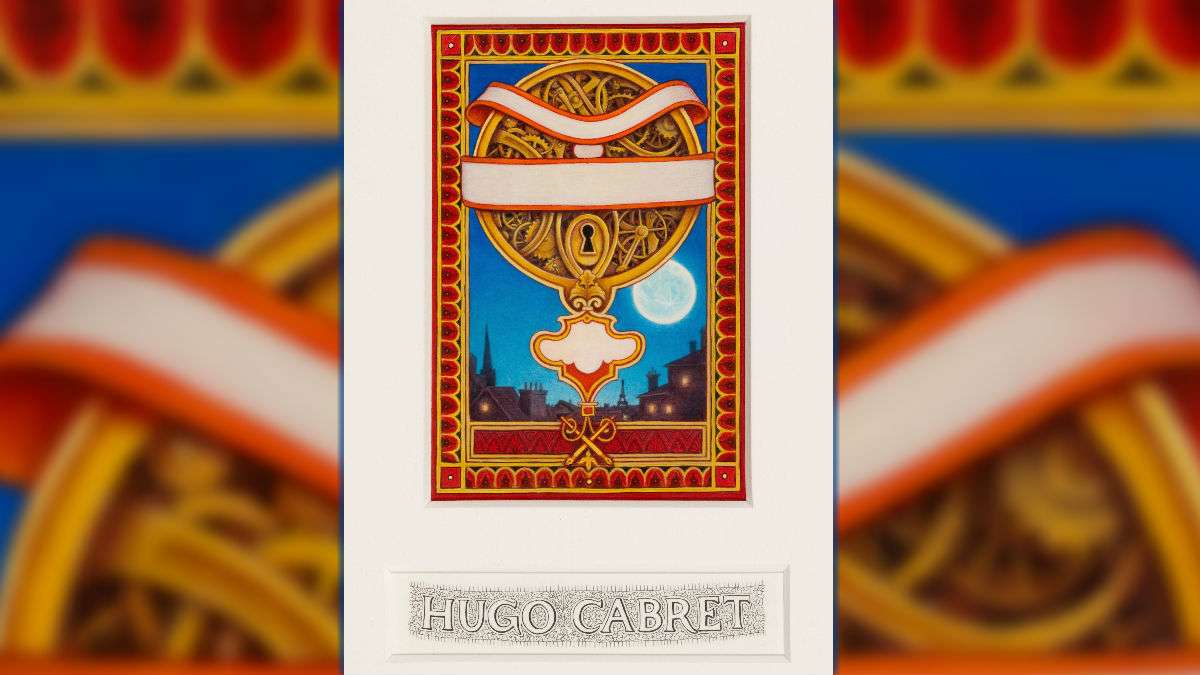

Selznick’s books introduce an innovative strategy for blending words and images, interweaving narrative and picture sequences. His breakthrough 2007 novel “The Invention of Hugo Cabret,” tells two sides of a single story about a little orphan boy, scrappy and clever, living in a Paris train station at the dawn of the 1930s, who forges an unlikely friendship with the pioneering French filmmaker Georges Méliès.

Hugo unfolds like a silent movie, with entire chapters told in mesmerizing pencil drawings. It is a book about magic– the magic of the silver screen, the magic of family and friendship, the magical thrill of adventure, all set in the City of Light. With its cinematic feel and magical take on historical fiction, the hefty book (526 pages, nearly 300 are picture pages) set the literary world on fire, winning the 2008 Caldecott Medal, and was also a National Book Award finalist. The transformative novel was turned into the five-time Oscar award-winning film “The Invention of Hugo Cabret,” directed by Martin Scorsese.

Fans of Selznick’s work can see it on a larger scale in the traveling exhibition “From Houdini to Hugo: The Art of Brian Selznick,” which runs through January 11, 2015 at the Delaware Art Museum. Hugo might be Selznick’s most recognizable work thanks in part to Scorcese’s adaptation, but he’s also the mind behind 18 other children’s books including “The Houdini Box,” “Walt Whitman: Words for America,” A”Amelia and Eleanor go for a Ride,” and “The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins,” and Frindle.”

Selznick’s illustrations animate the imaginations of children and adults with his blending of illusion, history, and adventure. The traveling exhibition presents more than 100 paintings and drawings by Selznick as well as books, so visitors can put the work in context.

“People want to actually see the original pieces of paper I touched, those drawings will be hanging on the walls as opposed to what they see in the published book,” Selznick explained. “The pen marks, the smudges what I may have spilled on the paper. These are true touchstones, in every sense of the word.”

Visual art pedigree

Brian Selznick, now 47, was born in East Brunswick, New Jersey where as a youngster he erected a house for trolls in a thicket behind his house. His schools offered a solid art program which Selznick supplemented with additional art lessons. Looking for a serious visual pedigree? His grandfather was a cousin to David O. Selznick, producer of the original King Kong and Gone with the Wind.

Selznick displayed his family’s gift for the visual arts. He attended the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design and nearby Brown University where he studied set design and worked at illustration next door at RISD. He was encouraged to write and illustrate children’s books. He resisted. Selznick’s focus was to become a set designer for the theater.

A position designing window displays at a Manhattan children’s bookstore, Eeyore’s Books for Children, opened Selznick’s eyes to the world of children’s literature. He began writing and drawing “The Houdini Box,” about a boy who almost meets the great magician. The book was published in 1991. Selznick subsequently illustrated novels and picture books for other writers, such as “The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins” that in 2002 won a Caldecott Honor. It is awarded annually to the artist of the most distinguished American picture book for children.

Today, Selznick’s worlds of imagination are concocted at his art studio stuffed with sculptures, hand-crafted puppets, and dioramas. Dividing his time between New York City and San Diego, Selznick travels as often as his book research requires.

Houdini a Hero

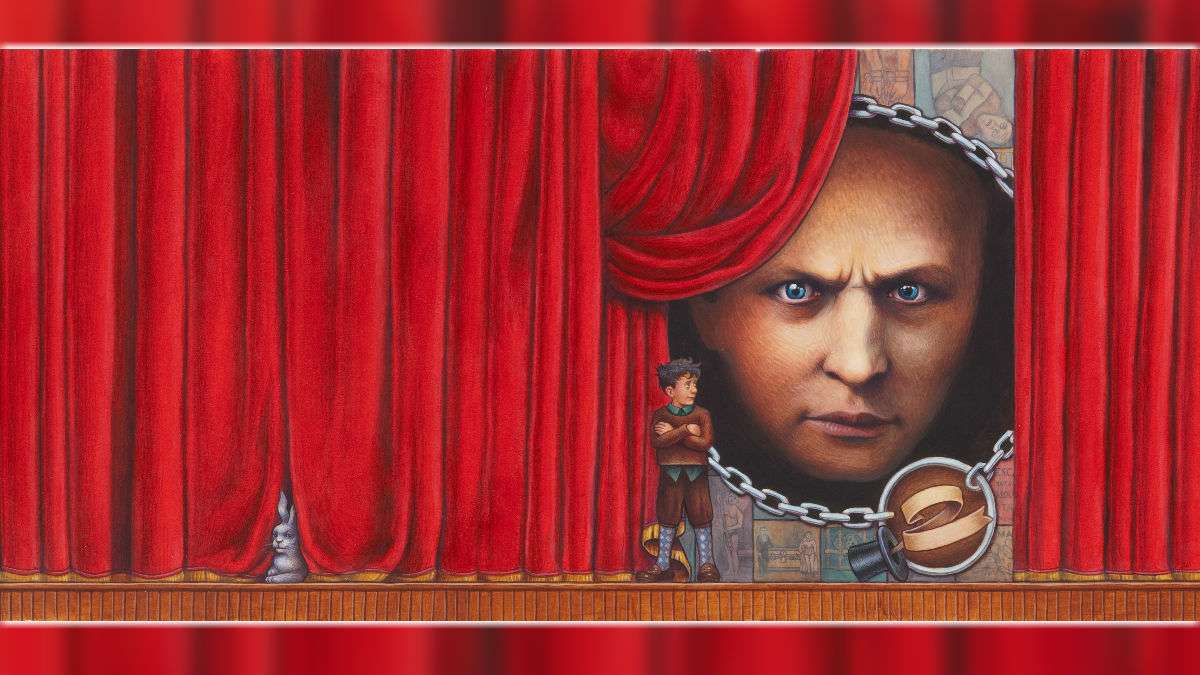

One illustration that grabs visitors immediately is the lush, dark cover for “Houdini’s Box.” It’s done in acrylic on watercolor paper, but the interior illustrations were done in pen and ink, some with random doodles around the edges.

Selznick painted Houdini’s stern face with piercing eyes emerging from behind a rippling red velvet curtain. The dead-on look on Houdini’s face, vaguely reminiscent of the floating wizard’s head in “The Wizard of Oz,” is both whimsical and creepy, something that Selznick created unabashedly in many of his book illustrations.

“Houdini was my hero, very meaningful to me as a kid,” Selznick related. “”Part of Houdini’s power is what we project on him, the ability to escape from anything. We all have that on a primeval level. It was a challenge to create that penetrating gaze that scary, disturbingly strange look through his eyes. Through his eyes you feel his real presence.”

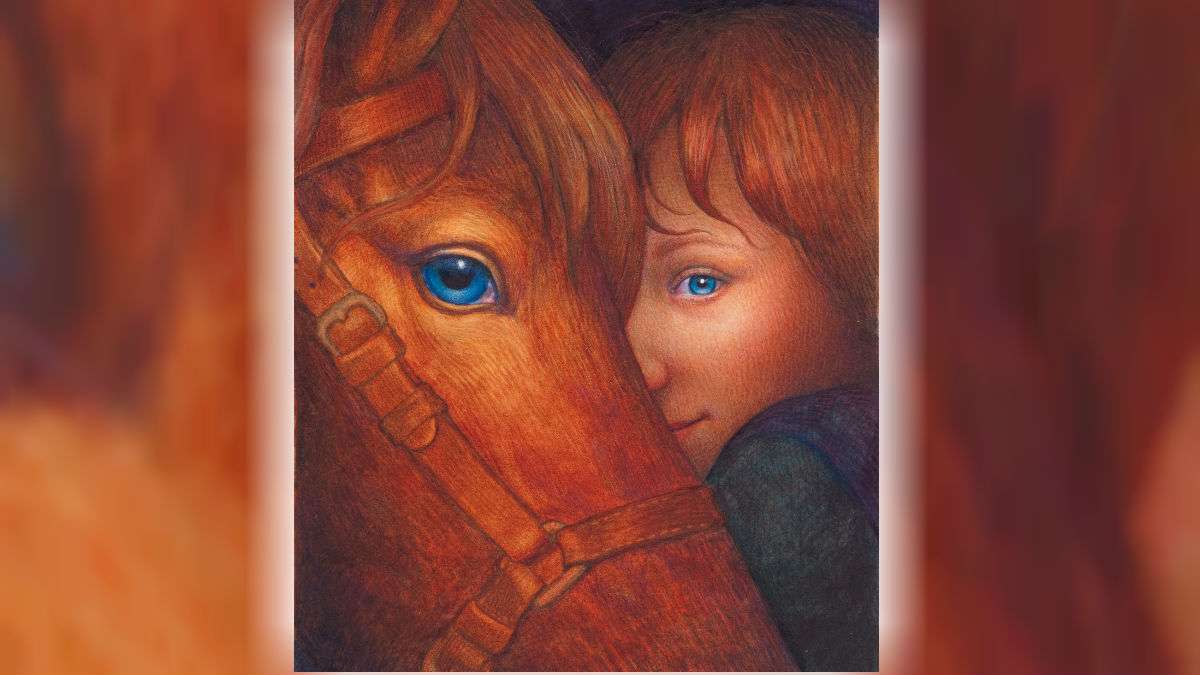

Vivid characters, raw emotion

Selznick calls himself a mechanical worker who doesn’t think about themes so much as plot. His remarkable drawings of vivid characters and raw emotion develop slowly over hundreds of pages achieved by painstaking cross-hatching drawing technique. He works with on a very small scale with a Staedtler Mars Pencil HB mechanical pencil.

“I’ve always cross-hatched, I have a copy I did of a Leonardo angel when I was ten, and later it was the Star Wars characters,” Selznick related. “It was proto-cross hatching, I didn’t even know it. Part of what I was doing in Hugo was to get the tone of black and white early French film. There was this richness in the textures of early cinema – conveyed on paper by the cross-hatching. It’s a way to achieve a certain kind of shading I want. I like drawing light, but of course to do that, you are drawing darkness.”

So how does he get those close-up faces, and above all startling eyes, that move through all those pages?

“I read that Dickens used to have a mirror on his desk and made facial expressions into it to help him describe what he saw,” he noted. “I keep a mirror to help me – I furrow my brow, I raise my eyebrows. So I guess I’m in good company.”

While he respects and appreciates computer generated art, Selznick says it erases the hand of the artist.

“I wanted to do something in which you see the hand of the artist,” Selznick explained. “I wanted to stretch as far as possible what I could do with the technology of bookmaking to achieve authenticity. I’m interested in the act of turning a page, to tell a story by moving forward physically. In picture books, you turn a page at the pace you want.

Unlike a film, you can go back or skip ahead, whatever you want to do. The reader become the driving force behind the narrative. It’s a more personal relationship in how you receive the story.”

——

Terry Conway writes about arts and culture throughout Delaware and the Brandywine. You can read his work at http://terryconway.net/cms/. You can write him at tconway@terryconway.net This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it .

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.