Special Report: How the city serves Eastern North Philadelphia

The handball court on the 2300 block of N. 5th Street is not much to look at. Weeds grow out of cracks in the pavement. The tiny playground beside the court – little more than a tire swing and some busted play equipment – is smeared with graffiti. At night, drug dealers swarm over the poorly lit park.

But for a lot of kids in this section of Eastern North Philadelphia, this broken patch of asphalt is all they have. It is a half mile walk to the nearest public recreation center from most points in this neighborhood, and a half mile trek to a decent park.

In January, PlanPhilly will publish the last in a series of reports on the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha and its role in Eastern North Philadelphia’s revival.

The final report will cover the experiences of the area’s residents

The writing, video and photography that comprise this series is made possible by a grant from the William Penn Foundation.

By most any standard, Eastern North Philadelphia is a service desert, a section of the city where basic amenities – such as parks, rec centers, libraries and fire and police stations – are few and far between.

In the past, the shortage of city services in this neighborhood arguably made sense. Residents had fled in droves, leaving behind blocks of empty homes and vacant yards, more than 2,000 abandoned in all, as of 1998. Now, though, Eastern North Philadelphia is one of the city’s most rapidly redeveloping neighborhoods, due in large part to the work of Asociación de Puertorriqueños en Marcha, or APM, a local community development corporation and social services non-profit.

With the recovery has come an increasing clamor for the kind of community services that some more affluent neighborhoods take for granted, like well-maintained parks, and facilities for public meetings.

“There’s a clear understanding that there are some gaps in the community,” said Jennifer Rodriguez, the APM vice president for programs. “In terms of youth and children and recreation facilities, there seems to be a general understanding that something needs to be done.”

The residents of Eastern North Philadelphia are not just imagining inequities. There are in fact relatively few parks and recreational facilities in their neighborhood according to a PlanPhilly analysis of city services and basic private sector amenities like grocery stores and hospitals.

The analysis reveals poorly served patches scattered all over the city. For instance, Port Richmond is miles away from the nearest city health clinic. Rec centers are scarce in the Walnut Hill and Spruce Hill neighborhoods of West Philadelphia. The blocks north of Temple University are over a mile from the nearest public library, and so are the neighborhoods of Belmont and East Parkside near Fairmount Park.

PlanPhilly’s targeted analysis of walkable service access in Philadelphia was completed by compiling more than a dozen data sets with the help of Penn’s Cartographic Modeling Lab and PennPraxis. PlanPhilly limited its analysis to the city’s central core and the densest sections of West Philadelphia. The interactive graphic ranks access to basic amenity groups and displays the walking distance to the locations of services.

The mapping, which was completed with data gathered by the University of Pennsylvania’s Cartographic Modeling Lab and Penn Praxis, revealed some distinct service patterns. The residential neighborhoods of Rittenhouse Square, Society Hill and Queen Village tend to have the easiest access to city services and basic amenities, while Southwest Philadelphia tends to have the least access.

“In under privileged, distressed neighborhoods like Eastern North Philadelphia there’s often a lack of amenities that other sections of the city have,” said Sarah Sturtevant, of the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, a national non-profit organization that aids CDCs and other neighborhood groups.

An interactive graphic showing service access in Philadelphia. Story continues below….

It is tempting to chalk this up to politics: affluent neighborhoods used their clout to get better access to city services. And maybe that is what happened. But if so, little of it was done on the watch of the city’s current elected leaders. Most of the facilities were built decades ago. Some date back nearly 100 years. Veteran city officials say there is little evidence that the systems – from libraries to rec centers to fire stations – were built out based on any comprehensive strategy, which may help explain why some neighborhoods have so many parks and rec centers, and others have so few.

“There was no plan, that’s for sure,” said Michael DiBerardinis, Commissioner of the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation, as he described the “hit and miss” expansion of Philadelphia’s network of recreation centers following World War II.

Children play ping pong at the playground located on 8th and Diamond Streets in Eastern North Philadelphia.

Yet, despite the lack of long-range planning, the city’s service network arguably offers reasonably comprehensive coverage. While the mapping certainly shows that some neighborhoods lack easy access to some services, no residential neighborhoods covered by this analysis are completely shut out of access to all services.

For instance, Eastern North Philadelphia may lack nearby libraries, police and fire stations, and quality recreation facilities, but it is well-served by a pair of public elementary schools and a SEPTA regional rail station.

“We have assets, as well as gaps,” Rodriguez said. “We’ve tried to work with what is available, and build off that.”

Given the city’s stark budget realities – which include a capital-spending program that is barely large enough to maintain existing facilities, much less build new ones – there is little chance that under-served neighborhoods like APM’s will be graced with new city service centers anytime soon.

But APM’s experience demonstrates that there are ways for CDCs and other organizations to fill in the service gaps, at least somewhat, that are created by distant city facilities.

“You have to be creative,” Rodriguez said. “I think one of the things APM has done well is identify community needs and look for partners and funders, not just the city, that will help us meet that need.”

Playground is a diamond in the rough

It takes only a few minutes talking to Kyirah “Kiki” Beckham to understand why residents of Eastern North Philadelphia rate parks and recreation as such a critical need.

The sixth grader has developed a nice jump shot and a mean crossover move on the blacktop of the 8th and Diamond playground, a few blocks away from the handball court. The two facilities are the neighborhood’s only public recreational spaces.

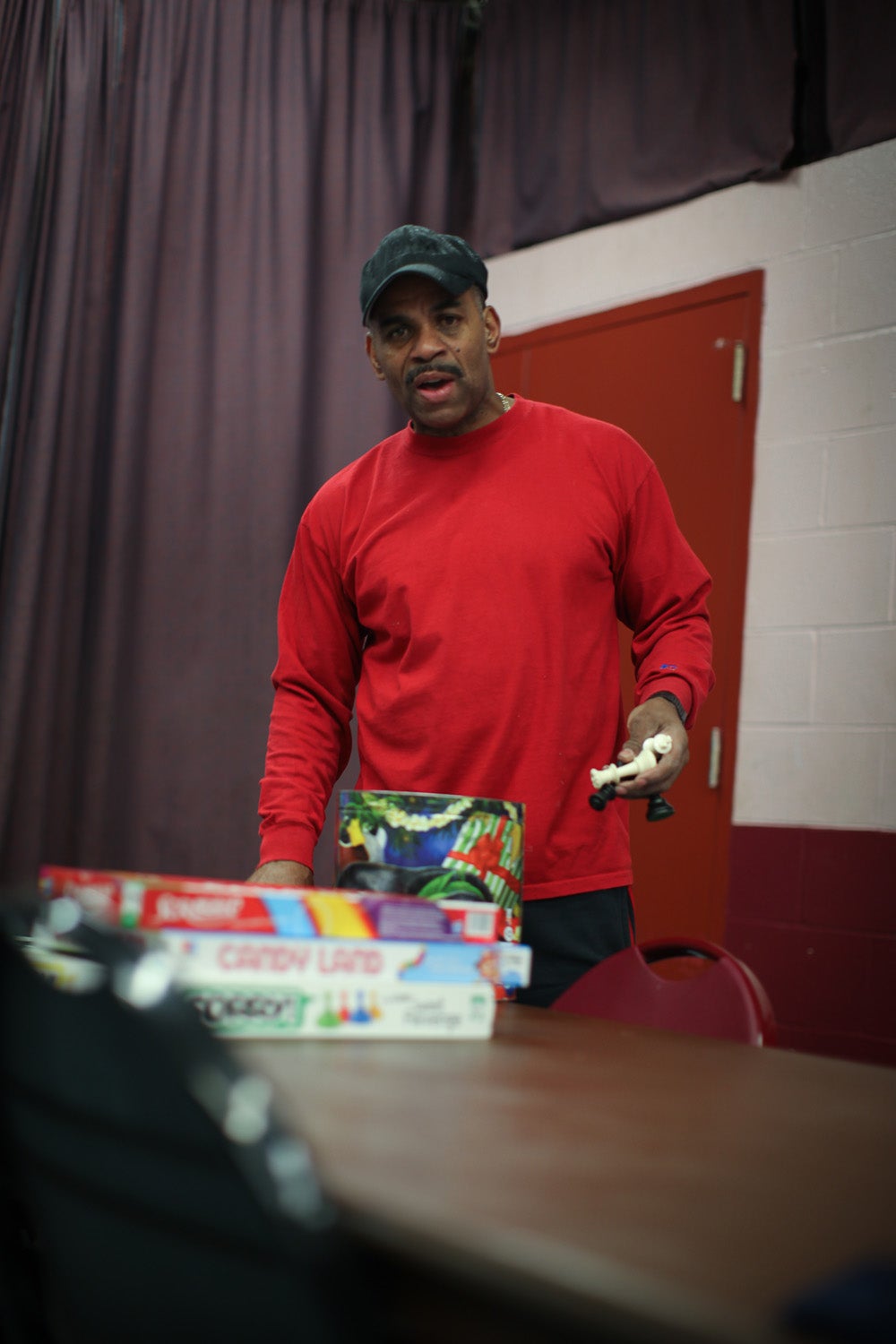

Kiki has been coming to the playground, which hosts a $5-a-week after school program in a tiny cinderblock building on the north end of the facility, for as long as she can remember. It is not a rec center, not as far as the city is concerned, given that it has no pool, no indoor basketball court or gym, nothing, really, except for a few dumbbells, a ping pong table, three aging computers and a couple of board games like Candyland.

But to Kiki, this modest playground has been an anchor.

“This rec center is real special to me. What can I say. I come here because it’s everything to me,” Kiki said.

She said it’s a place to get help with homework, to run around, to be in the company of friends. When talking about the place, she is so serious that her companions laugh at her.

“Everything about it, every little bit of it is just special, and I love it here. It’s everything. I’m serious,” Kiki said.

Dana Clark, the director of the playground, walks through a snowy basketball court while wearing his coaching jacket.

On Saturdays, the small building hosts a program for recovering addicts. On Sunday, a local church holds its services there. When it’s not booked for a regular program, residents will often use the facility for a baby shower or family reunion. In warmer months, about 200 kids take part in the playgrounds basketball league.

“It’s a real small facility, but we do a lot of big things with it,” said Dana Clark, a part-time city worker who manages the facility. His wife, Jackie Clark, runs the after-school program. “I wish we could do more.”

The facility, though, is maxed out. Clark and his wife serve about as many kids – 20 regulars, in the after-school program – as the tiny space allows.

But APM and other neighborhood groups have realized there is the potential to do something more with the forlorn handball court a few blocks east.

It was built in the 1980s at the urging of a long defunct neighborhood organization. The city technically owns the land, but it has never maintained the property: that job was supposed to belong to the dissolved neighborhood organization. In the years since the group disbanded, the park went to seed, despite the efforts of a handful of residents who still try intermittently to clean it up on their own.

Officers in the 26th Police District had long considered the park a nuisance spot and a haven for drug dealers. At a meeting of community groups organized by LISC – which is helping APM develop a comprehensive quality of life plan for Eastern North Philadelphia – the cops suggested that the neighborhood work to reclaim the park, dealing a blow to crime and giving local kids a safer place to play.

LISC anteed up $5,000 to get the project started, and APM is now attempting to put together a funding mix – some private, some city – to see the job through. The $150,000 plan calls for new fencing, lighting, play equipment and, just as important, a calendar of public events at the park to drive the drug dealers out.

“Within the next six months I think we’ll have something to show for our efforts,” Rodriguez said.

A video about the rec center at 8th and Diamond Streets. Story continues below….

Collaboration over confrontation

The handball court project is a modest one, but it’s illustrative of how APM operates, and how a non-profit organization can bring service improvements to a neighborhood without huge public investment.

Historically, grassroots organizations in Philadelphia have opted for one of two methods in their campaigns to get City Hall to pay attention to their neighborhood’s needs.

“A favorite is the squeaky wheel approach, where the organization is constantly making the rounds in City Hall, and leaning on elected officials, and eventually the organization or the person running it becomes known as someone you have to deal with because they’re so vocal and persistent,” said John Kromer, a former head of the city’s Office of Housing and Community Development who has authored a pair of studies about Eastern North Philadelphia this year.

That is not APM’s style.

Tire swings hang from trees at a small park on 5th street near York and Dauphin.

“The alternative is to actually work collaboratively with the city, and try and establish an understanding that the organization is serious, that its requests to the city will be appropriate and realistic,” Kromer said.

Given these budget-scrimping times, appropriate and realistic requests must be modest indeed. But there are still opportunities to enhance city services in neighborhoods that need them, particularly for organizations savvy enough to take advantage of them.

Consider Green2015, the Nutter administration endorsed plan to create 500 acres of new green space in the city in the next four years, which was developed for the city by PennPraxis (which is affiliated with PlanPhilly). The plan concluded that over 200,000 Philadelphians do not live within walking distance of a park. It also highlighted a host of neighborhoods – including the APM area – that lack fair and equitable access to green space.

Though its goals are ambitious, Green2015 is perhaps most notable for its clear-eyed realism. It acknowledges the city is not going to buy parkland by the square mile. Instead, it advocates an approach where existing public lands – from schools to rec centers to unimproved vacant city parcels – are made greener and accessible to the public, coupled with some limited acquisition of new land.

The Green2015 approach notes repeatedly that this sort of plan demands that the city work closely with community groups and CDCs. That suggests that neighborhoods with strong non-profits – like APM – will be particularly well positioned to get more green space.

“We’re going to move where there are opportunities to move. And we want to move in Eastern North Philadelphia because that’s an area that deserves it and is an area that currently doesn’t have equitable access,” DiBerardinis said. “I’ll be very interested in what APM is interested in. That would influence us, or at least give us some direction.”

DiBerardinis repeatedly said he did not have money to throw around.

“Green2015 is really about identifying existing resources and opportunities. I can’t go in there by myself and do it, I don’t have tens of million of dollars,” he said.

APM, though, has built its reputation as one of the city’s premier neighborhood non-profits by leveraging limited public investments into far larger projects, some of which have helped to lessen the impact of Eastern North Philadelphia’s distance from city service centers.

Cousin’s, the neighborhood grocery store, was lured to the area by APM following a long courtship, giving residents access to quality food at reasonable prices. The store now attracts residents from distant neighborhoods where fresher food is harder to come by.

APM is also now putting the finishing touches on a pocket park in the Cousin’s shopping center at the intersection of Berks and Germantown Avenues. The tiny park, featuring a small outdoor stage, was built without any direct city funding.

And next year, APM is slated to break ground on an ambitious, mixed-use development adjacent to the Temple Regional Rail station that is slated to include a computer lab and community meeting spaces, just the sort of services the city provides in other neighborhoods through libraries and rec centers.

Samiyah Beckham plays a board game at one of Eastern North Philadelphia’s few playgrounds located on 8th and Diamond streets.

Other organizations have helped fill in the gaps as well. The R.W. Brown Community Center at 8th and Cecil B. Moore is a facility to rival any public rec center. The center, run by the Caring People Alliance (an affiliate of the Boys & Girls Club of American) is not open to the general public, but many of the low-income children it serves are local residents.

And, of course, there is Temple University, Eastern North Philadelphia’s very-near neighbor. For proactive residents, the university offers a wealth of potential amenities, from use of computer facilities and library databases to low-or-no-cost meeting rooms, or even just as a safe place for kids to run around, protected by the university’s police force which patrols the campus and the blocks immediately surrounding it.

Historically, residents of the APM area have rarely ventured onto the university grounds, in part because the campus and neighborhood are divided by an imposing railroad viaduct, which makes Temple feel much farther away than it actually is.

But that too could change, once the construction of the TOD on 9th Street between Berks and Norris is completed.

“Our hope is that will open up the world for our neighborhood a little bit,” said Rose Gray APM’s community development chief. “We want it to link us to the campus and to the city as whole.”

Contact the reporter at pkerkstra@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.