Some pithy parting words from Jimmy Breslin

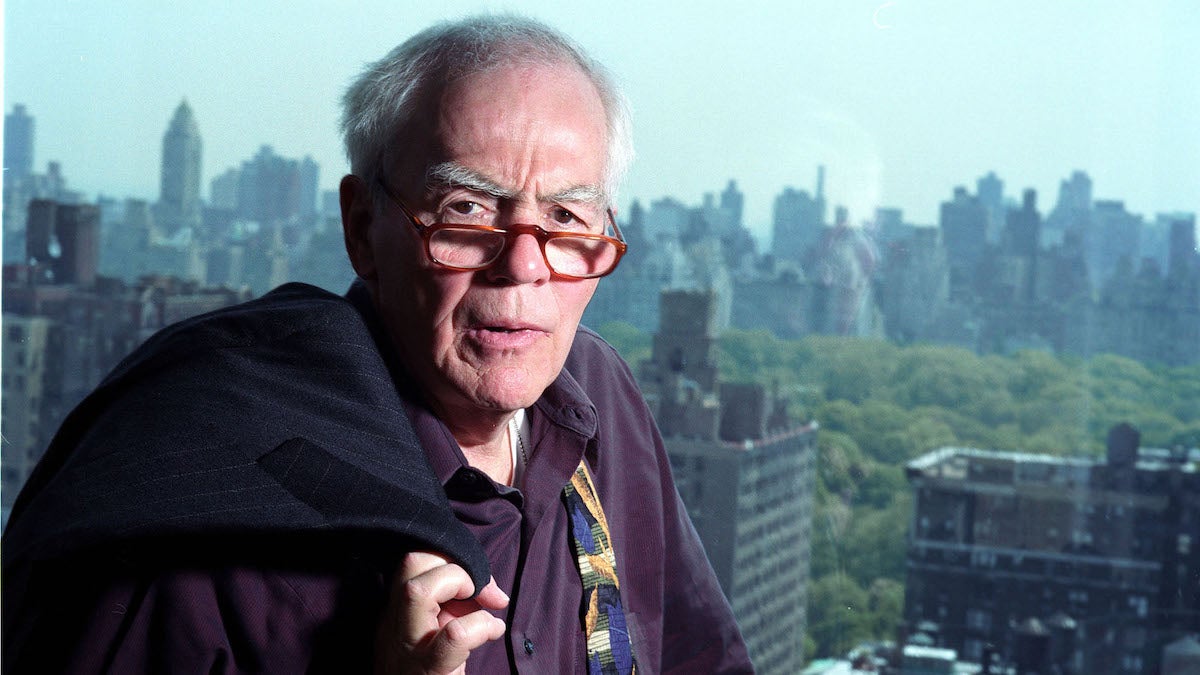

Columnist Jimmy Breslin poses in his New York apartment May 7, 2002. The Pulitzer Prize winner filed his last regular column, published in Newsday, on Tuesday, Nov. 2, 2004, (AP Photo/Jim Cooper)

Forgive me if I refrain today from writing about our craven King Leer. My reason is purely personal. It concerns Jimmy Breslin.

You probably knew him by name and reputation without ever reading a word he wrote. That’s understandable; a newspaper columnist’s work, cranked on deadline, is typically perishable. But Breslin, who died Saturday at age 88, was one of the rare birds who flew above the crowd. I read his blunt opinionated prose when I was a teen. He influenced me more than anyone else in the biz.

He was the prince of the pithy putdown. He called Rudy Giuliani “a small man in search of a balcony.” When nutjob serial killer David Berkowitz was captured, “the inside of his car looked like the inside of his head.” And Breslin indulged his rage in the fewest possible words. After three civil rights workers were killed by white racists in Mississippi in 1964, he wrote: “The funeral for Andrew Goodman was a lot of work. To begin, they had to kill him.”

Some Breslinisms have passed into the language. When pundits talk about the ephemerality of power, or a politician’s rhetorical trickery, they often use the phrase “blue smoke and mirrors.” That’s a variation of what Breslin coined in a ’70s book about Richard Nixon’s impeachment, when he wrote that “power is an illusion. Mirrors and blue smoke, beautiful blue smoke rolling over the surface of highly polished mirrors. If somebody tells you how to look, there can be seen in the smoke great, magnificent shapes, castle and kingdoms” – and, as Breslin pointed out, the illusion’s creator comes to believe it, too.

Best of all, Breslin’s instinct was to go it alone. He’d often ignore the hot news story and find a human narrative that was better than news.

I had Breslin in mind when I was 23, covering cops in a small city. One morning I heard on the police radio that some kids had found a grenade in their poor neighborhood. I got there pronto and began taking notes on everything, as I knew Breslin would. It later turned out that the grenade was a dud – no news! – so instead I wrote a narrative about bored kids eager for excitement. I delayed the dud revelation until the end of the story. My opening was pure Breslin mimicry: “Alberto Gonzalez is only 12 years old, but he can recognize a grenade. He said he sees them on television all the time. Alberto decided it would make a good plaything. It was overcast and cold, so the boys brought it to their home…Kids on bikes, kids yelling from their porches – it was the talk of the afternoon.”

By then, I’d already ingested the famous Breslin column written on deadline after JFK’s assassination. Granted, it’s “famous” only to those who’ve read it. While the press was focused on covering the luminaries in the funeral march, Breslin went off and found the guy who dug Kennedy’s grave. He wrote the global tragedy through the prism of the working stiff – a classic case of zigging when everyone else was zagging. Or, as he once put it, “I ain’t gonna get nowhere if I’m with everybody else.”

Let’s give Breslin the last word today. His grave-digger column ran on Nov. 25, 1963:

Clifton Pollard was pretty sure he was going to be working on Sunday, so when he woke up at 9 a.m., in his three-room apartment on Corcoran Street, he put on khaki overalls before going into the kitchen for breakfast. His wife, Hettie, made bacon and eggs for him. Pollard was in the middle of eating them when he received the phone call he had been expecting. It was from Mazo Kawalchik, who is the foreman of the gravediggers at Arlington National Cemetery, which is where Pollard works for a living. “Polly, could you please be here by eleven o’clock this morning?” Kawalchik asked. “I guess you know what it’s for.” Pollard did.

He hung up the phone, finished breakfast, and left his apartment so he could spend Sunday digging a grave for John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

When Pollard got to the row of yellow wooden garages where the cemetery equipment is stored, Kawalchik and John Metzler, the cemetery superintendent, were waiting for him. “Sorry to pull you out like this on a Sunday,” Metzler said.

“Oh, don’t say that,” Pollard said. “Why, it’s an honor for me to be here.”

Pollard got behind the wheel of a machine called a reverse hoe. Gravedigging is not done with men and shovels at Arlington. The reverse hoe is a green machine with a yellow bucket that scoops the earth toward the operator, not away from it as a crane does.

At the bottom of the hill in front of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Pollard started the digging.

Leaves covered the grass. When the yellow teeth of the reverse hoe first bit into the ground, the leaves made a threshing sound which could be heard above the motor of the machine. When the bucket came up with its first scoop of dirt, Metzler, the cemetery superintendent, walked over and looked at it.

“That’s nice soil,” Metzler said. “I’d like to save a little of it,” Pollard said. “The machine made some tracks in the grass over here and I’d like to sort of fill them in and get some good grass growing there, I’d like to have everything, you know, nice.”

James Winners, another gravedigger, nodded. He said he would fill a couple of carts with this extra-good soil and take it back to the garage and grow good turf on it. “He was a good man,” Pollard said. “Yes, he was,” Metzler said. “Now they’re going to come and put him right here in this grave I’m making up,” Pollard said. “You know, it’s an honor just for me to do this.”

Pollard is 42. He is a slim man with a mustache who was born in Pittsburgh and served as a private in the 352nd Engineers battalion in Burma in World War II. He is an equipment operator, grade 10, which means he gets $3.01 an hour. One of the last to serve John Fitzgerald Kennedy, who was the thirty-fifth President of this country, was a working man who earns $3.01 an hour and said it was an honor to dig the grave.

Yesterday morning, at 11:15, Jacqueline Kennedy started toward the grave.

She came out from under the north portico of the White House and slowly followed the body of her husband, which was in a flag-covered coffin that was strapped with two black leather belts to a black caisson that had polished brass axles. She walked straight and her head was high. She walked down the bluestone and blacktop driveway and through shadows thrown by the branches of seven leafless oak trees. She walked slowly past the sailors who held up flags of the states of this country. She walked past silent people who strained to see her and then, seeing her, dropped their heads and put their hands over their eyes. She walked out the northwest gate and into the middle of Pennsylvania Avenue. She walked with tight steps and her head was high and she followed the body of her murdered husband through the streets of Washington.

Everybody watched her while she walked. She is the mother of two fatherless children and she was walking into the history of this country because she was showing everybody who felt old and helpless and without hope that she had this terrible strength that everybody needed so badly.

Even though they had killed her husband and his blood ran onto her lap while he died, she could walk through the streets and to his grave and help us all while she walked.

There was mass, and then the procession to Arlington. When she came up to the grave at the cemetery, the casket already was in place. It was set between brass railings and it was ready to be lowered into the ground.

This must be the worst time of all, when a woman sees the coffin with her husband inside and it is in place to be buried under the earth. Now she knows that it is forever. Now there is nothing. There is no casket to kiss or hold with your hands. Nothing material to cling to. But she walked up to the burial area and stood in front of a row of six green-covered chairs and she started to sit down, but then she got up quickly and stood straight because she was not going to sit down until the man directing the funeral told her what seat he wanted her to take.

The ceremonies began, with jet planes roaring overhead and leaves falling from the sky. On this hill behind the coffin, people prayed aloud. They were cameramen and writers and soldiers and Secret Service men and they were saying prayers out loud and choking.

In front of the grave, Lyndon Johnson kept his head turned to his right. He is president and he had to remain composed. It was better that he did not look at the casket and grave of John Fitzgerald Kennedy too often. Then it was over and black limousines rushed under the cemetery trees and out onto the boulevard toward the White House.

“What time is it?” a man standing on the hill was asked. He looked at his watch. “Twenty minutes past three,” he said.

Clifton Pollard wasn’t at the funeral. He was over behind the hill, digging graves for $3.01 an hour in another section of the cemetery. He didn’t know who the graves were for. He was just digging them and then covering them with boards.

“They’ll be used,” he said. “We just don’t know when. I tried to go over to see the grave,” he said. “But it was so crowded a soldier told me I couldn’t get through. So I just stayed here and worked, sir. But I’ll get over there later a little bit. Just sort of look around and see how it is, you know. Like I told you, it’s an honor.”

————

By the way, Breslin had Trump’s number back in 1988:

“Trump, in the crinkling of an eye, senses better than anyone the insecurity of people, that nobody knows whether anything is good or bad until they are told, and he is quite willing to tell them immediately. His instinct appears to tell him that people crumble quickly at the first show of bravado…while he essentially runs crap games, the public associates him only with the highest buildings, the most fantastic dealings, personal presidential abilities…The man is the best boaster of his time.”

——-

Follow me on Twitter, @dickpolman1, and on Facebook.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.