See inside New Jersey’s hidden Hindenburg museum

-

Kevin Mulligan, a volunteer with the Navy Lakehurst Historical Society, tells tour-goers about a reproduction of the control gondola of the Hindenburg, which was created for a 1975 movie about the disaster. The historically accurate prop is housed in Hangar 1, and covered in a tarp to avoid potential damage from leaks. (Bill Barlow for WHYY)

-

Inside Hangar 1 where the Hindenburg was housed when it was in New Jersey in the 1930's. (Bill Barlow for WHYY)

-

One of the largest remaining pieces of the Hindenburg, a section of the interior alloy girders that held the airship together. (Bill Barlow for WHYY)

-

Kitchenware recovered from the Hindenburg crash site. (Bill Barlow for WHYY)

-

A drawing shows the interior layout of one floor of the airship Hindenburg. (Bill Barlow for WHYY)

-

A memorial to the Hindenburg is located on the spot where the airship crashed. (Bill Barlow for WHYY)

-

A smaller model of the Hidenburg at the museum in Lakehurst, N.J. (Bill Barlow for WHYY)

-

(Bill Barlow for WHYY)

-

A plaque marks the spot where the airship Hindenburg crashed. (AP File Photo/Mel Evans)

-

How the Hindenburg memorial looks from space. (Image via Google Maps)

-

(Bill Barlow for WHYY)

-

The Hindenburg memorial site is located on Lakehurst section of the military's Joint Base. (Bill Barlow for WHYY)

-

-

The German airship Hindenburg flies over the Olympic Stadium, outside Berlin, on August 1, 1936, during the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games. (AP Photo)

-

Spectators and ground crew surround the gondola of the German zeppelin Hindenburg as the lighter-than-air ship prepared to depart the U.S. Naval Station at Lakehurst, NJ, May 11, 1935, on its return trip to Germany. (AP Photo)

-

German airship 'Hindenburg' photographed from a plane, is seen flying over Manhattan Island, New York, USA in the 1930s. (AP Photo)

-

The German-built zeppelin Hindenburg is shown from behind, with the Swastika symbol on its tail wing, as the dirigible is partially enclosed by its hangar at the U.S. Navy Air Station in Lakehurst, N.J., May 9, 1936. (AP Photo)

-

The Hindenburg is shown just before it burst into flames in Lakehurst, N.J., on May 6, 1937. (AP Photo)

-

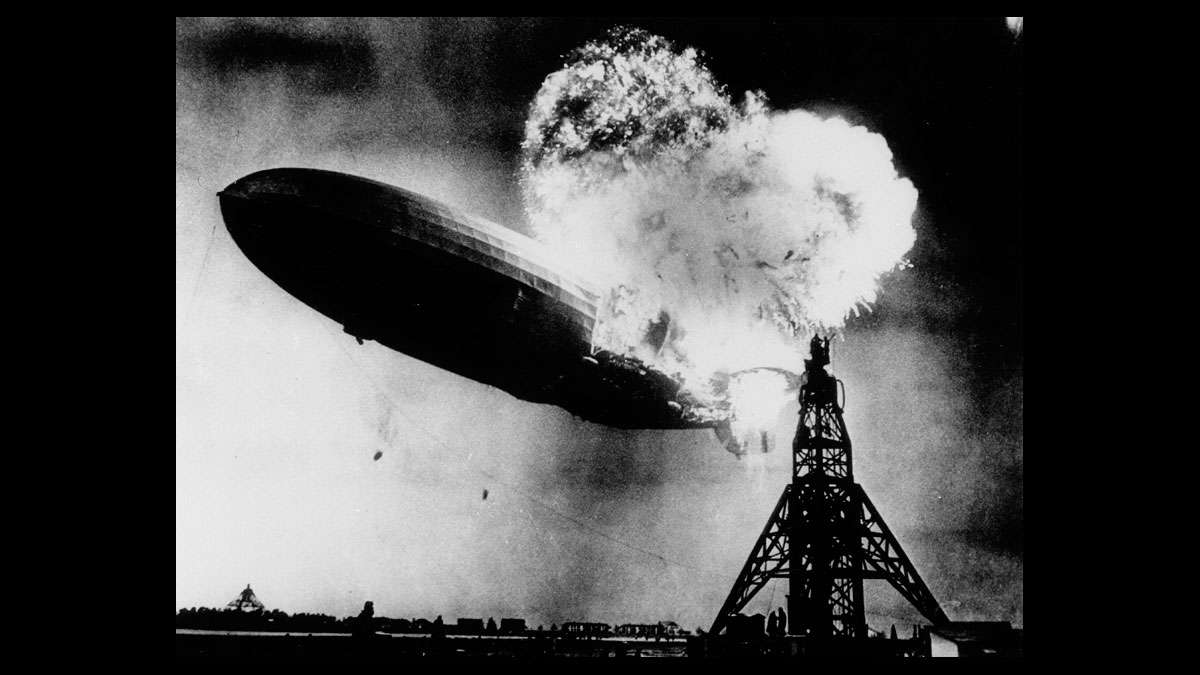

File - This May 6, 1937 file photo, taken at almost the split second that the Hindenburg exploded, shows the 804-foot German zeppelin just before the second and third explosions send the ship crashing to the earth over the Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, N.J. (AP Photo)

-

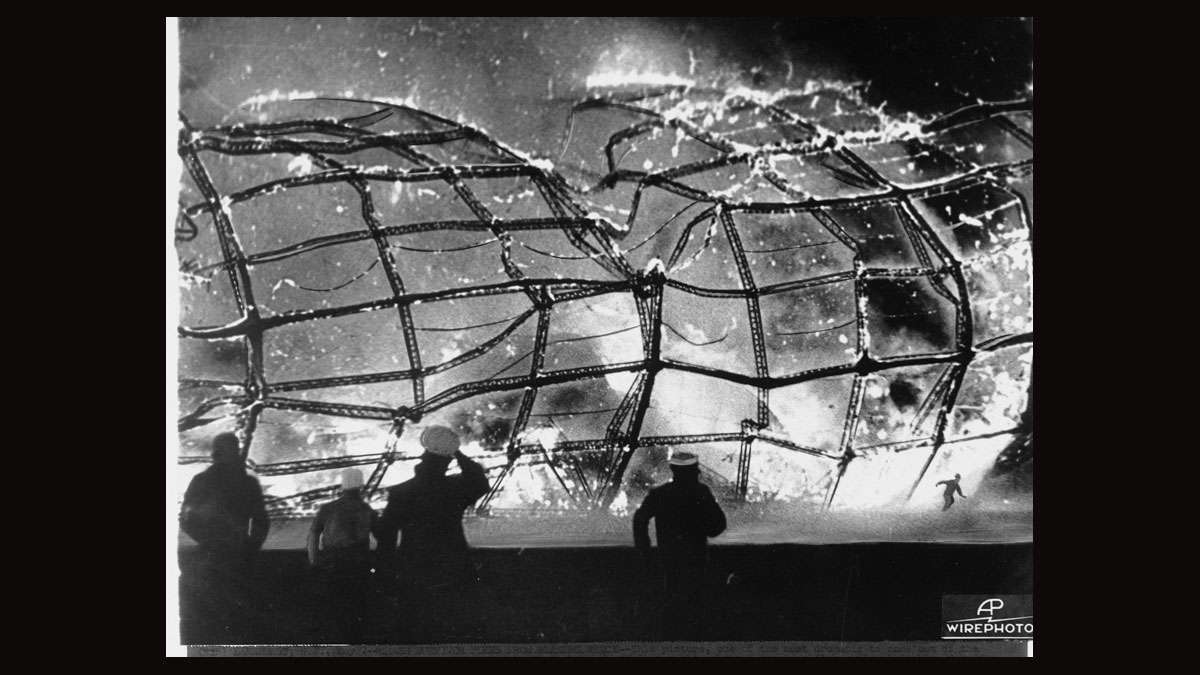

The burning Hindenburg is reduced to ruins as a survivor, lower right hand corner, runs to safety, May 6, 1937, after it exploded on mooring at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey. (AP Photo)

-

The Hindenburg zeppelin burns after it exploded during the docking procedure at Lakehurst Naval Air Station, N.J., on May 6, 1937. (AP Photo)

-

This is an aerial photo of the wreckage of the German Hindenburg airship at Lakehurst, N.J. on May 7, 1937. The airship exploded prior to landing on May 6. (AP Photo/Murray Becker)

-

The remains of the wreckage of the German Zeppelin Hindenburg are removed from the U.S. Naval field in Lakehurst, N.J., on May 15, 1937. The airship exploded mid-air prior to landing May 6. (AP Photo/Murray Becker)

-

Adolf Fisher, a mechanic of the German airship Hindenburg, is transferred from Paul Kimball Hospital in Lakewood, N.J., to an ambulance going to another area hospital, May 7, 1937. (AP Photo)

It sounds like fantasy; an enormous, luxurious airship, filled with one of the most world’s flammable gases, shuttling the super-rich around a globe still mired in the Great Depression.

For a summer, everything went fine. Made in Germany, the LZ 129 Hindenburg took 10 trips across the ocean in 1936 to land safely at the Lakehurst airfield, plus several more trips to South America. But on a spring evening 80 years ago, 7:25 p.m. May 6, 1937, that came to an end with one of the most visually spectacular air disasters in history.

It took just over 30 seconds for the airship to go from the zenith of floating luxury and privilege to a smoldering tangle of girders on the ground. The first landing of the season for the great zeppelin was national news, and photographers, radio announcers and film crews were on hand to capture the moment. Instead, they witnessed towering flames as the Hindenburg — more than 800 feet long and named for the German president who named Adolf Hitler chancellor — dissolved in gouts of fire and smoke.

Newsreel crews caught the disaster on film, something that seems familiar in the 21st century but was extraordinary at the time, and Chicago radio announcer Herbert Morrison made history with his commentary on the event, including the oft cited cry of “Oh, the humanity.” His brief statement was recorded and broadcast the next day.

Astonishingly, some survived. Of the 97 people on board, including 36 passengers and 61 crewmen, 35 were killed, including 13 of the passengers. A worker on the ground was also killed. Most of the others were injured or burned. While the hydrogen burned off in close to an instant, the diesel fuel for the four engines continued to burn through the night.

“This is where it all happened,” said Carl Jablonski, president of the Navy Lakehurst Historical Society, gesturing to a monument surrounded by a chain outline marking where the gondola of the Hindenburg landed 80 years ago. Two aluminum bleachers overlook the ground-level monument, but otherwise the site looks much like any other stretch of open field in New Jersey. The crash site is on the McQuire-Dix-Lakehurst joint base, which Air Force Staff Sgt. Dustin Roberts, a public affairs officer, says is the only base in the nation that includes Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine personnel. That means a visit includes passing a military checkpoint.

Now 75, Jablonski has been fascinated by lighter-than-air aviation for most of his life, since a visit with his father around 1947, when there were still Navy blimps at the site. His interest continued throughout his life, and he has served as president of the historical society for 22 years.

“It’s a labor of love,” he said.

He’s enthused about plans for marking the 80th anniversary, which includes a dinner on Friday evening at the nearby Clarion Hotel that was set to include comments from two of the three people alive known to have ever flown on the Hindenburg. Horst Schirmer was 5 when his father worked on the Hindenburg project and was allowed on board for some test flights, and Anne Springs Close was 10 when she was a passenger in 1936. In fact, she was the 1,000th passenger, for which she received a commemorative platter she was set to bring to the event.

He’s enthused about plans for marking the 80th anniversary, which includes a dinner on Friday evening at the nearby Clarion Hotel that was set to include comments from two of the three people alive known to have ever flown on the Hindenburg. Horst Schirmer was 5 when his father worked on the Hindenburg project and was allowed on board for some test flights, and Anne Springs Close was 10 when she was a passenger in 1936. In fact, she was the 1,000th passenger, for which she received a commemorative platter she was set to bring to the event.

On Saturday, May 6, a memorial service is planned at the site beginning at 6:45 p.m. The gates of the base will open at 5:30 for anyone who wants to attend, and the event will include remarks from Jablonski and Col. Frederick D. Thaden, the base commander. Typically, entry to the base requires identification, but Roberts said that will be waived for this event.

Interest remains

The Historical Society runs regular tours of the crash site and museums on base every Wednesday and the second and fourth Saturday from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. April through October, and every Wednesday and the second Saturday of each month November through March. Those who want to attend must register two weeks before the tour by calling 732-818-7520 or emailing navlake@prodigy.net.

According to the Historical Society, due to military security regulations, the tours are only open to United States citizens. Visitors are met outside the gates and escorted to the site. On Wednesday, May 3, a sizable crowd attended, ushered by longtime volunteer Nicholas Rakoncza while Jablonski spoke to a reporter.

Thoroughly versed in the history of the Hindenburg and the air station, Jablonski offers a flood of facts: the airship was 15 stories tall, and fully loaded, weighed 252 tons. In addition to passengers, it hauled mail and cargo for extra revenue, including an elephant on one journey. Its four engines allowed it to cruise at about 75 miles an hour, although it was capable of faster speeds, and typically flew at about 1,000 feet in the air, allowing for a smooth ride and spectacular views of the landscape below.

Commercial air travel was in its infancy at that point, and crossing on the Hindenburg was faster than the ocean liners that were the primary alternative. Heading west, the headwinds meant crossing the Atlantic in five or six days, but the same winds meant crossing from New Jersey to Europe took half the time. Passengers had bunks, but luxurious dining. A typical dinner menu included Rhine salmon and an extensive German wine list, one Jablonski described as exquisite. There was even a pressurized smoking lounge, although pipes and cigars had to be lit by the maître d, and passengers were obliged to hand over their matches before boarding. A one-way ticket was $450, about $740 for round trip, at a time when 50 cents an hour was a decent wage in the Northeast.

On its final flight, the first of the season to the United States, the Hindenburg faced a tough crossing, battling storms, hail and headwinds the whole way. Joblonski said the zeppelin passed through thunderstorms and St. Elmo’s Fire, a rare atmospheric glow that had been reported on sailing masts since ancient times.

The flight was more than 12 hours late, and while the passenger list was light on the trip west, the Hindenburg was fully booked for the return flight, with many of the high society passengers set to attend the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in London on May 12.

Joblonski dismisses a persistent sabotage theory. He and the other members of the Historical Society said there’s no reason to believe anyone deliberately caused the disaster, considering the volatile nature of the hydrogen gas that filled the airship. Running late, and with a limited time for a landing, the captain didn’t want to miss his landing time.

Jablonski said there was a strong wind at the field, easy to conceive when witnessing the wind at the site at the same time of year 80 years later, and the captain made two sharp turns in attempting to correct the orientation of the ship, sharper turns than were recommended. That may have led to a rupture of the internal structure, leading to a hydrogen leak. A tiny spark from static electricity could have started the rapidly spreading fire, the theory Jablonski and many experts see as the most likely cause.

If the ship had been filled with helium as originally intended, such a leak may have grounded the Hindenburg for repair, but it would not likely have injured anyone. But helium is extremely difficult to manufacture, and then as now, most of it is in the hands of the United States government. A federal law in 1925 prevented the sale of helium overseas, and there was little chance the government would make an exception for Nazi Germany.

“America would not sell helium to the German government,” Jablonski said. While the Hindenburg was a civilian ship, most dirigibles and blimps at the time were military, and Germany had used blimps in World War I. That meant a change in the design to use hydrogen, which could be extracted from air or water but was far, far more dangerous.

The tour also includes the Lakehurst Heritage Center, which includes some of the few existing remnants of the Hindenburg, including dinnerware and a section of the internal metal alloy girders that held the airship together. There are also several models of the Hindenburg, and information on the history of the base, including a period when ammunition was manufactured there for the Russian military before the 1917 revolution.

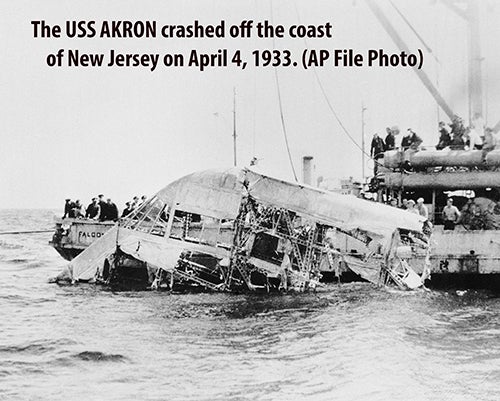

While by far the most iconic, the crash of the Hindenburg was not the first airship disaster. It was not even the deadliest; that unfortunate distinction falls to the USS Akron, an American ship filled with helium lost in a thunderstorm off the coast of New Jersey in April 1933, killing 73 of the 76 crew members on board. What’s worse, according to Jablonski, the Navy blimp sent to the scene to help with rescue efforts also crashed, killing two. Among the dead were Rear Admiral William A. Moffet, known as the father of American naval aviation and, according to Jablonski, a proponent of dirigibles.

The Akron was smaller than the Hindenburg, but only slightly. At the time of the crash, it was outfitted with small fighter planes, set for use as a flying aircraft carrier. Two years later, its sister ship the USS Macon crashed in California, but in part due to the lessons of the Akron, the crew were issued life preservers, and while two were killed, 81 crew members survived. Both the Macon and the Akron had moored at Lakehurst, and an earlier airship, the USS Shenandoah, was built in Lakehurst’s massive Hangar 1. That 680-foot airship crashed in 1925, another in a long history of destroyed airships.

On this day, Historical Society volunteer Kevin Mulligan is taking a group of soldiers on a tour of Hangar 1. At the start, he tells them the hangar is a little like the Grand Canyon. No matter how many times he’s seen it, it never loses the ‘wow’ factor.

Mulligan shows the group — part of an Army helicopter team on temporary assignment to the base – through the cavernous hangar. At one point, he said, the doors were opened on both ends and a biplane barnstormed through, but the hangar was built for airships like the Shenandoah. The Hindenburg was inside a couple of times. In fact, the ship’s original design was altered, reducing the length so that it could be contained in the hangar.

When the hangar was built, many believed airships were the future of flight.

But the very public destruction of the Hindenburg all but ended the age of the zeppelins. Some blimps were used during World War II as spotter craft, and during the Blitz, unmanned blimps were deployed over London as barriers to the Luftwaffe bombers, but it seemed clear that planes were the future of flight.

“We got out of the airship business in 1962,” Mulligan tells the visitors.

A turnaround may be possible.

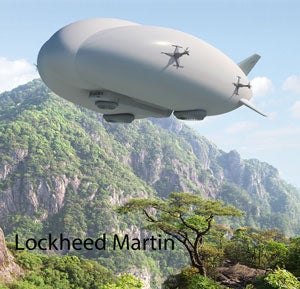

Lockhead-Martin is set to deliver a hybrid airship to Alaska for use as a cargo hauler in 2019, it’s been working on for 20 years. The airship had been presented for possible military use, but the airship is now billed as a way to bring large payloads and heavy equipment to remote areas inaccessible by roads. It’s even capable of landing in water or ice. And in December, Amazon received a patent for a giant floating warehouse blimp, from which drones could be launched to deliver goods. Before such a plan could take off, the company would face extensive obstacles, both in terms of engineering and getting FAA approvals.

Lockhead-Martin is set to deliver a hybrid airship to Alaska for use as a cargo hauler in 2019, it’s been working on for 20 years. The airship had been presented for possible military use, but the airship is now billed as a way to bring large payloads and heavy equipment to remote areas inaccessible by roads. It’s even capable of landing in water or ice. And in December, Amazon received a patent for a giant floating warehouse blimp, from which drones could be launched to deliver goods. Before such a plan could take off, the company would face extensive obstacles, both in terms of engineering and getting FAA approvals.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.