Remembering Martin Luther King’s gift of rhetoric

As I prepared to celebrate the Martin Luther King holiday, I listened to a sermon King delivered in a little Baptist church in Chicago in 1967.

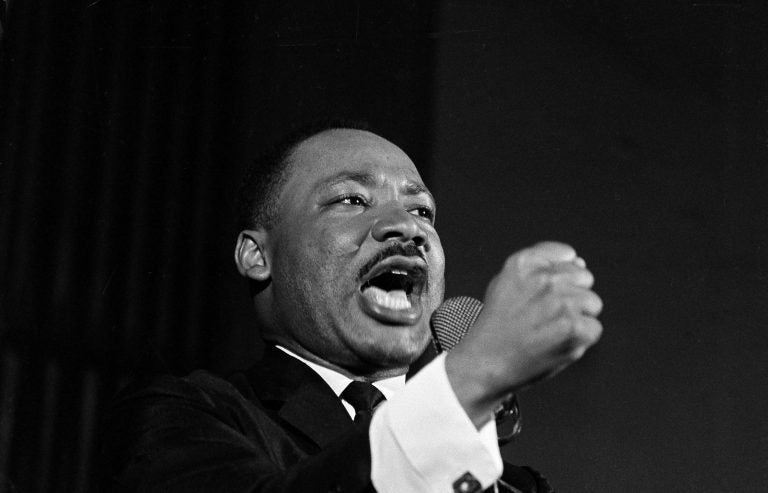

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. shakes his fist during a speech in Selma, Ala., Feb. 12, 1965. King was engaged in a battle with Sheriff Jim Clark over voting rights and voter registration in Selma. (AP Photo/Horace Cort)

As I prepared to celebrate the Martin Luther King holiday, I listened to a sermon King delivered in a little Baptist church in Chicago in 1967.

The sermon, taken from the Gospel of Luke, was based on the story of a foolish man who valued wealth over everything, including his immortal soul. But King in his genius understood that this was not just the story of a single man. It was the tale of America—a country that had lost its very soul to the twin ills of materialism and racism. The story of the foolish man was, in many ways, the story of all of us.

King was brilliant in his ability to boil America’s racial and class conflict down to soaring rhetoric that could both enthrall the intellectual and stir the common man. That rhetorical gift is on full display in much of King’s oratory, including his iconic “I Have A Dream” speech. But King was more than a man with a dream. He was a man of action, and for that, he was hated, threatened, abused, and reviled. But King was willing to pay the price to do what was right.

When he took direct action against discrimination in Birmingham, he was arrested on Good Friday, and sat in jail for 8 days. It was then that he wrote “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” his seminal essay on the need to protest against racism.

The letter was in response to white ministers who’d published an editorial claiming to support King’s cause, even as they decried King’s protests as “unwise and untimely.” King could not bear the hypocrisy of their position, and he said so in his famous text.

“You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham,” King wrote. “But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes. It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham, but it is even more unfortunate that the city’s white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative.”

It was this kind of frank truth telling, combined with King’s willingness to take to the streets, that made him a target during his lifetime.

When he marched against segregation in Chicago, King was attacked by an angry mob so violent that King said afterward, “I think the people of Mississippi ought to come to Chicago to learn how to hate.”

When he led the Montgomery bus boycott, and black people walked for over a year rather than sit on the back of the bus, King said he got up to 400 calls a day from racists who told him to stop the boycott or lose his life.

He spoke about one of those calls in the 1967 sermon he delivered in that little Baptist church in Chicago.

According to King, the call came in about midnight, and an ugly voice on the other end of the line said, “Nigger, we’re tired of you and your mess now, and if you aren’t out of this town in three days we’re going to blow your brains out and blow up your house.”

King was afraid, he said, and it was then that he had to learn to lean on his faith.

In order to do so, King had to be willing to pay the price to do what was right.

That price was far more than threats and violence from racists. It was also criticism from black people who were unwilling to support King’s confrontational tactics.

He was hated for speaking out against the Vietnam War at a time when Americans were expected to give unconditional support to our nation’s military. He was hated for speaking out against poverty and for trying to address the commonalities between poor blacks and whites. He was hated because he had come to understand that America’s divisions were driven by class as much as race.

So as we celebrate King today, please know that his service to our nation was bigger than a dream. It was more consequential that painting a building or filling up backpacks.

King’s service was about making America face the fact that its wealth was created by black people—the very people that our nation has continued to kill in the streets, force into ghettoes, and deny opportunity.

Have things gotten better since King’s time? Yes. But we’ve still got a fight on our hands. African Americans and our allies must fight so black workers have access to decent wages and black children have access to decent schools. We must fight so black families have access to decent housing and can live in safe communities.

All of these things are imminently achievable, but if we are to truly celebrate King’s legacy, we must be willing to do what King did—pay the price to do what’s right.

—

Listen to Solomon Jones weekdays from 10 to Noon on Praise 107.9 HD2

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.