Philadelphia auction treasure a reminder of racist Wilson presidency

An antique book found at a Northern Liberties vintage shop will fetch a nice price at auction, but as a bridge between the Confederate South and the Wilson presidency, it’s a reminder of segregationist acts that weakened America.

Michael Pace is a manager of Jinxed, one of Philadelphia’s growing number of “vintage goods boutiques.” To stay competitive, Pace keeps his inventory updated with miscellany that he purchases by the container at auction and estate sales.

“We don’t really want to find big-ticket items,” said Pace. “All that we’re looking to do is to move things as quickly as possible.”

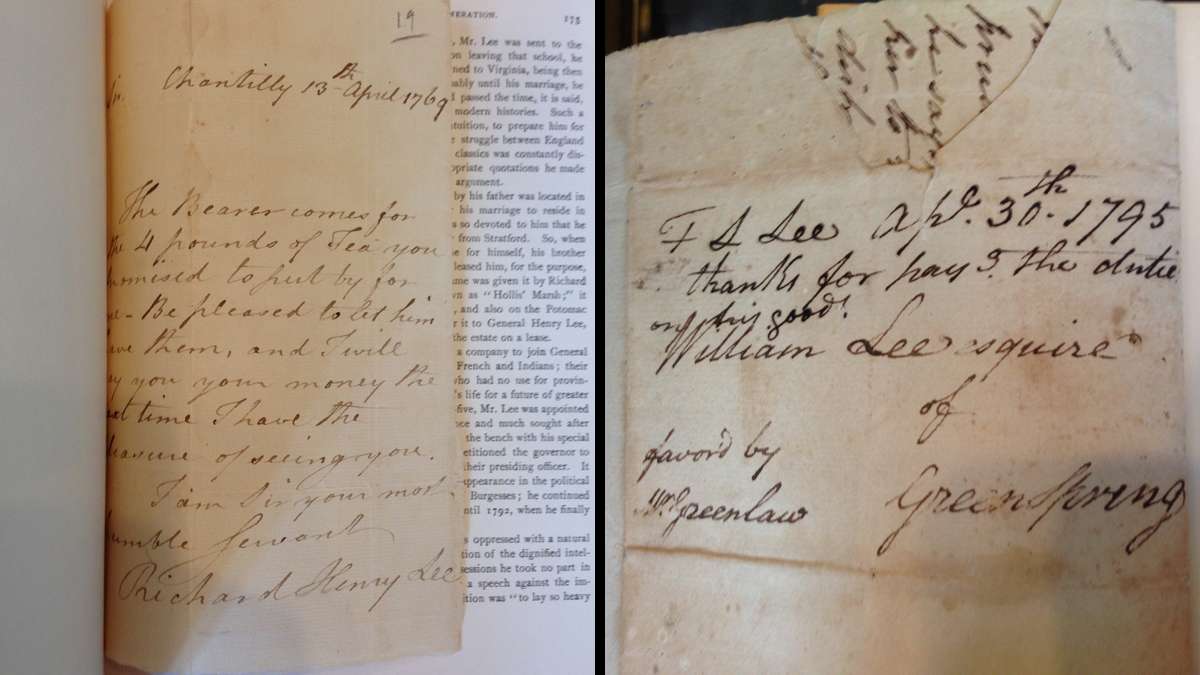

A few months ago, Pace discovered a “big-ticket item” at the store’s Northern Liberties location in the Piazza. At the bottom of a box topped with religious icons and housewares, he saw a book called Lees of Virginia, 1642 -1892. A loose binding caused the pages to fan from the covers, and Pace noticed that someone had glued handwritten letters, receipts and photographs within the pages. Pace didn’t recognize the name of the author, Edmund Jennings Lee, or that of his daughter, Constance Gardner, to whom Lee had inscribed this book. He did recognize a name signed to a postcard inside of the front cover: that of Woodrow Wilson, the 28th president of the United States.

The postmark indicated that Wilson or an assistant had mailed the card from Princeton, N.J., on August 28, 1895, six days before the book’s publication.

My dear Sir, Not knowing how otherwise to reach you, I venture to address you in the care of the Pa Historical Soc’y, to ascertain of whom I can obtain a copy of your recent book, “Lee of Virginia, 1642-1892″. The price, I believe, is ten dollars?” Very truly yours, Woodrow Wilson.

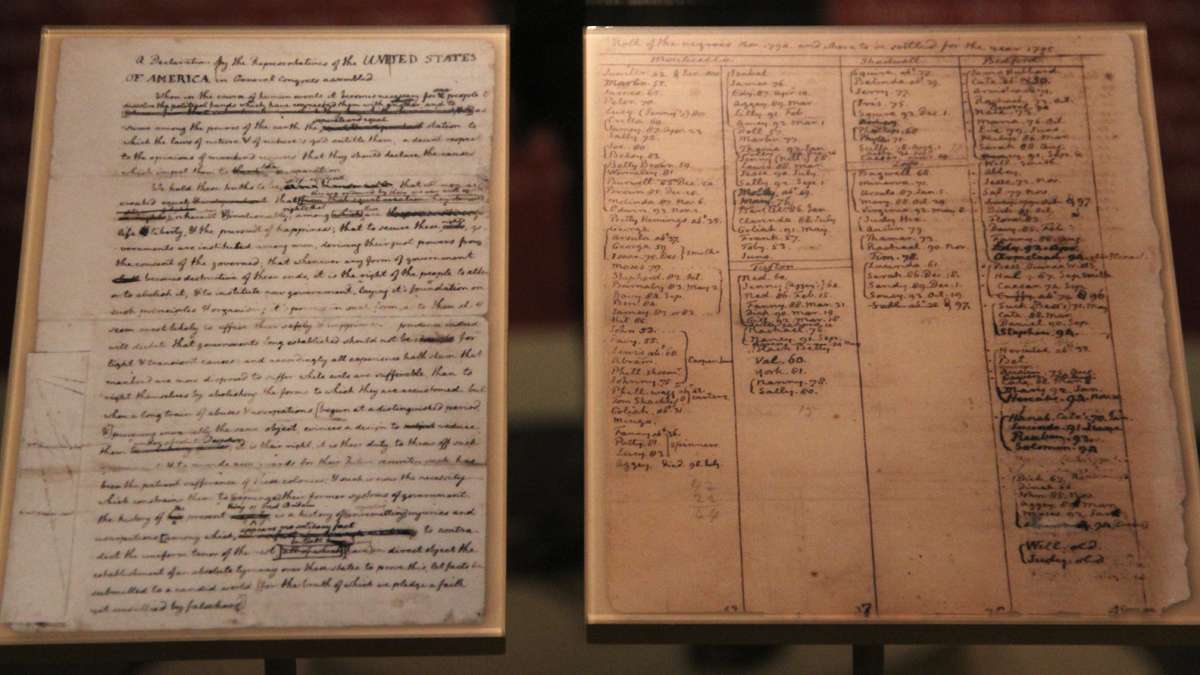

Edmund Jennings Lee, was the first cousin once removed of Robert E. Lee. In the book, he traces the genealogy of one of America’s most famous political and military families from their immigrant ancestor Richard Lee I, a tobacco merchant. Lee’s oldest daughter, Constance Gardner, turned her copy of the book into a family scrapbook: Near the biographical entries of her relatives, she glued photographs and papers that the family had preserved. Among her attachments are two letters written by brothers Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee, both signers of the Declaration of Independence.

The Jinxed find will go to auction in three separate lots at Freeman’s on April 10.

An admiration for the Confederate South

In 1895, Woodrow Wilson had taught law and political science at Princeton University (then The College of New Jersey) for five years. His interest in the Lee family is recorded in a speech that he gave at the University of North Carolina 14 years later (on January 19, 1909), when he was then president of Princeton University. The occasion commemorated Robert E. Lee on the anniversary of the Confederate general’s birthday. Like Lee, Woodrow Wilson grew up in Virginia, and he included in his talk a short anecdote about seeing the war hero in person; after Lee surrendered at the Appomattox Court House, a Union Guard marched him through Staunton, where Wilson as a 9-year-old child watched him pass by.

“I have only the delightful memory of standing, when a lad, for a moment by General Lee’s side and looking up into his face,” said Wilson.

The scope of Wilson’s speech concentrated on Lee’s legacy as a national hero in spite of his commitment to the land and ideology of his “local rootage.” He says his remembrance of Lee “takes me back to my own feeling about one’s necessary connection with the region in which he was born.”

A presidency of segregation

Later In 1909, Woodrow Wilson would leave his professorship for the New Jersey governor’s seat, where he would campaign for the presidency in 1912. Had more voters known about the speech that Wilson gave on Robert E. Lee in January of 1909, they might have anticipated his discriminatory policies. Instead, African American voters largely trusted Woodrow Wilson’s campaign promises.

“Should I become President of the United States,” the governor said in 1912, “[African Americans] should count upon me for absolute fair dealing and for everything by which I could assist in advancing the interests of their race in the United States.”

In August of that year, The Crisis encouraged its readers to vote against incumbent William Howard Taft, calling his conservative tenure a “surrender to Southern prejudice.” The magazine encouraged its readers to cast their votes to Wilson. Although black leaders knew that the Southern Democrat wouldn’t be their friend, they trusted that the “cultivated scholar” would “treat black men with fairness.”

But President Wilson adhered to his southern nostalgia when addressing race relations. Less than a year after taking office, he had segregated the government’s civil service, reversing the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883. Signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur, the legislation called for merit-based appointments and promotions based upon test scores, not political maneuvering. As a result of Wilson’s decision, bureaus demoted African-Americans in leadership positions and dramatically reorganized office culture. Under the guise of “readjustment … to create efficiency,” employees rearranged desk patterns and reassigned personal lockers to separate the races. By August of 1913, both the Departments of Treasury and the Post Office had re-segregated bathrooms and meeting areas. Black employees had to use separate lunchrooms and they were no longer welcome to “welfare work meetings” at the White House.

When Wilson took office, African-Americans were in 26 federal and diplomatic leadership positions. By 1918, his administration had reduced the number to seven. Publicly, the president stated that he believed segregation was “to [African Americans’] advantage” because it would limit racial “friction.”

A rotten ‘rootage’ comes to bloom

In its January 1914 issue, The Crisis excerpted editorials questioning the changes in Washington. A quotation from one unnamed paper linked Wilson’s present views to his boyhood. The writer said the key to President Wilson’s racial views “is that of early environment, and the traditions of his youth.”

Wilson’s segregationist acts may have strengthened the former president’s Virginia roots, but his decision to reverse merit-based positions created a culture of unchecked political appointments within the Civil Service Commission for 66 years. The Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 officially dismantled the commission in 1979, arguably because of the way President Nixon and his staff used it to help facilitate the Watergate scandal.

History exalts President Woodrow Wilson for his progressive, isolationist agenda, his international peacekeeping efforts and his tax and banking industry reforms. But the Jinxed find is a reminder of segregationist acts that weakened America. Wilson’s postcard and Constance Lee Gardner’s copy of the book will be sold together on April 10 and are valued at $200-$300. Freeman’s has estimated the letters of Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee at $2500-4,000 each.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.