Philadelphia and New Orleans — separated at birth?

William Penn never wandered down Bourbon Street, and it’s unlikely that Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville ever dipped his feet in the Delaware, yet the cities that these men founded, are strikingly similar. Though more than 1,100 miles apart and certainly not identical, it isn’t difficult to imagine Philadelphia and New Orleans as siblings, or at least cousins.

The French connection

Bienville, a French colonizer born in Quebec founded La Nouvelle Orleans in 1718 in the French territory of Louisiana. Making the overly optimistic assessment that the site, on higher ground than its surroundings, was safe from tidal surges and storms, he established the city at a bend in the Mississippi. Soon it became the territorial capital. Despite the city’s increasingly diverse population and its coming under Spanish control in 1763 and American control in 1803, the French never ceded control of the culture and language. Whatever country it belonged to, New Orleans was a French city.

As colonists in Philadelphia became dissatisfied with British rule, the French Enlightenment provided the philosophical argument for independence. When the break was finally made, France provided essential support for the revolution and the young nation. Centuries later, French influence is still evident in Philadelphia’s design, art, and culture. The Benjamin Franklin Parkway was modeled on Paris’ Champs-Elysées. Philadelphia City Hall exemplifies Second French Empire style. The Academy of Music was designed by Frenchman Napoleon Le Brun. Collections of Rodin and other 20th century French artists here are the most extensive outside of France. And each July 14, Philadelphians mark French independence, enthusiastically mocking Marie Antoinette with cries of “Let them eat Tastykake!”

The man who built the mints; the couple who saved jazz

Philadelphia architect William Strickland designed both Philadelphia’s second mint building (built 1833, demolished 1907) and the New Orleans Mint (1838). Though New Orleans ceased minting in 1909, it was the only southern mint to resume making money after the Civil War. It produced coins for not only Louisiana and the United States, but also for a few months in 1861, the Confederacy. Today the Old Mint holds riches of jazz history, including Preservation Hall at 50, a retrospective of the iconic French Quarter performance space.

Preservation Hall is yet another Philadelphia tie. Early in the 1960s, University of Pennsylvania grad Allan Jaffe and his wife Sandra went to New Orleans to hear traditional jazz. They were dismayed to find the music, and the musicians who created the art form, teetering on extinction. With others, the Jaffes formed the New Orleans Society for the Preservation of Traditional Jazz.

Though the society didn’t last, the commitment to preserve jazz and support its players did. The couple bought a St. Peter Street art gallery and began presenting traditional jazz nightly. More than a half-century later, their son Ben runs Preservation Hall, a tiny, unadorned room that attracts international audiences who wait in long lines for first-come, first-serve tickets.

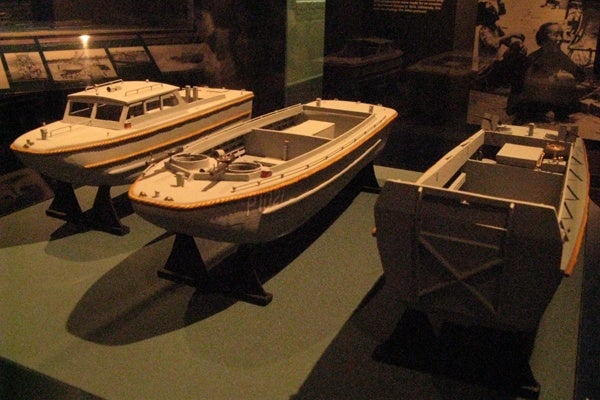

The boats that won the war

While Philadelphia has a more placid relationship with water than New Orleans, both cities have a history of boatbuilding, and that experience was critical during World War II. At the peak of the war, the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard employed 58,000 people and produced the battleships Washington and New Jersey, along with the aircraft carrier Antietam, destroyer escorts, and landing ships.

Landing craft were New Orleans’ significant contribution, built by a man who understood how to navigate Louisiana swamps without snagging roots, mud or other debris. Andrew Jackson Higgins knew immediately that his boats were ideal for ferrying troops and equipment from larger ships through shallow water to heavily fortified coasts. Known as LVCP (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel), the Higgins boats were used in the Pacific, in north Africa, and in France, most notably in the Normandy invasion on D-Day. The nimble wooden boats were so valuable that Dwight Eisenhower, who directed the D-Day assaults, credited Higgins with winning the war for the Allies. The achievement was a key reason for locating the National World War II Museum in Higgins’ hometown.

The woman who became a saint

The cities have a Catholic saint in common: Katharine Drexel, a Philadelphia girl who founded a religious order here and a university there. In 1891, St. Katherine used her family inheritance to form the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, and devoted her life to educating Native American and Black students. In New Orleans, she founded a school that in 1925 became Xavier University. Xavier remains the only university that is historically Black and Catholic, though today its 3,300 students represent varied ethnic and religious backgrounds.

The parade tradition

Then there is the cities’ shared tendency to dress in sparkly costumes and march through the streets. The only difference is that, while Philadelphia focuses its revelry on New Year’s Day, New Orleans and southern Louisiana celebrate for six weeks, from Jan. 6 through Mardi Gras. Louisiana’s parading dates from 1699. Philadelphia’s mummery began in the late 17th century, though the official parade dates from 1901.

In New Orleans alone, 60 parades roll out during the last two weeks of carnival season. On Mardi Gras, the climax of the season, visitors are warned that if their dinner reservations require them to cross a parade route, they probably will be late.

Superficial differences aside, compare Mardi Gras suits and floats with the Mummers, and you can almost hear the glockenspiels and saxophones at Broad and Tasker.

The sammies

Whether in New Orleans or Philadelphia, it’s good to bring an appetite. Both cities take pride in what they put between two pieces of bread. Philadelphia’s hoagie and cheesesteak are answered by New Orleans’ po-boy and muffaletta, a savory concoction of Italian meats and cheeses anointed with olive salad on a bun of Biblical loaves-and-fishes proportions.

An area in which Philadelphia can’t compare, however, is in cocktails. Whether creating, carrying, or consuming alcohol, New Orleans wins, hands down. It’s hard to say which would be more fun to observe: Mardi Gras revelers wandering the aisles of a Pennsylvania state liquor store, or members of the Liquor Control Board on a field trip to the French Quarter.

With that exception, seeing New Orleans through Philadelphia eyes is like glimpsing a friendly face in an unexpected place. You know it can’t be what you think, but it looks so familiar.

—

Pamela J. Forsythe, a writer and communications consultant in Philadelphia, recently traveled to New Orleans.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.