Saving the ‘sky puppies’: How one wildlife rehabilitator is working to rescue bats in Pa.

In the face of devastating population loss throughout the region, every bat that the Pennsylvania Bat Conservation and Rehabilitation is able to save is making a difference.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Alongside the 12-foot-tall skeletons, witches riding on broomsticks, black cats and hooded grim reapers, bats often grace porches and doorways this time of year.

But at the Pennsylvania Bat Conservation and Rehabilitation Center, these nocturnal animals associated with Halloween, vampires and the occult are affectionately known as “sky puppies.” On a warm day in October, the center’s current residents, including Betty White, Zeusy Pooh, Nutmeg and Chatterbox, snuggle into blankets and roost amid leaves, chirping as they munch on mealworms for a midday snack.

The center is the largest of its kind in the Northeast, and in the top five largest in the country, taking in more than 300 bats annually.

Stephanie Stronsick, president and founder of the center, has been working with bats for 18 years.

“Growing up, I was not really afraid of anything,” she said. “I spent a lot of time outside, so snakes, spiders, bats, nothing really scared me … It was fun and adventurous, and it kind of led into my life path.”

Stronsick started her career in wildlife rehabilitation in California, working with a number of species, but realized the center she worked at didn’t rehabilitate bats.

“I was like, ‘Why not bats?’ And come to find out, they’re very challenging. They’re not like any other animal to rehabilitate,” she said.

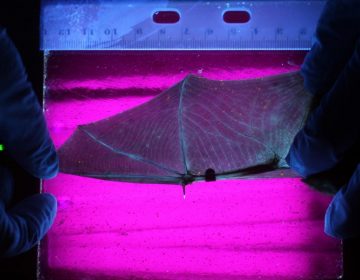

Bats are the only flighted mammal, and experience a vast amount of physiological change throughout the day and during the different seasons of the year. They also are easily stressed by the presence of other animals, which means they need specialized care and conditions in rehabilitation, Stronsick said.

The center serves 29 counties in the eastern and southeastern part of the commonwealth, Stronsick said. She works with a team of volunteers to respond to calls to the center’s hotline about grounded bats and facilitate their transportation from where they’re found to the center’s rehabilitation space in Mertztown, Berks County.

Of the bats the center took in last year, Stronsick said they were able to release more than 200 of them back into the wild.

Bats that cannot be released can become education animals and have a permanent home at the center, she said. Those that don’t survive are sent to universities for research purposes.

As Pennsylvania’s bat population has suffered devastating losses because of white-nose syndrome, rehabilitators are essential in safeguarding the species that play a vital role in the region’s ecosystems.

White-nose syndrome decimates Pennsylvania’s bat populations

White-nose syndrome has killed millions of North American cave bats. The fungus causing the disease was first found in Albany, New York, in 2006, but originally came from Europe or Asia, where bat populations are resistant to it.

The disease impacts hibernating bats that roost in caves, abandoned mines and other structures during the winter months. The fungus also thrives in colder temperatures and lives in the soil. Once its spores spread to the roosting bats, it starts to attack the bats’ membranes and disrupts their hibernation, causing them to wake up and deplete their fat stores needed for the winter.

“Pennsylvania was one of the hardest-hit states because we have a lot of hibernacula here,” Stronsick said.

The estimated population of the little brown bat, once the state’s most abundant bat, was between 3 and 5 million before white-nose syndrome was first identified in the state in the winter of 2008. Now, there’s about 5,000, with only 1% of the population remaining.

“We’re looking at a 99.9% decline of our bats,” said Greg Turner, state mammalogist for the Pennsylvania Game Commission.

The decline in bats has a myriad of environmental consequences, he said.

“All of our bats are insectivores, so they’re eating mosquitoes and midges and moths,” he said. “Some of these insects carry diseases. Some of them cause damage to our crops. And so bats play a key role in keeping a lot of these insects at bay.”

Advances in how to treat white-nose syndrome and better support bat populations in the face of the devastating disease has made Turner feel “cautiously hopeful,” he said. But he worries about continued population recovery for the long-lived species — bats can live for up to 35 years, and reproduce slowly, so it’s hard to know how many surviving bats are of reproductive age, and how younger bats are faring against white-nose syndrome. He also is concerned that any additional disease or infection introduced to local bat populations could further complicate population recovery.

That’s where the work of Stronsick and other rehabilitators in the region comes in, Turner said. Female bats have been more impacted by white-nose syndrome, since they hibernate longer, so there are now more male bats than female bats.

“Every female that can be saved by rehabbers … gives that species, that population, a leg up on persistence into the future,” he said. “The more females we have, the sooner we have them, and the more they’re able to produce young, the faster we can start seeing recovery. And for such a long-lived and slow reproducing species, we’re already looking at a very long timeline for some semblance of recovery.”

Turner and his team have also worked with Stronsick in research on the disease and helping infected bats recover.

In addition to white-nose syndrome, Stronsick said that bats also face a number of other threats, including human degradation of the environment causing fragmented habitats. Cityscapes impact migrating bats, who can collide with windows or are hit by cars. Wind turbines also pose a threat, killing a significant number of migratory bats each year.

For Stronsick, every call to the center’s hotline is also a sign of hope for bat species in Pennsylvania. She said the devastating impacts of white-nose syndrome have contributed to more awareness of bats’ importance.

“It’s heartwarming that more people are showing interest and compassion for this animal,” she said. “I started rehabbing before white-nose syndrome, and it was a different world back then. So unfortunately, it took us losing our keystone species, because entire ecosystems rely on them to be a part of it, and it took us losing them almost to extinction until we really understood their ecological significance.”

How to support bats in the Delaware Valley

Rescuers and researchers say there are a number of things people can do to support bats in the region.

If you see a grounded bat, Stronsick said, that means they’re in need of help.

“You taking that time out of your day to find professional help and not whack it with a broom or kill it, that is one more life that is saved,” she said. “Because we are losing our bat species in high abundance. A lot of our bat populations are even on the verge of extinction.”

If you spot a bat in need, she said, here is what you should do.

- Wear garden gloves or use a thick towel to handle the bat

- Put it in a safe container with a secure lid with no holes or gaps larger than a quarter inch

- Don’t offer food or water, and don’t leave it out in the sun

- Call a rescuer. Pennsylvania Bat Conservation and Rehabilitation Center has a hotline you can call: 484-908-0231. In Delaware, you can call the Delaware Bat Rehabilitation and Conservation Center at 302-342-9211

Stronsick’s work in Pennsylvania has also helped support the Delaware Bat Rehabilitation and Conservation Center, which was founded by Kesha Braunskill in 2023.

The Delaware center now takes in more than 100 bats a year and does outreach and programming to educate people about the importance of bats.

“I feel like bats are kind of like a gateway species to have that broader conversation about conservation,” said Braunskill, who has a background in wildlife, ecology and forestry. She also is a citizen of the Lenape Indian tribe of Delaware, and does youth programming with the Lenape and Nanticoke tribes in the region.

Braunskill said she works to challenge people’s misconceptions about bats, including people’s fears about getting rabies from bats.

Bats are a rabies vector species, and can contract it, pass it on and die from it like many other animals. But the overall percentage of bats infected by rabies is extremely small, Braunskill said, although everyone should always take proper precautions.

To help bats and the environment as a whole, Braunskill recommends:

- Planting native species

- Avoiding or using less pesticides and herbicides

- Decreasing light pollution

- Don’t use web decorations for Halloween that bats and other animals can get caught in

- Consider whether putting up a bat box with a pup catcher could work for you and your yard. Bat boxes can help fight against white nose syndrome

“We’re seeing habitat destruction, and all these things are also affecting bats, but also affecting our insect population and our other wildlife … There are all those interactions at play, and bats are a part of those interactions,” Braunskill said. “And when you start to remove one of those things, it’s affecting that web of interaction.”

Turner, from the Pennsylvania Game Commission, also encouraged residents to support federal funding for science that is helping bats and the environment as a whole.

Pennsylvania residents can also participate in the Appalachian Bat Count, if they have colonies nearby and are able to count the number of bats there two to three times a year.

For Stronsick, each action to help support bats and their environment makes a difference.

“Every individual does matter, and that’s what gives me hope,” she said. “People do care, and hopefully more people will continue to care, and we will start protecting their environment and protecting all landscapes that are required for these animals to thrive in.”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.