Penn and Philadelphia Art museums collaborate on ‘Creative Africa’

ListenThrough this summer, the Philadelphia Museum of Art is showing five different exhibitions related to Africa. “Creative Africa,” taking the entirety of the Museum’s Perelman Building annex, ranges from ancient tribal art to fresh contemporary design.

The Museum does not have a particularly strong collection of traditional African art, but it does have a strong partnership across the river with the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Archeology and Anthropology, which has a huge African collection.

The two institutions collaborated on “Look Again: Contemporary Perspectives on African Art,” the centerpiece of “Creative Africa.” The show emphasizes the physical artifacts on their own, more than their historical and cultural context.

For example, viewers are invited to inspect a collection of 19th century power figures from the Kongo people of Central Africa, wooden sculptures imbued with supernatural abilities to protect and avenge the owner. The wall text urges an appreciation of the physical qualities of the object and how it compares with similar figures.

“Before we frame them with didactic material and maps and which societies are matriarchal and patriarchal, we are asking you to use your eyes and common sense and see what the objects can tell you in their own right,” said independent curator Dr. Kristina Van Dyke.

Unlike the Penn Museum, whose Africa exhibition goes into detail about the meaning of symbols and the cultural-historic moment out of which they came, the Art Museum is more interpretive. Even the setting of the show — with gleaming white walls and crisply painted turquoise pedestals — puts the dark-wood and earth-toned objects in a bright, modern environment.

“In my view, as a great encyclopedic institution, we need to bring the past in to conversation with the present,” said the Art Museum’s CEO Timothy Rub.

Outside of “Look Again,” the Museum is able to show off its impressive holdings of African textiles, both traditional and modern. Each has its own, respective exhibition. In a small, 2nd floor gallery, traditional African woven cloth show intricate linear patterns, some shaped with undulating edges of palm fibers.

The most colorful room of the exhibition is the fashion and textile exhibition, showing bright, boldly patterned textiles printed with the beautiful and bizarre: fallen trees according to proverb (“One tree along cannot stand the wind”), an arrangement of chickens, a pattern of rear-view mirrors festoon the walls.

The fabric patterns area closely associated with Western and Central Africa, but they are actually designed and manufactured by a Dutch company, Vlisco, which began exporting textiles to the African market in the 19th century.

Because of the way the fabric is printed, just 36 inches wide with a horizontal pattern, African tailors and seamstresses have to use different techniques from their European counterparts. Different patterns and colors abut each other loudly, and clothes often need to be designed from scratch.

“It fosters a lot of creativity,” said Museum curator of costumes and textiles, Dilys Blum. “It’s much more of a collaborative process in design. It doesn’t follow the Western fashion tradition.”

The complications of trying to identify a purely African art in a globalized world is embodied in the architect Francis Kéré, who grew up in a small village in West African nation of Burkino Faso. He left to study architecture in Germany.

While still a student, in 2000, he designed a school for his village, Gando, with native materials, passive cooling, and innovative building techniques that could be adopted by the villagers. The textbook German modernism he was learning would not work in Burkino Faso.

“I came from a very poor village where there was no school. There it is hot. 100 degrees. Very hot,” said Kéré. “I used my skills and adapted it to the climate condition, and to the social condition of the people.”

Since then Kéré has executed several projects in Africa, each sensitive to the climate and economics of the environment: even if electricity is available it might not be reliable, so using modern mechanical systems in buildings is not be sustainable in some villages. He uses, for example, a canopy of hanging clay pots to create a temperature envelope that allows for air circulation.

Kéré is still based in Berlin, and uses his sensitivity to land and climate in design projects in Kenya, Italy, and Louisiana.

“Even if I do something somewhere else, I’m trying to figure out what can I use to achieve the biggest impact, in terms ofeconomy, for maximum ventilation, and material,” said Kéré.

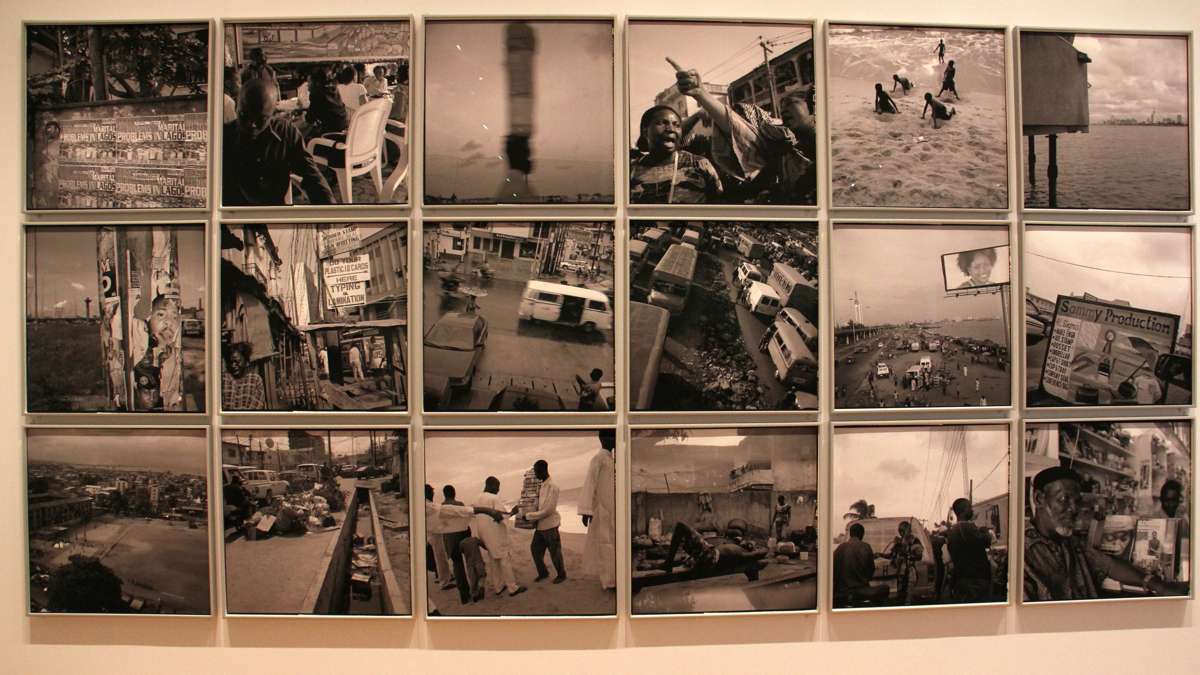

The exhibition also features contemporary photography in six African cities by three photographers, from Mali (Seydou Camara), Nigeria (Akinbode Akinbiyi), and Ivory Coast (Leki Dago). They range from urban documentary (overcrowding in Lagos, the underground bars of Soweto) to more formal images of people preserving ancient Islamic texts in Tombouctou.

The five parts of “Creative Africa” have different run times: the photography and architecture shows end September 25, the textile and “Look Again” running until January.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.