Don’t overgeneralize the failures in Vietnam

To dismiss the Vietnam War as a total failure for the United States or a warning against any intervention may prevent us from seeing solutions to today's problems.

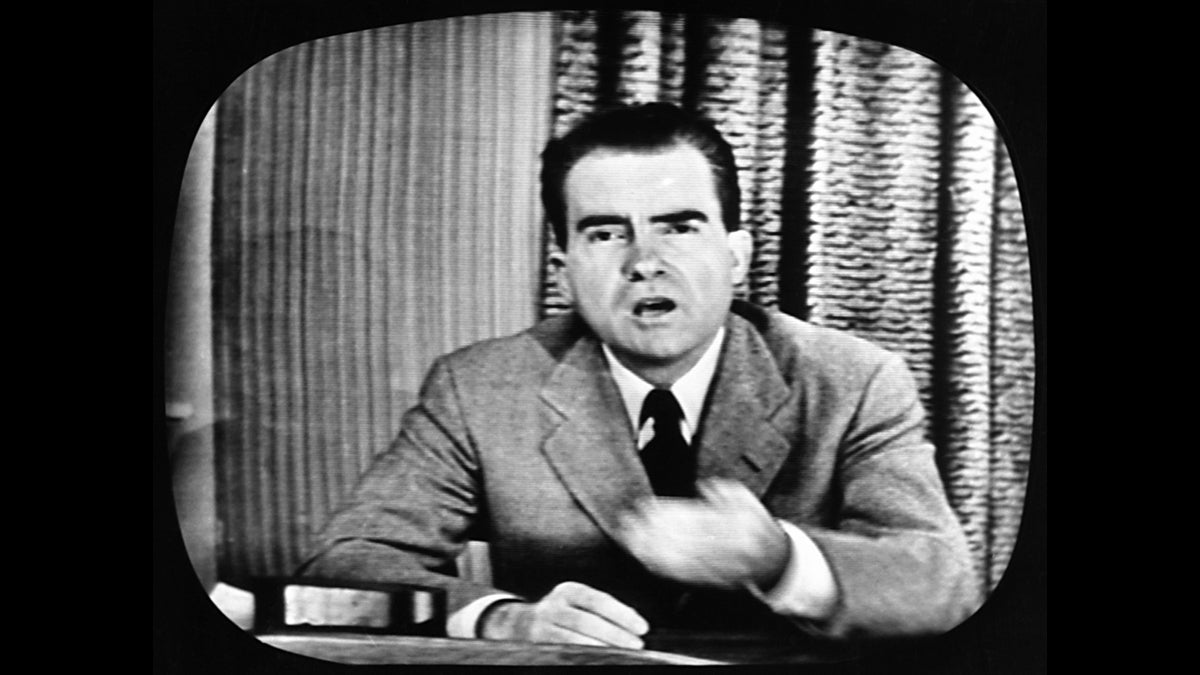

President Richard Nixon sits in his White House office after delivering a nationwide television address in Washington, April 27, 1972. Nixon discussed events surrounding his 'Vietnamization' program, saying he is withdrawing another 20,000 American troops from Vietnam by July 1. (AP Photo/Charles Tasnadi, file)

This story is part of a WHYY series examining how the United States, four decades later, is still processing the Vietnam War. To learn more about the topic, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War” running Sunday, Sept. 17 at 8 p.m. through Thursday, Sept. 28, on WHYY-TV.

—

To dismiss the Vietnam War as a total failure for the United States or a warning against any intervention causes us to lose important insight. The result may be the failure to see solutions to today’s problems.

Americans tend to equate the Vietnam conflict with failure. Indeed, the United States lost focus on why we were involved in the conflict. There were plenty of strategic and tactical blunders. Most unfortunately, Vietnam was consolidated under Communist rule.

However, to judge every aspect of the conflict a failure is an over-generalization. Successes did occur, in particular, in the Paris Peace Accords, even if we failed to capitalize on them. Effectively, the Peace Accord called for a ceasefire in place, the withdrawal of U.S. troops, the return of remains and prisoners of war, continued negotiations between the South Vietnamese government and the Vietcong, and a slow process of reunification of Vietnam through peaceful means.

The failure in the accords was a failure to enforce them, which ultimately led to the fall of Saigon.

So what lessons can be learned from the end of the Vietnam War for today’s conflicts, such as the war in Afghanistan?

Diplomacy, not unconditional surrender

The first lesson is that success in conflicts that involve insurgencies comes in the form of political or diplomatic settlement among all parties, not in unconditional surrender. The Paris Peace Accords involved the United States, South Vietnam, North Vietnam, and the Vietcong. The Vietcong, the insurgent group, was brought to the table, because any solution had to involve them.

Such an approach might be useful in Afghanistan or even in Syria, where more moderate Islamist groups would need to be part of any solution.

Military action is only one part

The second lesson is that military power is not the only solution but it is an important factor. Increased military operations under the Nixon administration kept the North Vietnamese at the negotiating table and helped with impasses during the discussions. President Nixon’s concurrent policy of “Vietnamization” (America’s gradual withdrawal) demonstrated the capabilities of South Vietnam and further helped with negotiations.

These are points worthy of reflection as we discuss American troop levels in Afghanistan and Syria and the role of local allies.

Compromise

The third lesson is a willingness to compromise. The United States conceded a ceasefire in place versus simply a ceasefire, which allowed the North to consolidate some gains. Another point worth some reflection if we think a U.S. victory in Afghanistan means no Taliban or that Syria will not have any ethnic or sectarian enclaves.

Embrace the complexities of geopolitics

The fourth lesson is geopolitics matters. Nixon’s opening of China and detente with Russia had a positive impact for the United States in negotiations. Pakistan, India, and China must be part of a solution in Afghanistan while Russia, Turkey, and Iran hold similar positions in Syria. However, such participation by other nations will never happen if other countries, both friendly and hostile, see the United States as unfocused and erratic.

Stay engaged

Finally, follow-through is important. Unlike the Paris Peace Accords, the United States must be ready to enforce any settlements that are reached. This means that isolationism or withdrawal from the world are never options.

The Vietnam conflict conjures up different memories and images for Americans. However, to dismiss the war as a total failure for the United States or a warning against any intervention causes us to lose important insight. The result may be the failure to see solutions to today’s problems.

—

To learn more, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War” running Sunday, Sept. 17 at 8 p.m. through Thursday, Sept. 28 on WHYY-TV. WHYY members will have extended on-demand access to the series via WHYY Passport through the end of 2017.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.