Blood brothers: Philly docs, researchers suck up to leeches

Listen

Robert Hicks, director of the Mutter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, holds his pet leech, Harvey. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Pharaohs, French aristocrats and wounded Revolutionary War soldiers alike have used leeches to treat all kinds of ailments. Through the centuries, the ignoble leech has been used in attempts to cure acne, to ease pain, to improve circulation.

The ancient, often revered role of the leech in medicine is not lost on Robert Hicks, director of the Mutter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

“They’re absolutely fascinating creatures,” says Hicks. “They are worms. They have no skeletons. In an anatomical chart they look like they have very few moving parts, but what they do is very sophisticated.”

Hicks has a rather unusual firsthand perspective on this. In his office, in the basement, beneath the well-trafficked exhibits of old human skulls and other preserved specimens in jars, is a fishbowl. And in it lives Harvey the leech.

“Oh, I don’t know. Don’t other people keep leeches for pets?” says Hicks.

In the basement of the Mutter Museum, director Robert Hicks shares his office with a pet leech. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

In the basement of the Mutter Museum, director Robert Hicks shares his office with a pet leech. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

‘They love my leeches’

Just about everyone who works at the museum knows about Harvey, who’s named after William Harvey, the English physician credited with discovering how blood circulates in the body.

“When people spoke about Robert before I met him, they spoke about his leeches,” says Makeba Rainey, who started working in the Mutter gift shop a year ago. She says she found it strange at first, but “it’s a normal thing now. It just adds to his character.”

Hicks got the idea for a pet leech several years ago, when visiting a restored 18th century apothecary shop-turned-museum in Virginia.

“I was charmed by the pharma paraphernalia, and in a big glass jar were two imposing leeches,” he recalls. He even got to hold them. (They were not the blood-sucking type, or the kind identified in someone’s yard in New Jersey several years ago, for that matter.)

Hicks mostly refers to Harvey as a him, but not always. Leeches are hermaphrodites.

Some leech history

Hirudo medicinales — the Latin name for the common bloodsucking species used in medicine — were thought to help with all sorts of ailments over the centuries. The compounds in leech saliva gained a kind of magic status, and leech therapy is still a thing in some places.

“Leech saliva is very chemically complicated,” says Hicks. “When the leech feeds, it secretes an anesthetic, so you don’t feel it. There’s no pain.”

Among the compounds the leech secretes is an anti-coagulant, hirudin. Scientists have actually reengineered that protein and turned it into a blood thinner.

In colonial America, leeches were notoriously used for that sometimes fatal practice of bloodletting. At the time, people thought the body was divided into four sections or fluids that had to be kept in balance. The concept was based on the ancient Greek humoral theory of the body.

If a person was sick or injured, the medical response was to drain out some of that imbalanced fluid, like blood. It was sometimes done as a preventive measure.

Doctors in the United States abandoned that theory, and with that, the leech. In recent decades, however, the leech has reappeared.

A comeback in U.S. hospitals

In the 1970s, physicians in the U.S. started turning to leeches again for microsurgery, when they had trouble reattaching a patient’s severed finger or ear, or transplanting tissue flaps from one part of the body to another during reconstructive surgery.

The veins in transplanted or reattached tissue can clog up, which means blood won’t circulate. That can lead to the loss of that tissue or body part.

Enter the leech.

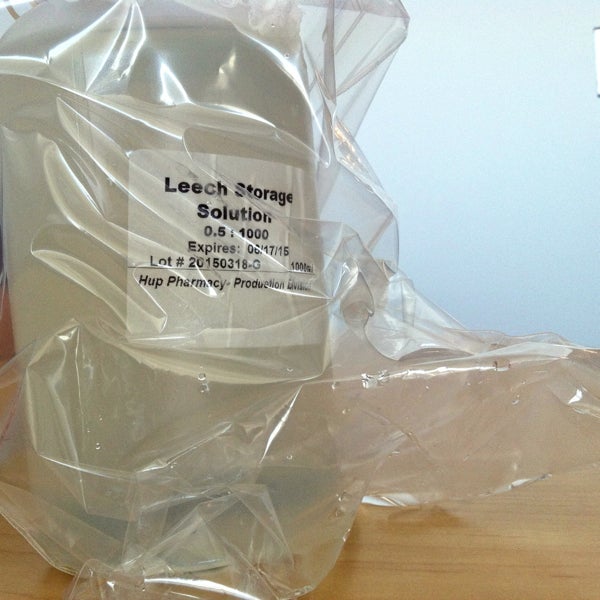

Live leeches are stored in solution in a refrigerator at the Hospital of of the University of Pennsylvania pharmacy. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

Live leeches are stored in solution in a refrigerator at the Hospital of of the University of Pennsylvania pharmacy. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

“The leech is basically the world’s most perfectly engineered blood-sucking animal,” says Dr. Stephen Kovach, a plastic surgeon at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania who occasionally orders leeches from Penn’s pharmacy, which keeps them on hand. “It’s got a mouth with three jaws and little teeth. It pierces the skin, it secretes an anticoagulant as well as an anesthetic from its mouth.”

The leech can act as a temporary vein when sucking on that tissue, circulating blood back to the body.

“Those leeches are buying time for the other veins to open up, so then can move a flap through a struggling time to a healthy time,” says Dr. James Bradley, chief of plastic and reconstructive surgery at Temple University. “The leech works well because it tends to go to a flap, and it actually will tell us if a flap is viable, if it can survive or if it’s dead.”

Bradley says leeches tend to fill up every 20 minutes. Protocol is to use one every two hours, around the clock for about two days.

There’s a risk of infection, but sometimes it’s the best option.

“Most folks, if they’re faced with losing a finger or ear or their reconstruction are pretty amenable to having a leech put on them,” says Kovach.

Since 2004, the FDA has permitted companies to breed and sell leeches for medical and research purposes in the U.S. This has also led to a wave of alternative leech therapy clinics, which use leeches for treatments beyond the FDA’s studied uses.

One company, Biopharm, distributes about 20,000 annually in the U.S., according to a company spokesperson.

Lessons in parenting

Mutter Museum director Robert Hicks is beyond thrilled that leeches have made a comeback in health care.

“It’s sort of a reminder that maybe some of these older therapies had some value that is worth investigating,” he says.

FDA approved leeches can’t be sold to just anyone, but Hicks used his own medical research affiliation to order a few for himself.

The first batch didn’t do so well.

“I had to learn good parenting skills,” he says. “My first leeches died through over-attention.”

In an attempt to make a nice home for the leeches, Hicks accidentally overcrowded the fish tank with snails. Now, it merely contains a few rocks, a ceramic skull, and a bubbler.

Harvey has thrived there for six years.

“He’s a senior citizen,” says Hicks.

Harvey’s leech companion, Hunter, named after a famous 18th century surgeon, passed away last summer.

“Harvey seemed to be more exploratory than Hunter. Hunter seemed to be more reticent,” recalls Hicks.

Hicks checks on Harvey weekly. The leech has developed a tumor protruding from one side that’s of slight concern.

When Hicks picks him up, Harvey shape shifts and quickly slivers all over Hicks’ hand, occasionally pointing a sucker into the air. (Leeches have suckers on both ends, jaws on just one.)

Leeches have suckers at both ends, but jaws at just one. Harvey clings to Hicks’ palm as he explores. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Leeches have suckers at both ends, but jaws at just one. Harvey clings to Hicks’ palm as he explores. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Hicks learned the hard way that he has to keep a close watch when Harvey is out of the water. One time he thought he’d put Harvey back but didn’t notice Harvey had instead accidentally slid down the side of the bowl.

“Five days later, I’m sitting at my computer and I’m aware of a movement on the floor to my right on the carpet, and there’s Harvey, inching over,” he recalls of the then desiccated leech. “And I can almost hear him say, ‘Help me!’ I felt just awful … Another day or two, he would have had it.”

For the most part, this living marvel of nature, a symbol of thousands of years of medicine, spends the majority of its time hidden away, burrowed in rocks in this fishbowl beneath the museum.

But Harvey does make a special appearance every eight months or so, one that Hicks invites new museum staff in to observe. That’s when it’s feeding time … on Hicks’ forearm.

“It builds an interesting relationship of person to leech,” says Hicks. “I find myself listening with a strange interest when young mothers talk about nursing babies. There’s a resonance there.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.