North Carolina’s fight over black votes is just the beginning

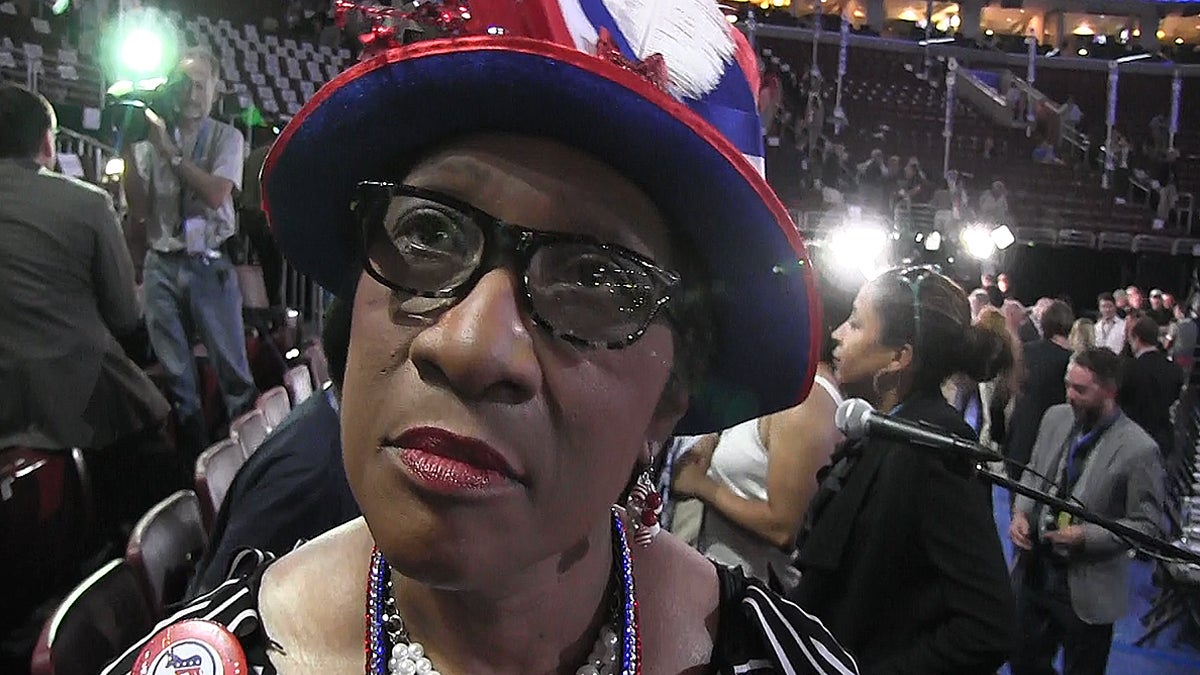

North Carolina delegate Gloria Baker Goodwin at the Democratic National Convention (Solomon Jones for NewsWorks)

When I learned that a three-judge panel of the Virginia-based 4th Circuit Court of Appeals had struck down North Carolina’s restrictive voting law, I didn’t think of Rev. William Barber, the firebrand North Carolinian who electrified the Democratic National Convention with his call to revive the heart of our democracy.

I thought of Gloria Baker Goodwin, a delegate from Onslow, North Carolina who I’d spoken to several days before.

Baker Goodwin, a bespectacled woman wearing a sequined red white and blue hat, spoke softly when I asked her about the restrictive new voting law that her native state put in place after the Supreme Court scuttled the Voting Rights Act. But her words hit hard.

North Carolina’s voting law was “a form of racism,” she said. In an 83-page opinion, the federal appeals court agreed.

The law not only implemented a strict Voter ID requirement. It also eliminated same-day voter registration, cut early voting by one week, disallowed pre-registration for high-school students about to turn 18, and banned out-of-precinct voting.

Those provisions of the new law, wrote Judge Diana Motz of the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, “target African Americans with almost surgical precision.”

But while I’m pleased the court saw through the racial targeting that was so apparent in North Carolina’s new voting law, I know the fight over black voting rights in North Carolina and other states continues. That’s because legislators in North Carolina’s GOP-dominated state legislature went beyond restrictive voting laws. They also used the redistricting process to target African Americans.

Redistricting, a federally mandated process designed to ensure that congressional districts accurately reflect population shifts, is a good thing when it’s used correctly. In North Carolina, however, the redistricting process has long been seen as a form of gerrymandering. That is, drawing district lines in ways that unfairly disenfranchise entire groups. In this case, the group was African Americans.

In 2011, in a state that was evenly spilt between Democrats and Republicans, North Carolina Republicans redrew district lines so that Republicans controlled 10 of 13 congressional seats. That was challenged in federal court, and in February, the GOP-dominated state legislature took another crack at it.

The new lines preserve that 10-to-3 split, and critics say they continue to disenfranchise black voters.

Gloria Baker Goodwin, the Democratic delegate I spoke to at the Democratic National Convention, is among those critics.

“I think it’s a way to disenfranchise particularly voters of color,” Baker Goodwin said of the redistricting plans. “I think it was a way to snuff out the delegates and the ones that were running for office in those districts to provide us as people of color to be disenfranchised to keep us from voting.

“I am a precinct chair in my area, and the way they ran the different demographics from my area completely took my people out of my precinct area. So to me I thought it, to me, was a form of racism and a form of really allowing the other party to have the upper hand.”

Ironically, the U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to review North Carolina’s redistricting plan to determine if it relied too heavily on race in determining district boundaries. That’s because two of the congressional districts in the 2011 plan were apparently designed to remain majority black.

Even with two majority black districts in place, however, it’s clear to me that North Carolina state legislators were not trying to help black voters. They were trying to isolate and disenfranchise them. But North Carolina is not alone in doing so. In fact, the pattern there is a microcosm of the truth around voting rights in America.

In spite of–and in some ways, because of–the progress African Americans have made in the political process, there are some in the GOP who would rather stop blacks from voting than try to appeal to black concerns.

That’s odd to me, because black concerns are very similar to those of other voting blocks. We are concerned about jobs, about national security, about education, and about fairness. We are concerned about an equal distribution of resources. And like everyone else, we are concerned about equal treatment under the law.

We address those concerns not only by exercising our Constitutional rights through activism and protest. We addess them by exercising our right to vote.

Those who would deny us our rights know very well the power of voting.

That’s why they try so hard to stop us.

That’s why we can never let them.

Listen to Solomon Jones weekdays 7-to10 am on 900 AM WURD

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.