New Princeton exhibit captures the social upheaval of the 60s & 70’s in 3 American cities

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Steve Hamburger and Vera Tims met in Lakewood, New Jersey's Tent City (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

-

-

-

In the 1960s and ’70s, residents who could afford to were fleeing cities. Chicago, Los Angeles and New York were congested, smelly-smoggy-dirty, crime-ridden, and rife with bureaucracy and inefficiency. White people feared black people and fled to newly developed suburbs, enabled by the automobile. At the same time there was a fomenting in the streets — mass protests, marches and demonstrations over civil rights, anti-war sentiment, women’s liberation, and the beginnings of the environmental movement.

The City Lost and Found: Capturing New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, 1960–1980, on view at Princeton University Art Museum Feb. 21 through June 7, explores artists’ impressions of American cities in crisis. More than 150 objects—including photographs and films, architectural renderings and planning documents, posters and periodicals, drawn from more than 40 collections across the country—expose the challenges and unrest of the era, and offer new possibilities for American cities.

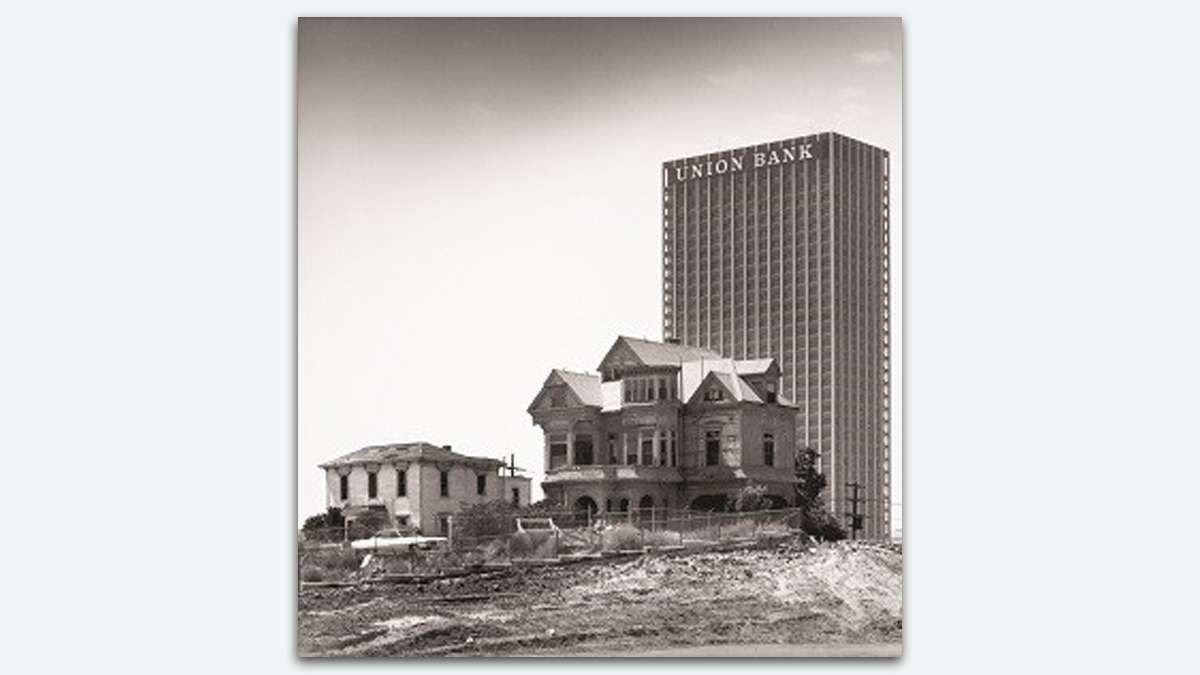

Photography and film not only expose the conditions of crisis but present a vision for the future of American cities. The City Lost and Found uses, as a starting point, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” by Jane Jacobs, written in the early ’60s when planners believed that wholesale reconstruction and the building of high rises was the best way to save the city. Jacobs held a different view. She saw life in those old neighborhoods, in their diversity, the narrow streets where children could play, and argued for their preservation. But in the name of eradicating “blight,” urban renewal often meant the demolition and erasure of entire neighborhoods.

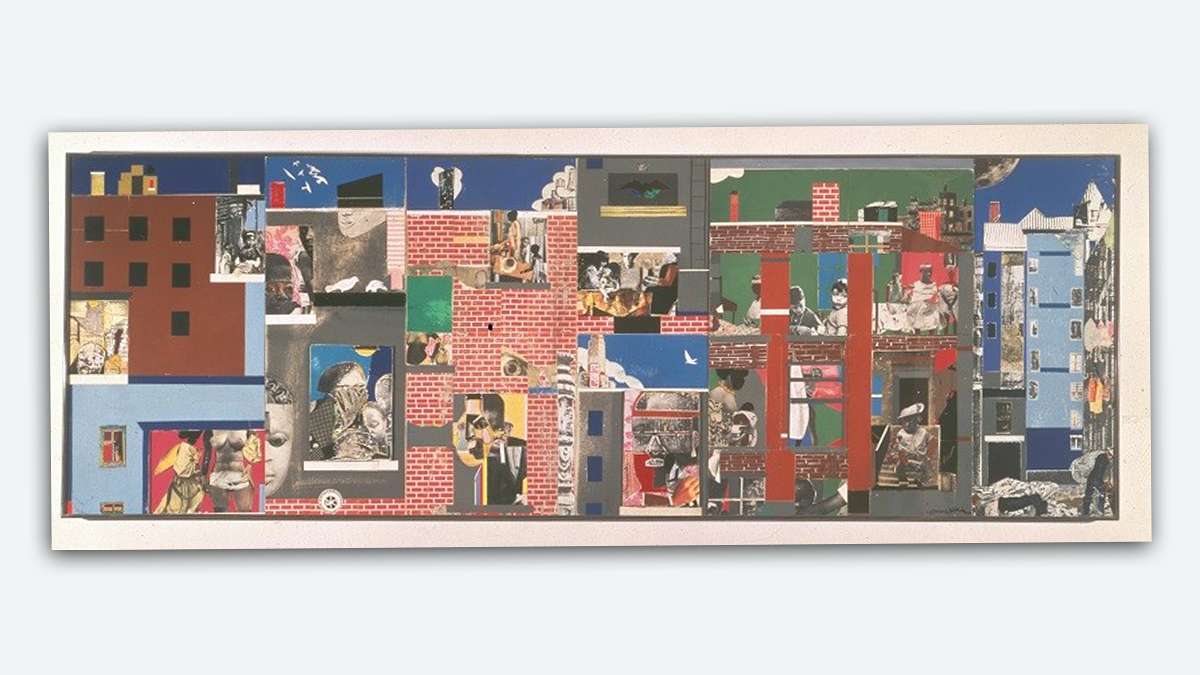

Romare Bearden’s 18-foot-long collaged mural of a block of Lenox Avenue in Harlem is a colorful depiction of one such neighborhood. It includes a liquor store, a barbershop, a church and a funeral parlor, as well as a corner grocery store. People walk along the street, play on the sidewalk, sit on the stoops in front of their homes – indeed they turn the stoop into a living room, the sidewalk into a playground. When it was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in 1971, Bearden’s mural was accompanied by a soundtrack of jazz and church music, children laughing and playing, news broadcasts and the general cacophony of city life.

On the darker side, Bruce Davidson’s Chromogenic print shows straphangers inside a graffiti-laden train seen through subway dredge-streaked windows. This graffiti was not yet the new urban art, this graffiti was the angry expression of disenfranchised youth. The straphangers look down, off into the distance, or close their eyes entirely to block out this bleak existence, perhaps dreaming of a better place, a better time.

What cities lost during the two decades covered in The City Lost and Found are “a sense of how cities worked and how they served their constituents,” says Curator Katherine A. Bussard. That message was heard loud and clear in the protests of the ’60s. “It showed what was lacking, and how cities underserved their population with housing, empowerment and civil rights.”

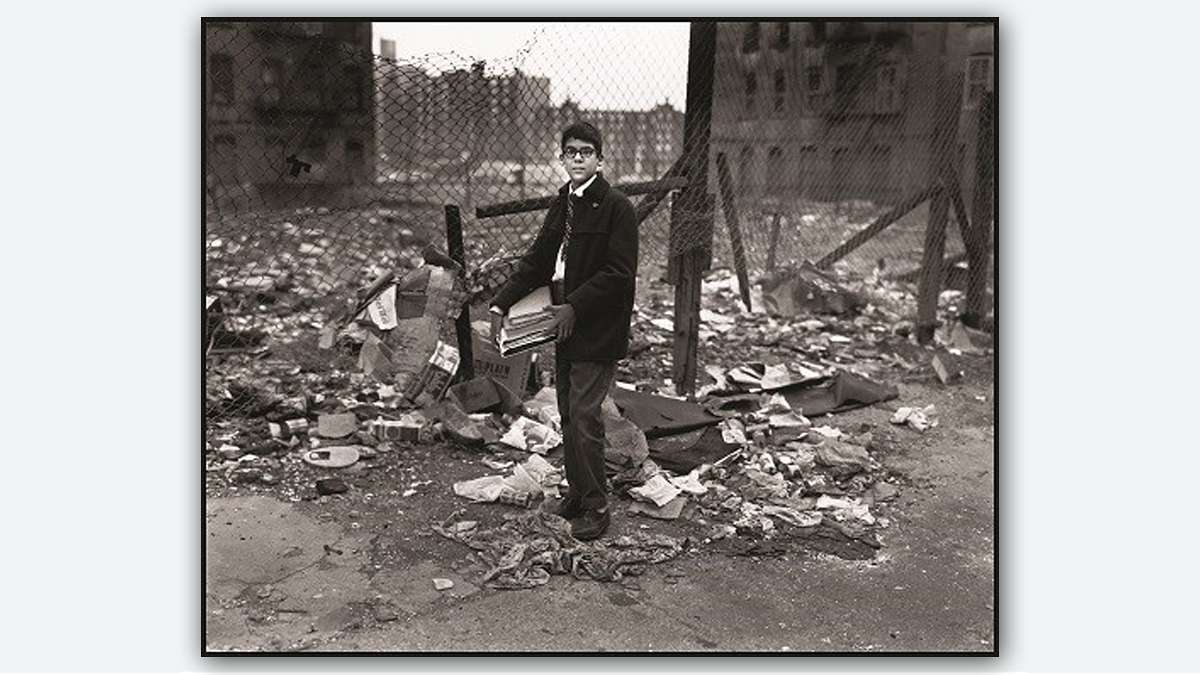

The Nov. 1, 1968 cover of TIME Magazine featured a beleaguered Mayor John Lindsay over a collage of tumbling buildings, designed by Romare Bearden, with the headline “New York: The Breakdown of a City.” Lindsay is also pictured leading a group of men through trash-laden streets in an AP newswire photo during the city’s Sanitation Workers’ Strike in 1968. Trash piled up at the rate of 10,000 tons a day.

Seven years later, New York nearly went bankrupt. In that year, Andy Blair made a haunting photograph of a ravaged car picked clean of anything of value, abandoned on the West Side Highway. It looks like it has been there forever, and yet how could it have been left on such a busy highway? How did it get there in its condition, so old, so dilapidated, so stripped bare?

Once abandoned, cities made an attempt to shift their thinking toward restoration and revival. Perhaps it was time to consider Jane Jacobs’ view of neighborhoods being a vital part of renewal.

Jacobs was part of the battle to save New York’s Penn Station from demolition – she is pictured in front of the McKim, Mead and White Beaux Arts architectural jewel before it was razed in 1963 to make way for Madison Square Garden. While that effort failed, it galvanized citizens and begat the historic preservation movement and the creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

We may not be able to replace the great buildings and neighborhoods that have been lost, but through photography and film they become part of the permanent record. Photography and moving image are also important to inspiring preservation, says Bussard.

When the city was supposed to be on its way out from urban despair, a slew of New York disaster films were released. In the 1973 dystopian film with Charlton Heston and Edward G. Robinson “Soylent Green,” it is the year 2022. New York City is up to a population of 40 million and people sleep on top of one another in staircases. Homeless people fill the streets, the oceans are dying, there is year-round humidity due to greenhouse gases, and people subsist on processed food rations made of plankton by the Soylent Corporation.

A mobile-friendly website featuring maps of particular pockets of creativity in each city has also been created.

There will be an opening night keynote lecture, a seven-week film series and a symposium with presentations by the curators, artists and leading scholars from a variety of disciplines, including urban studies, film, architecture, urban planning and art history.

________________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.