New exhibit at Woodmere chronicles life’s work of centenarian artist

'Theresa Bernstein: A Century in Art' will be on view at Woodmere Art Museum from July 26 to Oct. 26. (Courtesy of the Woodmere Art Museum)

When she discovered Theresa Bernstein — a little-known but important American artist whose work is coming to Woodmere Art Museum — Baruch College and City University of New York professor Gail Levin admired Bernstein’s realist paintings of immigrants, workers, and suffragists in the early 1900s.

But the surprise was that Bernstein, whose life took place in three centuries, was still alive and painting in New York City in the 1990s.

A woman overlooked

“From the minute I walked into Woodmere as director, I felt that Theresa Bernstein was a sitting duck for a great exhibition,” Woodmere director and CEO William Valerio told NewsWorks the week before “Theresa Bernstein: a Century in Art” was slated to arrive in Chestnut Hill.

Valerio said Bernstein (1890-2002) was “truly one of the greatest artists of the 20th century,” despite the fact that she has been mostly forgotten outside of art circles since her death at age 112 in New York.

In Valerio’s opinion, “there’s no question that her being overlooked has to do with her being a woman in the context of a male-dominated art world…and the fact that she was a person of the Jewish faith.”

From Kraków to Philly to New York City

Woodmere curator of education, Hildy Tow, can provide fascinating details of Bernstein’s long life.

The artist grew up in North Philly after immigrating from Kraków, Poland — where she was born — when she was one year old.

According to Tow, Bernstein’s “educated, cultivated” parents provided both a religious and secular education, and encouraged their daughter’s artistic pursuits.

She went on to attend Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art) on a scholarship, and in 1911, her family’s business brought them all to New York City when she was 21.

Bernstein lived with her parents in Manhattan but rented her own historic slice of the New York art world at the Holbein Studio at 145 W. 5th St., located above a stable for affluent city-dwellers’ horses. John Singer Sargent and Cecilia Beaux are among artists who also rented studios there.

‘Painting like a man’

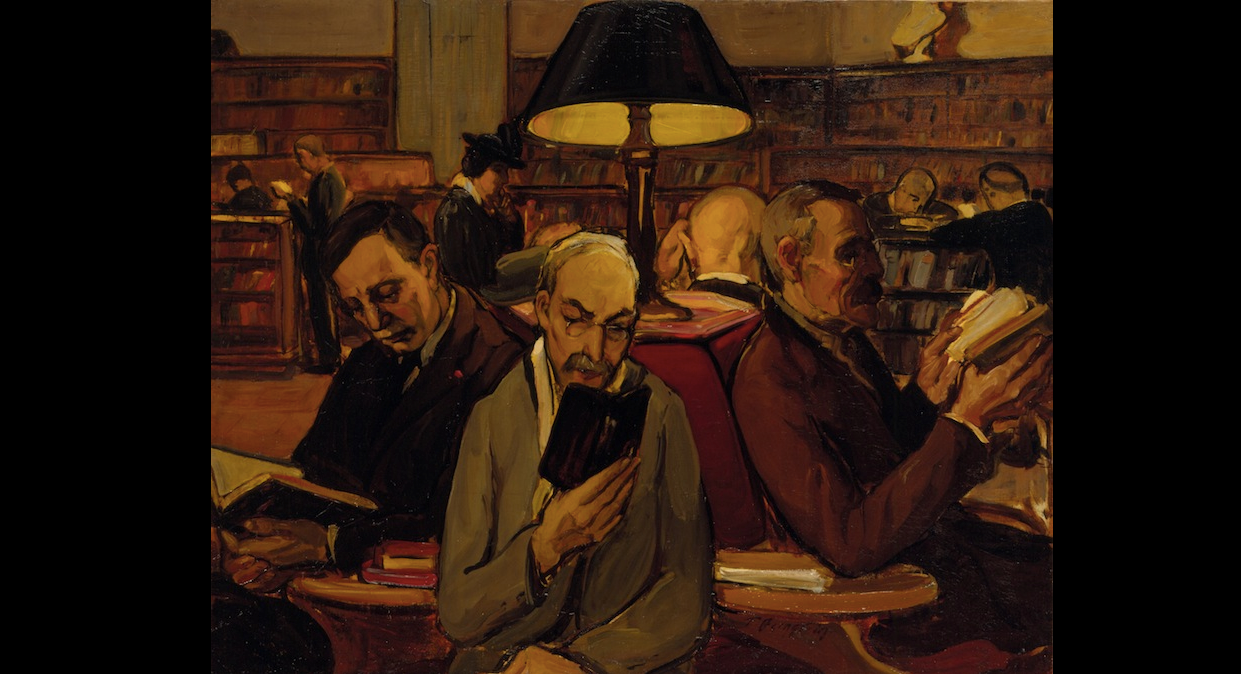

Tow and Valerio explained that Bernstein followed a group of artists known as the Ashcan painters, who took a different approach to art than many of their impressionist contemporaries. In the realist tradition of Philadelphia icon Thomas Eakins, the Ashcan painters captured the streets and daily life of the city.

“She exhibited with them in the same galleries, but she was never quite embraced as part of the group,” Valerio added.

“Her paintings were just as strong,” Tow said of Bernstein, noting that during her lifetime, she actually was better known than her friend Edward Hopper, a famous name today.

In 1914, Bernstein painted “The Suffrage Meeting” after sketching at the actual events alongside women’s rights heroes like Lillian Wald, actress and singer Lillian Russell, and League of Women Voters founder Carrie Chapman Catt.

She was “out on the street, and she’s inspired by listening to these women speaking their minds,” Tow said, but Bernstein faced her own challenges.

She was an acclaimed artist, but when her work was reviewed alongside that of her male colleagues, “she was praised, but she was praised for painting like a man.”

“She loved painting people in their environment,” Tow continued, explaining that Bernstein would often sketch in the streets, or at meetings, concerts, or religious services, and then use members of her family as models to fill in the details of her paintings.

Not everyone liked seeing a woman sketch public events in that era, Tow said. According to Bernstein’s journal, when she was working on sketches for 1916’s “Polish Church: Easter Morning,” someone took offense, and “threw down her papers.”

But the artist wasn’t deterred. “She just continued sketching…she had this kind of vitality and confidence to just be in that environment and do what she needed to do,” Tow said.

Einstein and ‘The Immigrants’

For Tow, one of Bernstein’s best paintings, which will be on display at the Woodmere show, is 1923’s “The Immigrants.” It shows the deck of a ship teeming with new arrivals to the U.S., a mother and baby dominating the foreground.

The piece is even more poignant when you know that Bernstein painted it about a year after she and her husband, William Meyerowitz, lost their own infant.

Bernstein would receive commissions to paint portraits throughout her life, including celebrities like Louie Armstrong and Cab Calloway.

Another notable moment in her career came in 1921, when she and Meyerowitz were invited to make portraits of Albert Einstein during America’s first Zionist meeting, held in New York. Now, her work is in the collections of institutions like the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and many others.

Bringing Berstein home

Gail Levin, a professor of art history, American studies, and women’s studies, organized the exhibit after research on Hopper led her to Bernstein. Levin met Bernstein for herself when the artist was in her 90s.

The current traveling exhibition and catalog features paintings made between 1912 and 1972

Valerio said Levin was “thrilled” to bring this show to Woodmere, the exhibition’s only stop in Philadelphia.

“Theresa Bernstein: A Century in Art” will be on view at Woodmere Art Museum from July 26 to Oct. 26. For information on special events, including a free open house and lecture from Gail Levin on Sept. 13, visit the Woodmere’s website.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.