N.J. has the most affordable-housing units exposed to sea-level rise, report says

Atlantic City, Hoboken and Camden among the most vulnerable to climate effects.

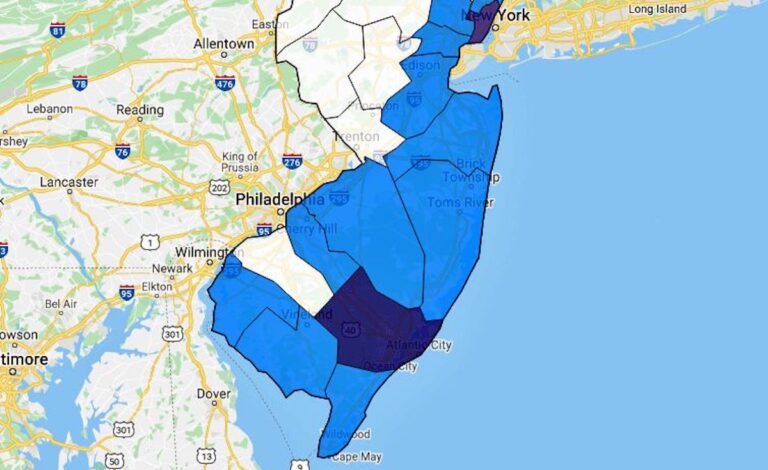

Colors on the map indicate the number of housing units likely to be flooded: dark blue = 2,141 or more, dark lavender = 1,071 – 2,140, medium blue = 1 – 1,070, white = 0. (Climate Central)

This story originally appeared on NJ Spotlight.

New Jersey has the largest number of affordable-housing units exposed to sea-level rise among all coastal states and can expect that number to surge as waters climb in the next 30 years, according to a new report led by a Princeton-based research group.

In the first national assessment of how affordable housing will be affected by sea-level rise, Climate Central and its partners estimate that New Jersey currently has 1,640 affordable housing units that are subject to coastal flooding at least once a year, according to the report released on Tuesday.

That is already the highest in the country, and by 2050, the number is expected to increase more than four times to 6,825, or 3.7% of total affordable-housing stock, as seas rise under a scenario of high global-carbon emissions, the report said. That compares with about 5,300 and 4,800 in New York and Massachusetts, respectively, which have the next-highest totals of affected units.

Poorer residents at highest risk

The report adds detail to the reality for many coastal communities: Those who can least afford it are often the most vulnerable to the harm from climate change, in this case rising sea levels.

“While people and assets in virtually all coastal areas face some degree of risk from coastal flooding, the exposure of low-lying affordable housing is of particular concern,” wrote the report’s authors, recommending further planning efforts to protect these residents.

The report is based mostly on properties identified by the National Housing Preservation Database, an inventory of federally assisted rental housing. It also includes some state-subsidized properties, and nonsubsidized buildings that are likely to rent at below market rates.

Ranked by city, New Jersey would also have some of the hardest-hit communities in the country, the report shows. It named Atlantic City, Hoboken, Camden, Penns Grove and Salem in the 20 cities nationwide with the largest number of affordable-housing units that would be flooded by rising seas at least once a year — a bigger share of the top 20 cities than any other state.

Bad news for Atlantic City

In Atlantic City, 3,167 affordable units, or 52% of the total in that category, would be exposed by 2050, giving it the second-highest rate of any coastal city after New York, the report said. By the middle of the century, the city’s projected number of flood-prone affordable properties is expected to be more than 400% higher than in 2000.

The five New Jersey cities are “of particular concern,” the report said, because they are poor cities, with a high proportion of people of color, where the median income is only half of the national figure, and so they have relatively high demand for affordable housing.

“This extensive exposure in multiple cities could put a major strain on the state and is particularly concerning since many affordable housing units in New Jersey are still being rehabilitated” even eight years after Superstorm Sandy, said the report, which was written in conjunction with the University of California at Berkeley and the National Housing Trust, a nonprofit that preserves, expands and revitalizes affordable housing.

It called for significant resiliency planning such as elevating buildings or constructing sea walls in affected communities to protect residents of affordable property, whose economic challenges could multiply if their homes are flooded.

“Inaction could result in high risk for residents who may lack access to sufficient resources to prepare and recover from flooding impacts,” it said.

Physical, financial or regulatory measures in key locations could help many people avoid the flooding that’s expected to worsen in coming years, the report said.

Floods could reach inland cities

Projected flooding may also affect inland cities such as Vineland if they are low-lying and are connected to coastal waters that can or are not prevented from moving inland during flood events, the report said.

Sea level at the Jersey Shore is expected to rise by between 0.9 feet and 2.1 feet from 2000 to 2050, according to a 2019 report from the Department of Environmental Protection and Rutgers University. Beyond 2050, seas at the Shore are expected to rise as much as 6.3 feet from their 2000 level if global carbon emissions are unrestrained by policy, and by 4 feet even if emissions are cut to low levels.

Although the new flood projections are based on a high-emissions scenario, they would be very similar if based on significant global carbon cuts because the amount of sea-level rise is essentially baked in until 2050, regardless of any policy actions, scientists say.

The report defines affordable housing as that which costs occupants not more than 30% of gross household income. Its availability for the poor has declined in the past decade as rents have risen by 25% while wages have largely stagnated, resulting in a majority of poor families paying more than half their income on rent, while a quarter pay more than 70% on rent, leaving little for other necessities, it said.

With housing that is typically substandard, the poor are especially at risk from coastal flooding, the report said.

Poverty and climate change

In May, the New Jersey Climate Change Research Center, a Rutgers group, identified poverty and other factors as heightening the vulnerability of certain residents to climate change. Groups including communities of color, immigrants and seniors, especially those living in flood plains, are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change, the Institute said in “A Seat at the Table,” a report on how to integrate those groups into coastal hazard planning.

The Climate Central report said it provides a more precise estimate of the number of affordable properties affected, and the expected frequency of flooding than do previous studies. It uses a geolocated inventory of individual building footprints whereas earlier calculations have been based on housing-density data, a relatively imprecise measure. It’s also based on a range of flood scenarios, allowing a more detailed projection of risk, in contrast to earlier studies that have been based on a limited number of scenarios.

Together, the new techniques not only identify the buildings that are at risk but calculate the number of times they are likely to be exposed to floods, the report said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.