When Christiana High school hosted Conrad Schools of Science in football on a Friday afternoon in September, the scene was a microcosm of the state of affairs in the Christina School District.

Christiana, a National Blue Ribbon school in the 1980s, had just 25 players – less than half of a typical varsity team. And in the home stands, only about 50 people rooted on the Vikings.

By contrast, Conrad had a large team and band, and a couple of hundred fans. The visitors rolled over Christiana 34-0.

The lopsided score was more than a shellacking on the gridiron. It illustrates the exodus of students from the Christina district to others in New Castle County as well as charter schools.

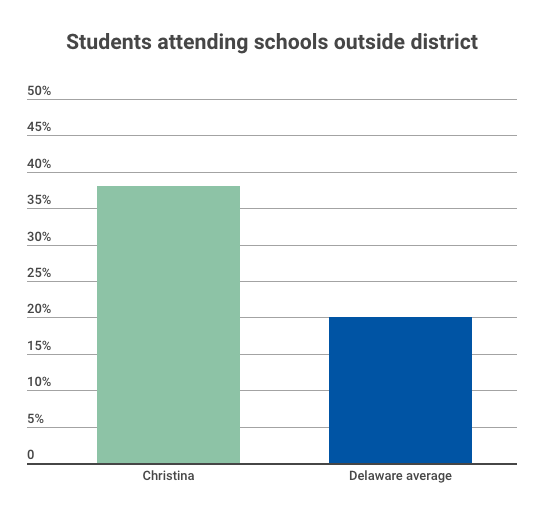

A total of 8,700 students from the Christina district attend non-district schools. That’s 38 percent — far more than any other district.

Each year, there’s more empty seats at Christina schools, as parents are increasingly “choicing” into other districts, or picking charter or vo-tech schools, according to state and school district data analyzed by WHYY.

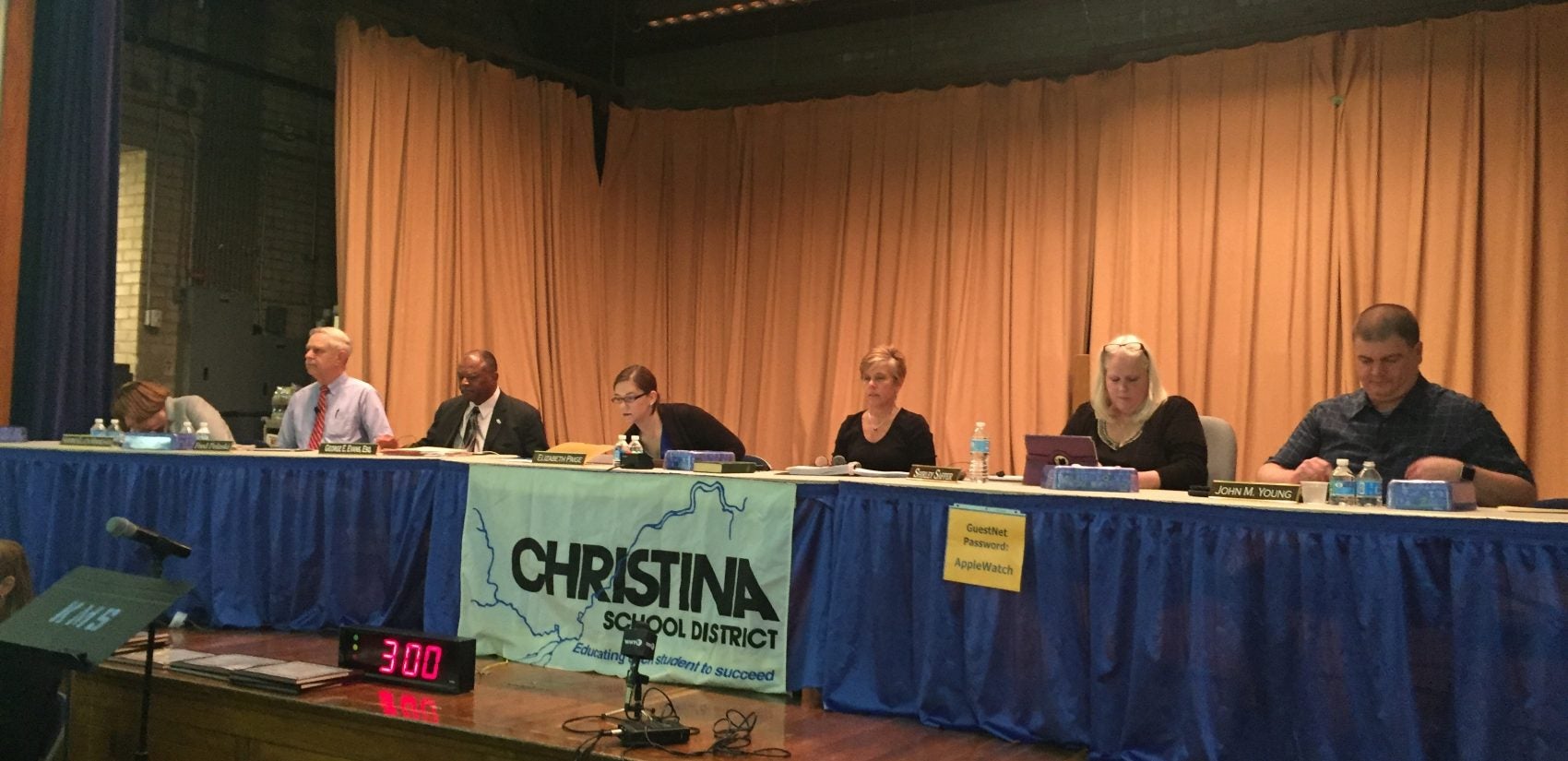

Elizabeth Paige, a Christina school board member who served as board president until recently, said the ever-rising number causes her and others on the board and across the district deep concern.

“We definitely have capacity in our buildings,” Paige said. “There’s conversations that that have been going on for a long time now about the issue.”

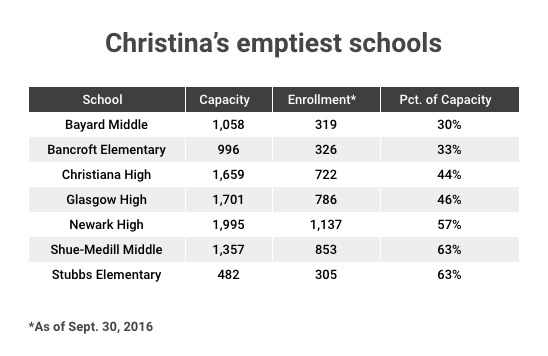

District’s three high schools are half-empty

The exodus is most alarming at the district’s three high schools, Christiana, Glasgow and Newark.

Together, they are at less than half capacity, with 2,600 student seats unfilled.

You could close Christiana High, for example, and send its 772 students to the other two schools, and still have more than 1,000 empty chairs.

Tricia Stallings, whose son is a Christiana freshman this year, was stunned by its emptiness. Before the family moved to the district, he was headed to Colonial’s William Penn, which has nearly 2,100 kids.

“When we brought him here to Christiana, I figured it’s probably the same amount and they said it’s only 700 students,’’ Stallings said. “That’s a huge difference.”

Closing a high school with a proud tradition or mothballing other schools, as dramatic as such an action might sound, isn’t out of the question.

The flight from Christina schools is causing policymakers in and out of the district to begin talking about shuttering low-capacity buildings, which are aging and cost millions of dollars a year to maintain.

The district recently began conducting a capacity analysis, something board member John Young unsuccessfully tried to get members to authorize in January.

“The capacity of our buildings is something I’ve been trying to address for a little while now,’’ Young said. “If you don’t have the students in the schools, you don’t have the money to offer the program diversity.”

Young said he will closely monitor the capacity analysis.

Should the research show “that we could offer better programs for kids, then I think closure could be something we could or should look at,’’ he said.

Gov. Carney: District ‘will have to make hard decisions’

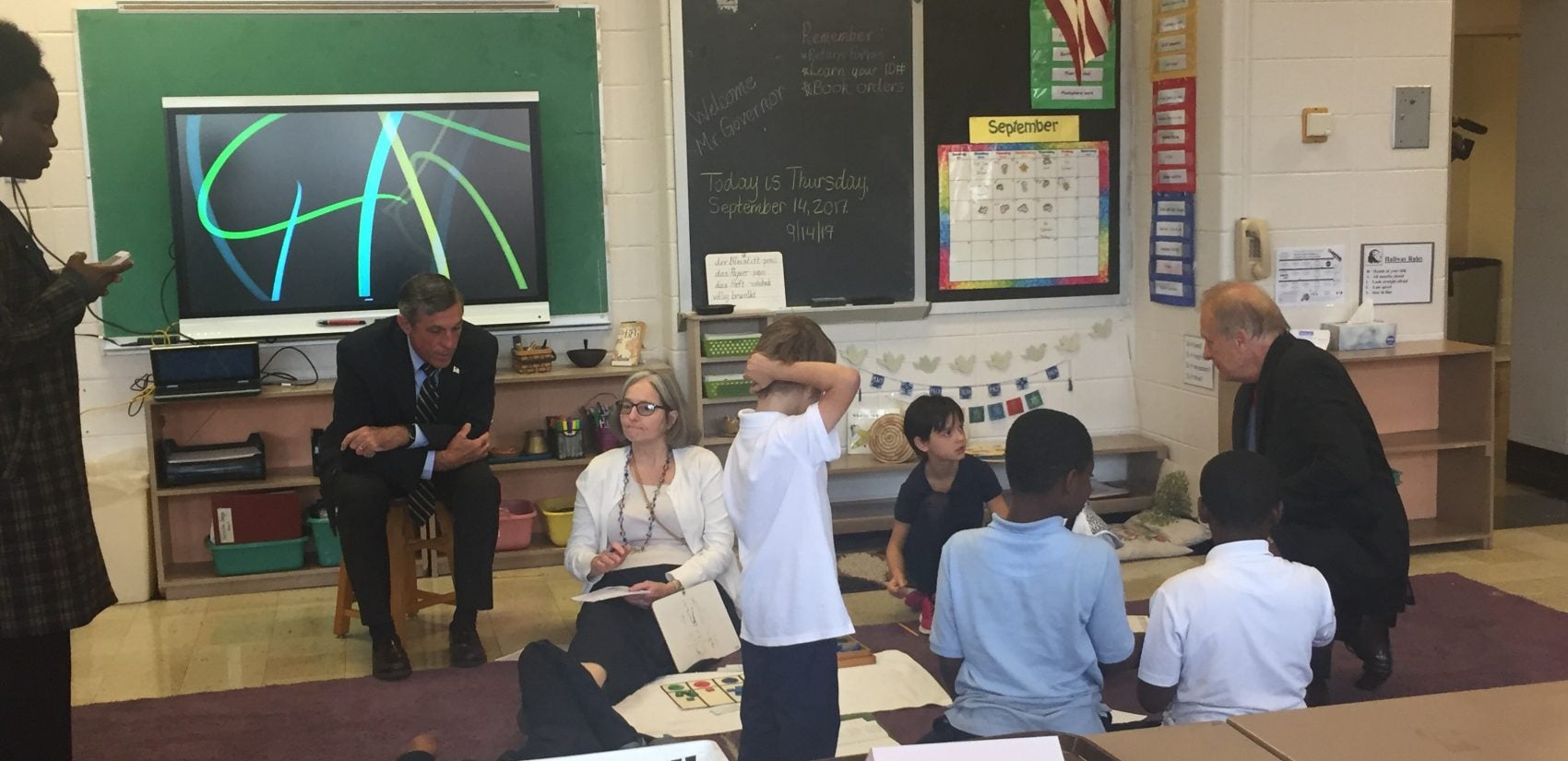

Gov. John Carney recently toured Christina’s Bancroft Elementary School and Bayard Middle School, which are both barely 30 percent full.

Carney’s visit with new Christina superintendent Richard Gregg and other top education officials, including state Education Secretary Susan Bunting, was part of his mission to turn around high-poverty, low-performing schools in Wilmington.

But the governor talked with WHYY about the departure of students from Christina, saying Gregg had spoken to him about the accelerating loss.

“The Christina board and administration will obviously have to make some hard decisions,” Carney said. “Obviously nobody likes to close schools. But you don’t want buildings to be half full and that’s a real challenge for us.”

Carney met with the Christina board on Oct. 3 during a public workshop to present a framework for a partnership to improve district schools.

Carney wants the proposed alliance to:

• Give principals more control over how their schools operate;

• Empower teachers in high-poverty schools to have more say in how resources are used;

• Address the need to improve achievement rates in Christina’s five Wilmington schools, which he called “among the lowest in the state.” At Bayard, for example, only 3 percent of students are proficient in Math, and just 5 percent in English;

• Creating “trauma-informed classrooms’’ to address the issues faced by many Christina students from Wilmington, which has been reeling for years from an epidemic of gun violence;

• Build systems to create meaningful, sustained change in the district’s five Wilmington schools by launching a two-generation network to support infants, toddlers and adults.

His goal? Break the cycle of “generational poverty.”

The Carney administration and the district also signed a letter of intent this week develop a Memorandum of Understanding, which must be approved by the school board, to implement in the 2018-19 school year.

Carney also tackled the capacity issue in his remarks, saying “serious conversations” are needed.

“We are doing our students, educators, and taxpayers a disservice when we have half-empty school buildings — needlessly spreading resources thin,” the governor said.

Superintendent: “not ready to give up any of our buildings’

WHYY attempted to interview Gregg on camera about the student drain in August, before this school year began.

But Gregg, a Glasgow grad who took over the district in April, declined our request for an on-camera interview after several attempts. District spokeswoman Wendy Lapham emailed a statement that mentioned the capacity study.

“The district will be engaging our community in a process this fall that will include a review of all facilities and school capacities, the development of strategies for attracting and retaining students, and plans for designing and implementing relevant career pathways,’’ she wrote.

Gregg “has shared with the board that he considers underutilized buildings a challenge for the district, and will be working with staff and the community to identify the most effective use of buildings to maximize resources for students,’’ she wrote.

Superintendent Gregg spoke briefly to WHYY off camera while he toured Bancroft with the governor. While walking the hall of the underutilized school, Gregg stressed that he is focused on finding ways of attracting students back to Christina’s schools, rather than looking to shut the doors.

“I’m not ready to give up any of our buildings,” he said.

The district also denied a request to let WHYY visit any of the three traditional high schools, rejecting our request in early September to have the principals escort us through the buildings. The principals “are focused now on getting the new school year off to a great start,’’ Lapham wrote.

The district’s response about their problem with emptying buildings mirrored their reaction this spring when WHYY reported about the mothballing of their libraries at middle and high schools and elimination of librarian positions.

Gregg and principals did not agree to requests for interviews, nor was WHYY allowed to see the libraries.

Christina won’t provide costs to maintain schools

The district also refused to cooperate with attempts to determine how much it costs taxpayers to maintain even one of the high schools.

WHYY first tried to get an estimate from Lapham or chief financial officer Robert Silber. We asked that the district include costs such as insurance, utilities, electronics, custodial staff salaries and benefits, plus cost of renovations such as roofing, windows, stadium upgrades and other costs such as lawn care.

In her written response, Lapham said “trying to get the information together has been a bit challenging’’ at the start of the school year, “but I will get it.”

Days later, she said Silber directed her to have WHYY file a Freedom of Information Request for the information.

WHYY filed an official FOIA request for the cost in 2016 to maintain Christiana High, including custodial staff, utilities, and upkeep and renovations, such as replacement of roofs or windows and the heating systems.

Again, this was denied, even the salaries of top administrators – facts government agencies routinely provide without question.

“There are no reports that provide the information you request,” the district wrote.

WHYY plans to appeal Christina’s denial to Attorney General Matt Denn’s office.

Young doesn’t have the cost information, but said the expense of maintaining underutilized schools, especially aging ones, is high and that taxpayers should be concerned about how Christina is spending their money.

“The costs I would say are prohibitive … would say certainly close to at least a million or more per school” annually, he said.

Young said that beyond equipment costs and custodians, “there’s a lot of support staff that makes a school run.”

8,700 Christina residents in charters, other districts

So where are the 8,700 students who left Christina going?

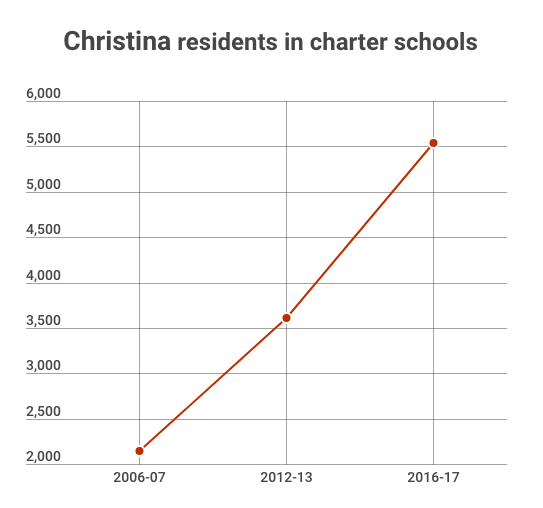

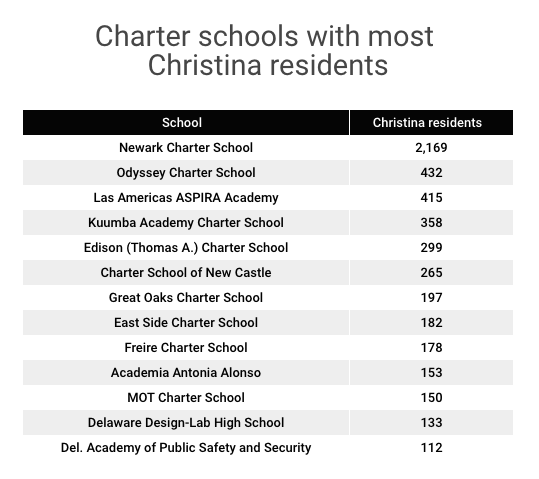

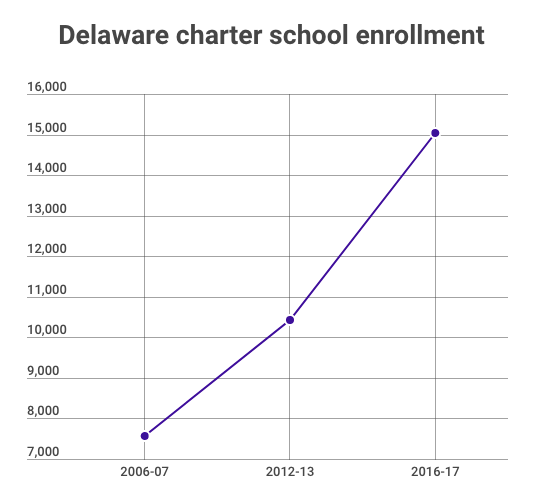

Beyond vo-tech and out-of-district choice, the primary reason Christina’s enrollment has shrunk is the exodus to some 20 charter schools – 5,537 students in all – nearly triple the number 10 years ago.

Kendall Massett, president of the Delaware Charter Schools Network, said parents opt out of Christina and other districts because parents are discovering options not found in traditional public schools.

“When the kids are leaving Christina, parents are choicing their kids into a different school. They are going toward something that works for their kid,’’ Massett said.

“Some kids don’t do so good in those big comprehensive high schools. They thrive in a smaller, more family-like setting.”

The biggest recipient of Christina students is National Blue Ribbon winner Newark Charter, with 2,200.

Newark Charter, a kindergarten through 12th grade school, pulls from a five-mile radius that encompasses many of Christina’s more affluent areas. Newark Charter has been criticized for not taking students from the entire district, including Wilmington.

But the bottom line is that 2,200 Christina parents have their children at Newark Charter, with thousands more on the waiting list.

Another 3,300 students who live in Christina attend other charter schools that many members of the public don’t know about.

About 1,200 go to five charters in Wilmington – Kuumba, Edison, Great Oaks, East Side and Freire.

More than 400 apiece go to Odyssey near Wilmington and Las Americas ASPIRA near Newark. Charter of New Castle, formerly known as Family Foundations, has about 300.

Gateway Lab, Delaware Design Lab and the Delaware Academy of Public Safety and Security each have about 100 Christina students.

Nearly 200 attend MOT Charter in Middletown, more than 10 miles from Christina’s southern border, and First State Military near Smyrna, some 25 miles away.

The flight from Christina is a key reason that charter school enrollment has increased to more than 15,000 students — 50 percent higher than four years ago.

In northern New Castle County, where the vast majority of charter schools are located, about one in six K-12 students now attend a charter.

Bancroft principal Butch Ingram echoed Massett when explaining why his enrollment is so low.

“I think it’s just choice in general,’’ Ingram said after Carney, Gregg and other state officials toured his school. “I don’t know if it’s more attractive one way or the other but when parents are provided choice they make choices based on what they think is best for their student.”

Similar sentiments were offered by Mike Kempski, a Shue-Medill Middle School teacher and immediate past president of the Christina Education Association.

Kempski said he and colleagues are saddened to see so many students flee, leaving classrooms empty and renovations unaddressed. On the sweltering September day we met with Kempski, the air conditioning in his classroom wasn’t working.

“There’s families that think they can get their needs for their students met at different places,” Kempski said.

So teaching jobs evaporate, as do the extra academic positions that come with a robust enrollment, he said. “You contract and seem to be on this downward spiral of contracting instead of expanding programs and attracting more people to come in,” Kempski said.

Thousands of Christina kids ‘choice’ into other districts

Beyond the flight to charter schools, about 1,800 Christina residents attend New Castle County’s four vocational-technical schools – Howard, Delcastle, Hodgson and St. George’s. That number has been slowly rising.

Another 1,400 have “choiced” out of Christina to other schools in other districts, such as Red Clay’s Wilmington Charter, Cab Calloway School of the Arts, A.I. du Pont high and middle schools, Delaware Military Academy and Conrad Schools of Science.

That trend is also steadily rising.

Red Clay superintendent Merv Daughtery, whose district has surpassed Christina for the most students in Delaware, said his district has diversified by offering four charter or magnet schools to augments its three traditional schools.

“Perception is always a key in our business – education,” Daugherty said. “I think one thing we’ve been able to do with seven high schools, which are all themed, gives our residents a great option to what’s best for their daughter or son.”

Added Daugherty: “We’ve been able to capture the market of what children need.”

Lack of discipline, failure to embrace charter movement cited

But what is it about Christina schools that have led so many to go elsewhere?

Tara Ann Williams, whose daughter graduated from Christiana High last year after transferring from Glasgow, said dissatisfaction with the district led her to send her youngest daughter to the Friere charter school in Wilmington, about 15 miles from her home.

“As a parent, my perception is that there is a lack of discipline within the schools with some of the kids,’’ she said. “And it causes the kids who are really there for their education to take a step back and not really get involved.”

Last year Williams took her youngest daughter, who was about to enter eighth grade, to charter school open houses. She liked a handful, but some had long waiting lists.

“When I took her to Freire it was a smaller school,’’ Williams recalled. “She was a little concerned about that but a lot of the faculty was there during the open house and she got to speak with them directly about her concerns. And I got to speak to them directly about my concerns as a parent.

“We liked their answers and last year she excelled. She made honor roll all four marking periods. She was captain of her cheerleading team. She is very college driven and she thinks they are going to help her achieve her goal.”

Williams also likes Freire’s discipline policy.

“They have a zero tolerance for violence. There is none. If you are in a fight you are gone,” she said. “They let the children work out their issues by themselves.”

Her message to Christina: “If they actually could make a difference in the middle schools, less parents would leave.’’

Another reason cited by board members is that Christina, which has had several superintendents and acting superintendents in recent years, was slow to innovate and like Red Clay, embrace the charter school movement that has swept across Delaware in the last three decades.

“I think Christina, starting in the mid-2000s we unfortunately had a run of superintendents who were disconnected,’’ Young said. “That discontinuous leadership really contributed to us not having a consistent message or the ability to act as nimbly as needed to what other districts did.”

Paige agreed. “Hindsight is 20/20 and I would agree that we did not embrace the charter movement early enough to really participate fully the way Red Clay has,’’ she said.

Paige said the board has publicly affirmed its belief in charter schools but conceded: “We might just be a little bit late to the game.”

‘We have to be stewards of taxpayer dollars’

When considering whether to close schools, Young and others are cognizant that taxpayers are footing the bill to maintain half-empty schools.

State dollars pay roughly 70 percent of education costs, with local districts paying about 30 percent.

“We have to be effective and efficient stewards of taxpayer dollars. That is what we were elected to do,’’ Young said. “Doing a capacity analysis is the first step in being able to make decisions that are informed and not just decisions based on a momentary trend.”

Massett said the pocketbooks of taxpayers should be considered when officials face the fact that schools are far below capacity.

“If they are that under capacity and they are losing students in their schools, they should consider closing one of those schools because it just makes sense for efficiency’s sake,’’ she said. “It’s not my decision but if I was a taxpayer in that district, I would want to see that.”

Young is hoping the new superintendent and the board can devise winning strategies to attract more students back to Christina.

Bancroft’s Ingram is optimistic about its fledgling Montessori program but that’s competing with a thriving charter Montessori school just a few blocks away.

Christiana High has started a middle school academy in its building, Kempski said that has already drawn students from Shue-Medill, which is only about 60 percent full.

Kempski and others wonder whether it’s time to start an arts academy in the district, a la Red Clay’s Cab Calloway.

“We’re trying to put programs in place to attract students so we don’t have excess capacity,” Paige said.

Should that fail, Paige and others said, uncomfortable conversations might be looming about the fate of schools with proud legacies.

Former Gov. Jack Markell, for example, was known to pronounce that he is a graduate of Newark High, which also has a long tradition of educating the children of University of Delaware faculty.

“If you try to close Glasgow, I’m an alumni of Glasgow. I’d be very upset,” Paige said. “My husband who went to Christiana would not want his building sold or razed.

“My daughter went to Newark. There’s people who say you can’t close Newark. It’s Newark.

“I’m glad there’s that amount of pride. To know it’s going to be a battle, that’s a good problem to have.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.