Luis Echeverria, Mexico leader blamed for massacres, dies

Current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador confirmed the death Saturday.

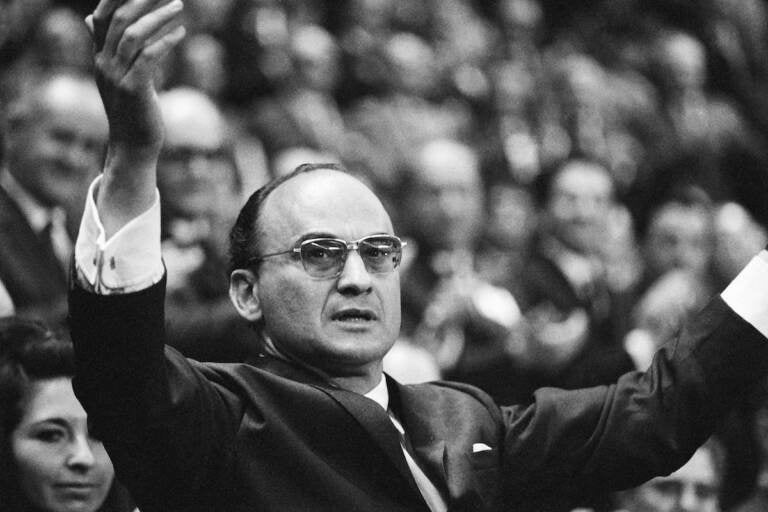

File photo: Luis Echeverria Alvarez speaks to party members after becoming the official nominee for the 1970-76 presidential race, during the closing session of the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party's conventional at the Olympic Sports Palace in Mexico City, Nov. 16, 1969. Current President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador confirmed the death of Echeverria on Saturday, July 9, 2022. Echeverria, who governed from 1970 to 1976, was 100. (AP Photo)

Former Mexican President Luis Echeverria, blamed for some of Mexico’s worst political killings of the 20th century, has died at the age of 100, current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador confirmed Saturday.

In his Twitter account, López Obrador sent condolences to Echeverria’s family and friends “in the name of the government of Mexico,” but did not express any personal sadness about the death. López Obrador did not provide a cause of death for Echeverria, who governed Mexico from 1970 to 1976.

Echeverria had been hospitalized for pulmonary problems in 2018.

In 2005, a judge ruled Echeverria could not be tried on genocide charges stemming from a 1971 student massacre depicted in the Oscar-winning movie “Roma.”

The judge ruled that Echeverria may have been responsible for homicide, but could not be tried because the statute of limitations for that crime expired in 1985.

In 1971, students set out from a teacher’s college just west of the city center for one of the first large-scale protests since hundreds of demonstrators were killed in a far larger massacre in 1968. They didn’t get more than a few blocks before they were set upon by plainclothes thugs.

The main female characters in “Roma” are depicted as incidental witnesses to the slaughter when they go to buy baby furniture at a store near the scene. Unwittingly they run across the protagonist’s sometime boyfriend, who is depicted as participating in the repression.

“Roma” won the Oscar for best foreign language film.

Echeverria had battled respiratory and neurological difficulties in recent years.

In 2004, he became the first former Mexican head of state formally accused of criminal wrongdoing. Prosecutors linked Echeverria to the country’s so-called “dirty war” in which hundreds of leftist activists and members of fringe guerrilla groups were imprisoned, killed, or simply disappeared without a trace.

A motion filed by special prosecutor Ignacio Carrillo asked a judge to issue an arrest warrant against Echeverria on genocide charges in the two student massacres: first for the 1968 killings at the Tlatelolco plaza, when Echeverria was interior secretary.

On Oct. 2 1968, a few weeks before the Summer Olympics in Mexico City, government sharpshooters opened fire on student protesters in the Tlatelolco plaza, and soldiers posted there opened fire. Estimates of the dead have ranged from 25 to more than 300. Echeverria had denied any participation in the attacks.

According to military reports, at least 360 government snipers were placed on buildings surrounding the protesters.

In March 2009, a federal court in Mexico upheld a lower court’s ruling that Echeverria did not have to face genocide charges for his alleged involvement in the 1968 student massacre, and ordered his absolute freedom.

While few people in Mexico mourned the passing of Echeverria, Félix Hernández Gamundi — a 1968 student movement leader who was in Tlatelolco plaza on the day of the massacre, and who saw his friends gunned down — mourned what might have been.

“The death of ex-president Luis Echeverría is regrettable, becuse it occurred in total silence, because despite his his very long life, Luis Echeverria never decided to come clean about his actions,” Hernández Gamundi said.

“Of course we don’t mourn his death,” he said. “We mourn the opacity he displayed his entire life and his decision never to make an accounting, to always take advantage of his immense political and economic power that he enjoyed for the rest of his life.”

.”He delayed for a long time the inevitable process of democracy that began in 1968,” Hernández Gamundi said. “October 2 marked the beginning of the end of the old regime, but it took many years afterward.”

Echeverria’s death came as his Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI — which ruled Mexico with an iron hand for seven decades, before losing power for the first time in the elections of 2000 — is losing what little power it still had, discredited and riven by internal scandals and disputes.

Born on Jan. 17, 1922, in Mexico City, Echeverria received a law degree from Mexico’s Autonomous National University in 1945.

Shortly afterward, he began his political career with PRI. He later held posts in the navy and Education Department, advanced to chief administrative officer of the PRI and organized the presidential campaign of Adolfo Lopez Mateos, who served as Mexico’s leader from 1958-64.

In 1964, under then-President Gustavo Diaz Ordaz, Echeverria was rewarded with the position of interior secretary, overseeing domestic security. He held that position in 1968, when the government cracked down on student pro-democracy protests, apparently worried they would embarrass Mexico as the host of the Olympics that year.

Echeverria left the interior post in November 1969, when he became the PRI’s presidential candidate.

He won that race, and was sworn in on Dec. 1, 1970, supporting the regimes of Cuba’s Fidel Castro and leftist Salvador Allende in Chile.

After Allende was assassinated in 1973 during a bloody coup led by Gen. Augusto Pinochet, Echeverria opened Mexico’s borders to Chileans fleeing Pinochet’s dictatorship.

Echeverria traveled the world promoting himself as a leader and friend of leftist governments. But within Mexico, he was developing a reputation for cracking down on dissent and guerrilla groups.

According to Carrillo, the prosecutor who tried to charge him, Echeverria “was the master of illusion, the magician of deceit.”

Juan Velásquez, the lawyer who defended Echeverria, said the ex-president died at one of his homes, but did not specify a cause.

“I told Luis that even though nobody — not him, not me, not his family — wanted him to go on trial, in the end it was the best thing that could have happened,” because the charges were dropped, Velásquez said.

In his later years, Echeverria tried to project himself as an elder statesman, and a few times— when his health permitted — held forth unrepentantly before journalists. But he mainly lived in reclusive retirement at his sprawling home in an upscale Mexico City neighborhood.

Mexican prosecutors allege that Echeverria ordered an elite force of plain-clothes state fighters known as the “Halcones,” or “Falcons,” to attack suspected government enemies. It was that group that participated in the beating or shooting deaths of 12 people during the student demonstration on June 10, 1971.

Despite decades of calls by activists and opposition politicians for justice, Echeverria never spent a day in jail, though he was briefly declared under a form of house arrest.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.