Learning from McGillin’s: Pedestrianizing alleys means taming trash

Earlier this month we told you about a neighborhood campaign to turn the 2000 block of Moravian Street next to Shake Shack into Philadelphia’s first “green” alley and set an example for other alley transformation projects in Center City.

The trouble with using that project as a model though is that it shies away from taking on the main force for decrepitude on Philly’s alleyways: commercial trash.

The primary reason why Philly doesn’t have great pedestrianized alleys is that the city lets businesses use them as free dumpster storage. Changing alleys requires tackling dumpsters. And if you want to understand how to start clearing out the dumpsters, you have to understand what’s been happening at McGillin’s Old Ale House

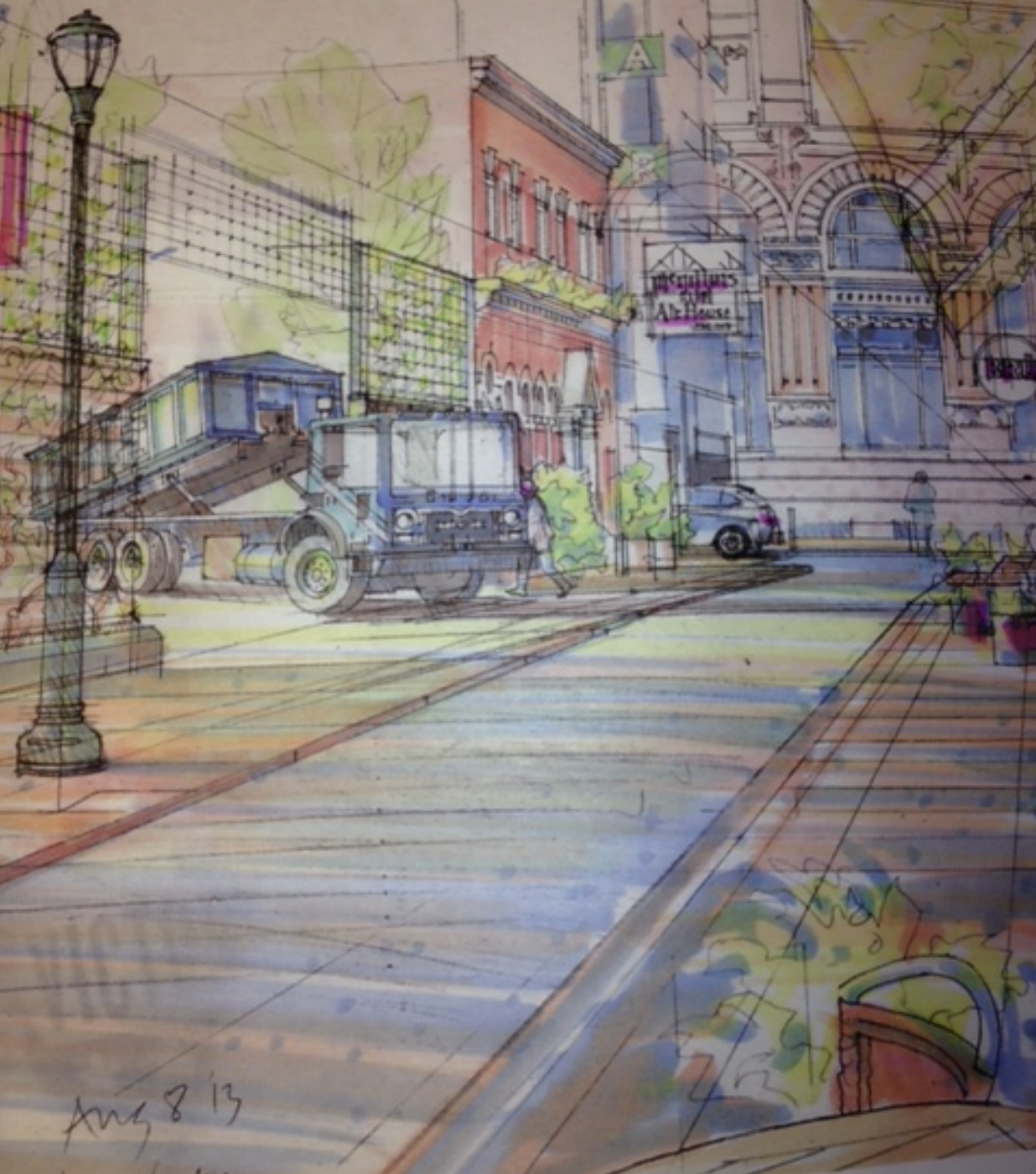

The 1300 block of Drury Street, more than any other block in Center City, is primed for pedestrianization. It’s a short little street that’s already frequently closed down for block parties. It has a famous establishment in McGillin’s, whose owner, Chris Mullins, is a strong supporter of pedestrianization. It also features two other popular bars, Opa’s Drury Beer Garden and Brü Craft & Wurst, that each have back entrances on the alley.

To the east is the highest concentration of outdoor dining and street life on 13th Street, and to the west, the Hale Building’s ornate facade (soon to be restored by Brickstone) creates a particularly striking backdrop for the alley. Brickstone is planning a ground floor restaurant space, and they may be interested in pedestrianizing the stretch of Juniper between Chestnut and Sansom.

These are favorable fundamentals for an alley transformation, yet turning Drury Street into a well-landscaped pedestrian space is still quite complicated. It still needs to function as a service street for the businesses fronting on Chestnut and Sansom. Dumpsters still line much of the block, with garbage trucks rumbling through to empty them at all hours.

“It’s our front door but it’s everybody else’s service corridor,” says Chris Mullins, and even a more spruced up version would still require truck access day and night.

The first point to understand about this issue is that the prospects for cleaning and greening Philly’s alleyways are wholly intertwined with the prospects for reforming the city’s commercial trash policy. And the second point to understand is that Philly doesn’t have a commercial trash policy.

Maurice Sampson, hired as the city’s first recycling coordinator back in the mid-80’s, said Philadelphia had something like 50 waste haulers when he first took the job, most of whom were tiny father and son operations.

“It’s never been regulated,” he said, “It’s a completely independent industry, and the city has done its best to stay out of the way of private haulers. So what you see in the city is the result of just completely ad hoc independent businesses. They come in and they provide service to every business on a schedule that’s a deal between every individual retailer and the hauler.”

While there are rules governing the containment of trash in the city code, city government otherwise takes a hands-off approach to the issues of how, when, and by whom commercial trash gets hauled away, entrusting the thousands upon thousands of individual private contracts between businesses and trash haulers to rid the city of its commercial refuse each day. The teeming dumpster alleys throughout Center City are an organic result of this laissez-faire approach.

Mullins became interested in this issue a few years ago as the number of dumpsters on the 1300 block of Drury began to grow in tandem with the revitalization of the 13th Street corridor, beating a path straight to McGillin’s front door.

“As the neighborhood got better, there was no place for anybody to put their trash,” he said, “and Drury Street became the de facto dumpster street. As bad as it looks today, 2-3 years ago it was 10 times worse.”

Mullins decided to take charge of the situation, reaching out to McGillin’s neighbors, Councilman Mark Squilla, and Center City District (CCD) with a proposal to turn Drury Street into a more inviting public space. As it turned out, Center City District saw an opportunity in Mullins’ plight. Repurposing Center City alleys as usable public spaces had long been a pet interest of CEO Paul Levy and then-Vice President of Planning Nancy Goldenberg, and CCD dispatched Goldenberg to help coordinate an alley demonstration project.

The team retained Maurice Sampson’s firm Niche Recycling as a consultant to create a plan for a “zero waste zone” for the area bordered by Juniper, 13th, Chestnut, and Sansom. They secured a grant from PennFuture to produce some architectural renderings of the concept, and they assembled a powerful team of stakeholders who conceptually bought in to the project, including Goldman Properties, Midtown Village Merchants Association, Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, Washington Square West Civic Association, and most of the businesses on the surrounding blocks.

The logistics of zero waste zones are complex, but the concept is simple enough. If you can reduce the total volume of landfill waste, then you can consolidate the number of dumpsters. That, in turn, allows you to reduce the frequency of trash pick-ups, and ultimately deprioritize dumpsters and trash trucks in the allocation of space on the alleys.

Sampson implemented just such a plan back in 2004, near the White Dog Cafe on the 3400 block of Sansom Street on Penn’s campus. Working with Jones, Lang, LaSalle (JLL), which manages the five commercial districts on Penn’s campus, he created a common area for restaurants’ composting, recycling, and trash needs, radically reducing their landfill waste and dumpster footprint.

On Drury Street, Sampson’s goal was the same: siphon off enough compost and recycling waste that the amount of actual garbage headed for the landfill would shrink to around 10% of the total—the standard for a true zero waste zone, he says.

That may sound impossibly ambitious, but Mullins set out to convince McGillin’s neighbors that it wouldn’t be such a hassle by implementing the plan at his business first to set an example.

“We’ve been doing this successfully at McGillin’s,” he said, ”About 9% of our waste goes to a landfill. The majority of our refuse is compost, and the balance is recycling. It is unbelievable. We’re just a bar—a high volume bar, but if we can do it, the leaders of the restaurant community in our city can also do it.”

That isn’t to suggest the changes were effortless. Mullins says it has taken lots of ongoing staff training and changes in purchasing and other business practices to get the bar’s landfill waste under the 10% threshold.

“Since we are a bar, we use a lot of straws, but now we use corn-based straws that are compostable,” he said, “For high-volume days where we would use the polystyrene cups, we now have compostable cups.”

This hasn’t eliminated the use of trash cans or dumpsters on Drury Street, which was the ultimate plan, but with enough businesses participating, it’s possible to imagine the combined effort making a dent in the dumpster presence.

The team envisioned the empty lot in front of Opa’s Drury Beer Garden becoming a central processing space where the remaining trash storage could be moved off the street. So far though, the lot’s owner has yet to embrace this vision for his property.

Still more obstacles remain: namely funding, settling on a coordinating organization to receive the money, and the costs and logistics of compost pick-up. Getting the zone up and running would require an estimated $150-200,000 in start-up costs. Securing broad buy-in for the plan from McGillin’s neighbors could theoretically bring those costs down, Mullins said, but with no funding stream identified, it’s been hard to lock down any firm commitments.

The team had multiple meetings with Deputy Mayor Alan Greenberger and Councilman Mark Squilla about potential funding sources, but the effort lost momentum about a year ago and hasn’t recovered.

When I spoke with Center City District CEO Paul Levy about the project, he was still enthusiastic about the concept, but was careful to stress just how complicated this all is.

Levy explained that while shared trash storage solutions may sound like a simple fix, the logistics are complex, and the politics are treacherous.

“You have multiple private trash haulers making individual business arrangements with multiple property owners and retailers,” he explained “There are existing business relationships in place, and each business likes to have their dumpster right outside their back door. And this would require a consolidation of dumpsters on the street, and a different business structure—zoned hauling— which several cities have moved to, where the city contracts with different commercial trash haulers to operate in different zones of the downtown.”

Center City District’s recent quarterly digest included an article outlining some advantages of the zoned hauling approach. Levy said he could see some businesses and property owners pushing back on the idea of city government superseding their individual contracts, but he thinks the public interest arguments outweigh these complaints.

“The other side is that consolidation and simplification could free up lots of space,” he said, “Not every alleyway, but a significant number of alleyways could be reclaimed. And the upside is not only vitality and great little streets, but actually increasing tax revenues because the value of real estate and business activity would go up.”

Levy pointed out that the cities who have successfully implemented a zoned hauling policy have tended to be newer cities. CCD’s newsletter mentions San Francisco, Seattle, and Los Angeles as examples of places where this type of policy is working. Still, he doesn’t think the logistical challenges of doing this in an older city with narrower streets present as large of a hurdle as the politics of dumpster sharing.

Businesses who lease space in malls are used to working with a single trash hauler, he noted. At suburban malls, as well as at The Gallery and Liberty Place, “every retailer doesn’t get their own dumpster” he said. There’s a shared dumpster with a key system, where each time a retailer opens it, they’re charged for it. In this analogy, the city, or a smaller public organization like a BID plays the coordinating role of the mall owner.

One of Levy’s ideas for mimicking the mall system in the city was to develop some solar-powered trash compactors that could serve multiple businesses.

“When we first met the BigBelly folks, before they had deployed their solar-powered trash cans, they were working on a solar powered trash compactor,” Levy said, “And we were really interested in a solar powered compactor because it could consolidate dumpsters in the alleyways.”

BigBelly ultimately decided not to go forward with the solar compactors and focused on street trash cans instead.

So what’s next for the Drury Street plan?

Sampson sees an opportunity to reinvigorate public discussion about the project, as well as the broader goal of shrinking the footprint of dumpsters on the public alleyways, when the Streets Department’s Solid Waste and Recycling Advisory Committee (SWRAC) recommendations are released.

The SWRAC is charged with delivering on a 2007-vintage campaign promise from Michael Nutter to create a real waste management policy in the city, and as the Nutter administration draws to a close, the group is just now putting the finishing touches on a 10-year plan, due to be released later this fall.

“The city is now starting to seriously talk about commercial rules and regulations,” said Sampson, “And they’re not necessarily doing that in a comprehensive fashion because they’re fearful of getting in the way and interfering with business. But it really needs to be something we look at comprehensively, because right now it’s horrible. The commercial trash needs to be collected the same way they collect yours and my trash at home. That means having a business association contracting with one hauler to collect all the trash at once.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.