Elaine Kurtz retrospective at Woodmere

Philadelphia-born artist Elaine Kurtz had a unique perspective on souvenirs. Most of us snap pictures or head to the gift shop. But when she vacationed, she had to get her hands on things that many of us overlook.

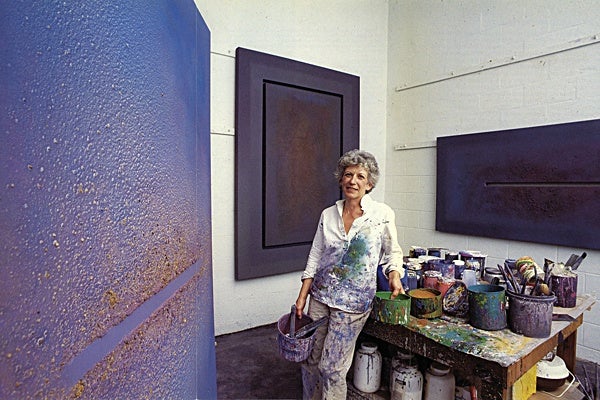

“When we traveled, she was always eager to get to wherever the beach was to see what the sand was like,” husband Jerome Kurtz remembers in the interview featured in the Woodmere Art Museum’s catalogue of their new exhibition. Force of Nature, the first-ever retrospective of Kurtz’s work, opens on Friday.

When she ran to the beach in Tahiti, she discovered an expanse of course black sand.

“Oh my god. I’ve got to get some of that,” she said. She took a fifty-pound box of the sand to the post office.

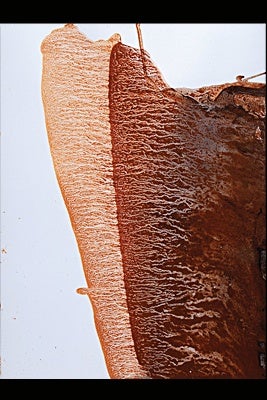

The rich, red mud of an Alabama trip had a similar effect, as did troves of mica, New Jersey sand, small stones, copper, obsidian and other volcanic rocks. These materials and more would meld with traditional media on her canvases to create images that are sculptures as much as they are paintings.

Born Elaine Kahn in 1928, Kurtz graduated from what is now the University of the Arts in 1949, and married Jerome Kurtz in 1956. In the 1970’s and 80’s, New York City and Philadelphia were rife with her solo exhibitions.

Woodmere Director and CEO William Valerio calls the current retrospective “a powerful body of work”, and though few people are familiar with Kurtz today outside of well-cultured art circles, he called her “a leading force in the arts in Philadelphia” during her heyday.

Kurtz’s paintings

The main part of the exhibition, drenched in natural light in Woodmere’s lofty, two-tiered main gallery, takes a reverse chronological approach to Kurtz’s work. The viewer first encounters the artist’s late-life stylings, dubbed the Alluvial paintings.

To Valerio, these paintings evoke the way “movement of water shapes the earth.”

Many paintings in the collection were leant or donated by local owners, and others already resided in Woodmere’s archives. Especially in an era where we’re usually content to gaze at screens and photographs, no two-dimensional reproduction could do these paintings justice: they demand to be seen in person.

At first glance, 1990’s Alluvial Series IV, incorporating sand, pebbles, mica and acrylic on a 23×84 inch canvas, is a gentle exploration of evening-sky colors over the smoothness of an implied dark-blue horizon. But a closer look reveals the subtle complexities of Kurtz’s work, and movement swells from her masterfully balanced modulations of color. Sandy swaths cover the painting’s upper half, enticing us with the paradox of evoking the stars with pieces of earth while also subverting our natural urge to perceive a literal landscape.

Other Alluvials are like birds’-eye views of fantastical yet gritty geographical surfaces. Strangely familiar shapes and textures kiss, diverge and collide to evoke graceful deltas, verdant fjords, scurrying gravity-sculpted rivulets and stark moonscapes.

Look carefully at one painting that features a bold slash of that Alabama mud: the footprints of Kurtz’s cat, cruising around the studio while her owner worked, are still faintly visible.

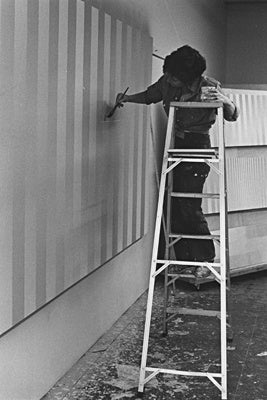

Kurtz’s earlier pieces, unfolding as the exhibition progresses, are a feast of stunning brushwork: deceptively simple paintings of geometric shapes or solid, carefully-toned bars of color demand a second and third look. By the cunning juxtaposition of matte and shiny effects, along with a range of shifting slate-like tones, a large rectangular canvas of five vertical black bars becomes anything but black stripes. Other paintings turn the viewer into a visual detective, discovering whether apparent shifts in color are actually an optical illusion.

The concentric squares of 1976’s “X Extended” seem to swoop and wave as if wriggling to escape the painting’s confines, and the lines of 1972’s “X” and “Blue X” appear to pulse as the eye meets them. Many other paintings from this era demand that viewers shift their position to parse the dizzying engagement of Kurtz’s shifts in tone, color and line.

Valerio particularly enjoys 1974’s “Cool Spectrum,” five feet high and nearly twenty-one feet long, for what he called Kurtz’s ploy to “monumentalize optical effects”. Horizontal bars of color slide from yellow to green to blue to purple, their razor-straight lines seeming to undulate as they glide between subtle shading and regimented collisions.

When asked what someone would do with such a large painting, Kurtz apparently retorted, “What does that have to do with anything?”

Valerio points out the “incredible finesse” of Kurtz’s strokes with the brush: her color gradations are as smooth as a modern digital painting. Earlier work – such as a delicate gray still-life of flowers from 1970 – proves her skill as a draftsman. “If she wanted to draw a vase of flowers, she could,” Valerio said. But she was usually after something far more challenging and enveloping than representational images.

The show also includes Kurtz’s possibly unfinished final work, before her sudden death from a brain aneurism in 2003.

Artists inspired by Kurtz

Kurtz is not the only one currently featured at Woodmere. This exhibition actually has two parts: Force of Nature offers Kurtz’s retrospective, and Elemental: Nature as Language, in line with Woodmere’s mission to showcase contemporary Philadelphians, features the work of other artists whose pieces echo or were inspired by Kurtz.

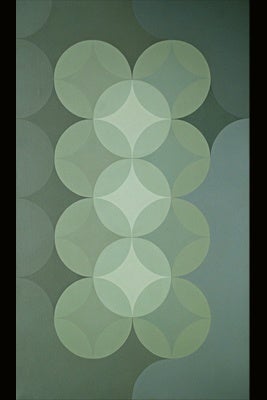

Some pieces by artists such as Edna Andrade come from Kurtz’s friends and contemporaries. In Andrade’s 1969 six-foot-square “Emergence II”, a riot of small, half-white circles seem to cartwheel madly just beyond your pupils’ gaze. Others play on Kurtz’s affinity for surprising complexity of sheen and tone. The youngest artist on display is twenty-five year-old Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts student Samantha Dylan Mitchell.

“We’re committed to really engaging with younger artists in the city,” Valerio said, to display their “energy and fluorescence”. He was drawn to create these partnered exhibits for the potent dialogue they offer between artists of different generations.

“We want to show how issues that mattered to Kurtz still matter to artists living and working in Philadelphia today,” he said.

Woodmere’s Kurtz retrospective, Force of Nature, and Elemental: Nature As Language In The Works Of Philadelphia Artists, run through April 22, with an Open House on Saturday, February 25 from 1-4 p.m.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.