Here we go again: Residential, restaurant, office space proposed for Arch

Talk about moving on.

A couple years ago, the Planning Commission was being wooed by developers who wanted to plop a monolith called the American Commerce Center, a mixed-use tower which would be among a handful of the tallest buildings in the country and a third again the height of the Comcast Center, down on a parking lot at 18th and Arch Streets.

With financing in the tank, that project has sat idle.

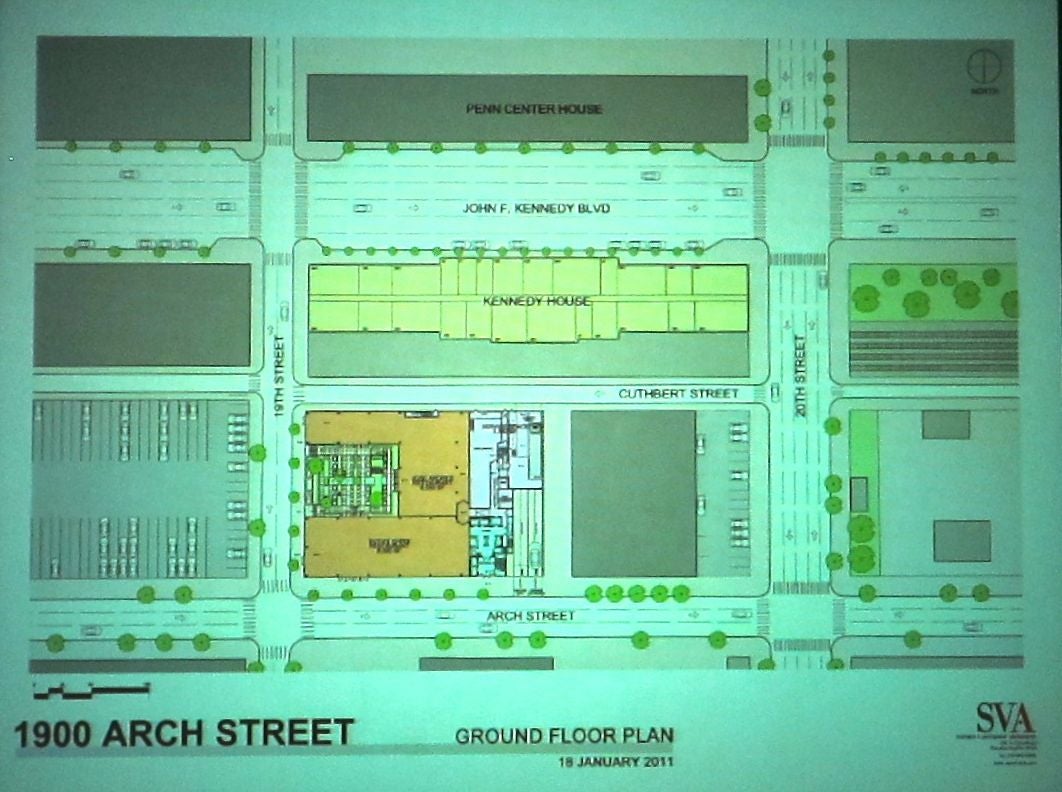

But Tuesday, Philadelphia developer Eric Blumenfeld told the PCPC he wants to bring a three-building complex of 236 apartments, 10,000 square feet of office space and two restaurants to 19th and Arch Streets. Just a block away from the stalled ACC caper.

Blumenfeld, developer of the Marine Club Condominiums in South Philadelphia, told the Philadelphia City Planning Commission Tuesday that “this design is a great building for world-class restaurants.” Blumenfeld, who has worked with Philadelphia restaurateurs Stephen Starr and Marc Vetri, said that both restaurants would be about 800 square feet and would include three walls of windows that would provide connection to both the street and one of two courtyards.

Two-levels of underground parking for 65 cars each would be accessible from Arch Street, but loading for residents and the businesses would be off of Cuthbert Street, at the request of “near neighbors,” he said.

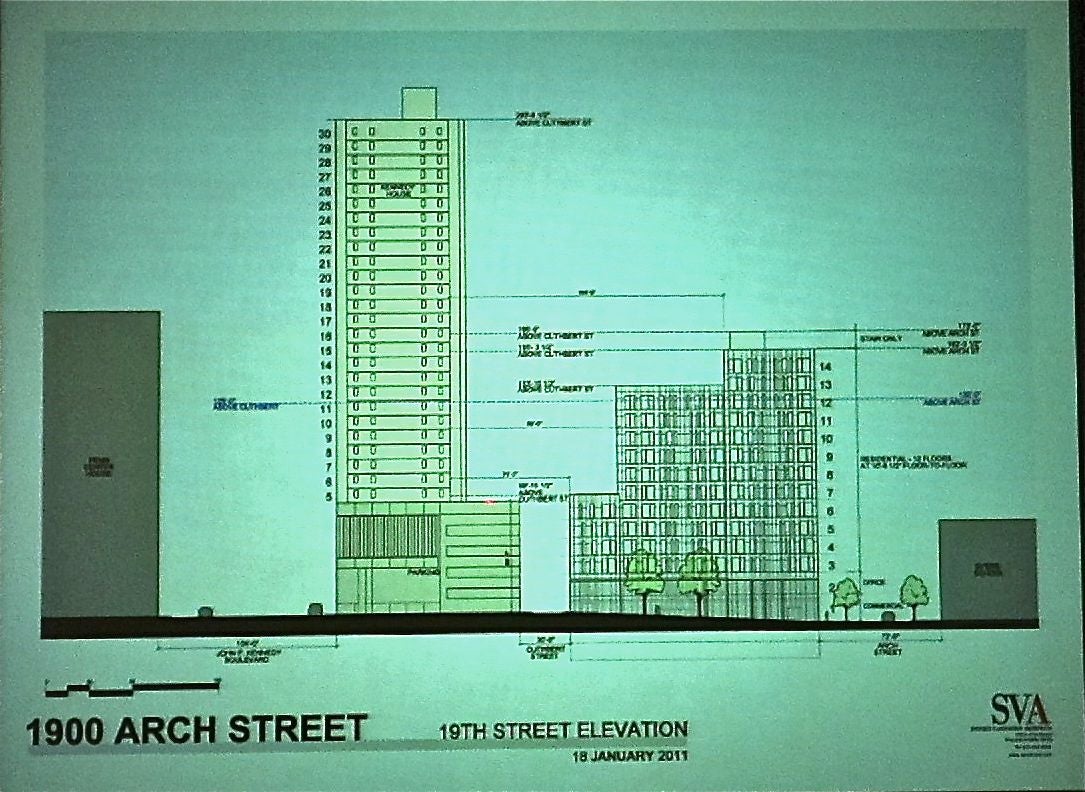

Blumenfeld described the buildings, designed by architect Stephen Varenhorst, as “an integrated series of three buildings,” one six stories tall, one 12 and one 14. “We really tried to design something that was very urbanesque and very livable,” he said.

But to build it, he’ll need variances related to height, density and curb cuts.

The building site is within the Logan Square overlay district, which limits building heights to 125 feet. But Varenhorst and Blumenfeld told the planning commission that the complex is 162 feet at its highest point. The tallest building looks like three tiers, stepping toward Arch Street and away from the Kennedy House apartments so that the shortest “step” is closest to the apartments and the tallest part of the building is the furthest away. This was done intentionally to preserve the views and light for Kennedy residents, Varenhorst said, and it is this massing strategy that pushed the building beyond the height limit, he said. That’s variance number one.

The two lower roofs will be green roofs, Varenhorst said, so the Kennedy residents have something natural to look at.

It was also at the request of neighbors, Blumenfeld said, the entrance to the two floors of underground parking is located on Arch Street. This, too, requires a variance.

But what Deputy Mayor and Planning Commission Chairman Alan Greenberger sees as the biggest hurdle for the developer is the proposed density of the plan. The property is currently zoned C-4. This allows for a floor-to-area ratio of 5. (This means that a building that took up the entire property could be five stories tall.) The proposal is coming in with a floor-to-area ratio of 7.7. In other words, it’s more dense than is allowed.

Under the current zoning code, developers who set aside 30 percent of their property as public space get a significant density allowance. For this parcel, instead of being limited to a ratio of 5, the developer could have a ratio of 13. Blumenfeld said he hoped the two courtyards in his plans – one of 5,200 square feet, and one of 4,800 square feet – would fulfill that requirement.

But Greenberger predicted he would have a hard time convincing the Zoning Board of Adjustment to grant this relief, considering that access to the smaller courtyard would be limited to building residents and office workers. “One is public, one is not,” he said.

The larger courtyard might not be considered a totally public space, commissioners said, since part of it would provide outdoor seating for the two restaurants in warm weather. In answer to Commissioner Nancy Rogo Trainer’s question on this issue, Blumenfeld said the restaurants would have some say in how much of the outdoor space they wanted to use, but he would hope it would be about 1,000 square feet.

Syrnick and Greenberger told the developer to think long and hard about the public space component. Once density relief is granted, it has to stay public forever, they warned – there would be no gating it if, for example, residents were to complain about noise.

The developer said these issues have been discussed with neighbors already.

Blumenfeld said he hoped construction would start this spring. He does not yet have financing.

Greenberger suggested that if it turns out construction won’t start until later, Blumenfeld might want to consider waiting for the adoption of the new zoning code. The proposed new code changes the “all or nothing” public space for density swap to a pro-rated system, Greenberger said, so the public courtyard would get some density relief for the project. The new code also contains other density incentives for gold or platinum LEED certification, public art and underground parking, among other things. Underground parking is proposed for this project.

The presentation was for information only – the developer will be back before the planning commission requesting its approval in the future. Greenberger suggested that Blumenfeld first bring an analysis of how the increased density for public space swap would work out both under the old and proposed codes to planning staff.

After the meeting, Greenberger said the hope is that the new zoning code is presented to City Council in February and that they adopt it by June. The Planning Commission will recommend it not be fully in effect for six months after that, he said. But during those six months, it is likely that Blumenfeld – and all developers – will be given a choice of which code they would like to follow – old or new.

This step is commonly taken when such a big change is made, Greenberger said, and it would give staff in the various city departments that must work with zoning a chance to get used to the new regulations. Developers should know, however, that they must pick one code or the other – they can’t pick and chose the regulations they like from both, he said.

Back when the talk on Arch Street was the American Commerce Center, one big change was the knock-down of two 1850s buildings at 1900 and 1902 Arch that were the long-time home of Fernley & Fernley, a company that manages non-profits and professional organizations. Fans of the buildings tried to save them, but in the end, the Historical Commission decided it was OK to demolish them, and they were replaced with a parking lot.

In other planning commission business, new commissioner Beth Miller, who is executive director of the Community Design Collaborative, was sworn in. “It’s quite an honor and I hope to be worthy of it,” she said.

Jastrzab gave the group an update on the Philadelphia2035 – the city’s in-the-works comprehensive plan. “Staff is working furiously trying to finalize” the draft, which he anticipates will be presented to the commission at its Feb. 15 meeting, and also posted on the planning commission’s website.

Six weeks of public review and comment will follow. In March, a separate 2035 website will launch, he said. Toward the end of March, a special public meeting will be held to take input on the city-wide master plan and to launch the first of the district plans, Jastrzab said. The final version of the Master Plan will be presented in May, with hope that the commission will adopt it at its May 17 meeting, he said.

Commissioners also accepted the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation’s “Industrial Land & Market Strategy for the City of Philadelphia” – a report of land use recommendations which senior vice president John Grady said was a joint effort with the city’s planning and commerce departments. The study will be used to guide future land-use decisions, but its guidelines are just that, Greenberger said – the commission has flexibility not to follow them if they don’t fit circumstances. Greenberger said such instances will be rare. The study will help not only with individual projects brought to the commission, but also with the district-level master planning, Jastrzab said.

Grady said that while Philadelphia’s industrial base has shrunk over the past ten years, this is not a post-industrial city. Defining industrial jobs as those entailing production, distribution or repair, 104,300 city jobs – one out of five – are industry-based, he said. These jobs have a combined payroll of $5 billion, and provide the city with $323 million in taxes each year, or about 15 percent of the general fund, Grady said.

The number of jobs have stabilized, Grady said. The study he presented looked at ways to foster growth of the sector by focusing on three categories: Traditional manufacturing of things like food and apparel, advanced manufacturing including medical devices and biopharma and transportation of goods and services. On the last category, Grady noted that Philadelphia is located within a day’s drive of two-thirds of the country’s population, making it a great spot for distribution centers.

The growth goal set in the report is the creation of 22,000 jobs over the next 20 years, which would translate to about $1 billion more in wages and $68 million more in city tax revenues.

To do this, Grady said, the city will need 2,400 acres of “developable industrial land.” No one is recommending taking land used for other things and making it industrial, he said. Rather, the report calls for the redevelopment of land that is already zoned industrial but is either not being used or is underutilized.

Modern industry requires a new way of thinking about industrial property, Grady said. The biggest change is that rather than putting up a building tightly tailored to a specific industry, the city should focus on flexible space that can be easily adapted to many different purposes.

Most of the land the study identified as being ripe for new industrial growth is in South West Philadelphia along the lower Schuylkill and in the North East, with some also located along the north and north-central portions of the Delaware River, he said. Those working on the Master Plan for the Central Delaware have also identified those same parcels for light industry. Community organizations in the area are open to some industries, but not others, and are currently working to define what is and what is not acceptable to them, through the Central Delaware Advocacy Group.

Another key component of the study focuses on the work of the Zoning Code Commission. It recommends that the number of industrial zones defined in Philadelphia shrink from nine to five. Currently, about 80 percent of the industrial parcels in the city are either G2 – general industrial – or L2 – limited industrial.

The study recommends boiling those down to heavy industrial, general industrial, light industrial, commercial mixed use industrial and residential mixed use industrial. Heavy and general industrial would be concentrated mostly in the south west, Grady said. Most other places would be light industrial.

The two mixed-use categories would be used for areas in transition from industrial to either commercial or residential, he explained.

Craig Schelter of the Development Workshop – a non-profit representing developers and landowners – asked the commission about the difference between adopting a plan and accepting a plan.

Greenberger said that particularly in areas of transition, there is “probably an open debate about what it will become.” Accepting the recommendations rather than adopting them gives the commission more flexibility to take into account both public desires for a parcel and market forces and the private sector, he said.

As an example, Greenberger spoke of the former Tastykake site in Hunting Park West. The plan says this is an area for further industrial growth, and some transitional development. “The community really wants retail and a supermarket,” he said, and that’s in the works. “But you could probably argue if an industrial use came along that was as compelling, we could have made a case for it.”

Still, Greenberger said, “for a very high percentage of proposals we see, we will generally conform with this.”

Read the executive summary of the recommendations here. Download the full report from the PIDC website here.

The Planning Commission also gave its nod to the 58th Street Greenway, a walking and biking path that will link Cobbs Creek to Bartram’s Gardens. The shared-use path was carved along one side of the roadway and in most places is 10-feet wide and has a 4-foot, 8-inch grass buffer between the pedestrian/bike lane and street parking. About 90 percent of the planning is finished, and the hope is that the Greenway will be built by February 2012. The 58th Street Greenway will be a portion of the East Coast Greenway, which will eventually connect Maine to Florida.

Commissioner Nilda Ruiz had a safety concern. “It looks scary to have walking and bikes all in the same path,” she said.

Spencer Finch, director of sustainable development programs with the Pennsylvania Environmental Council – the agency leading the Greenway planning – said such a plan only worked in this area because the sidewalks were originally 15 feet wide. “To reduce your fears, think about Kelly Drive. It’s the same idea,” he said.

The biggest safety concerns are at intersections and driveways, Finch said. But the route the Greenway route was selected in part because there are so few driveways and doorways. Much of the property that travelers will pass is divided into large parcels, most of which are institutional, he said. They will also pass a city rec center. Ruiz joined the rest of the commission in approving the proposal.

Reach the reporter at kgates@planphilly.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.