Gift to Princeton puts spotlight on rare books housed at the university for decades [photos]

Last week, Paul Needham got a call at 8:30 p.m., from the BBC. It was 1:30 a.m. London time, and a late-night radio show wanted to talk with the librarian at Princeton University about its recently acquired collection of rare books.

“I have no idea who the man was, what the show was called, nor who was awake and listening,” said Needham. “I was speaking into a void. Who knows what happens?”

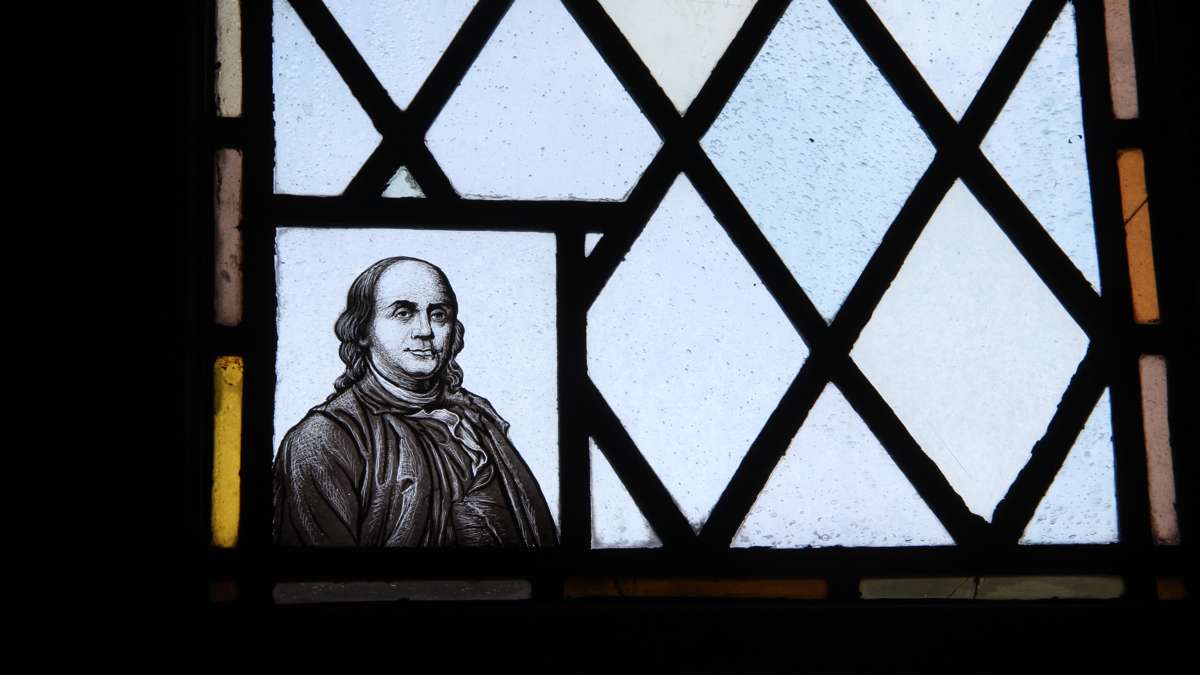

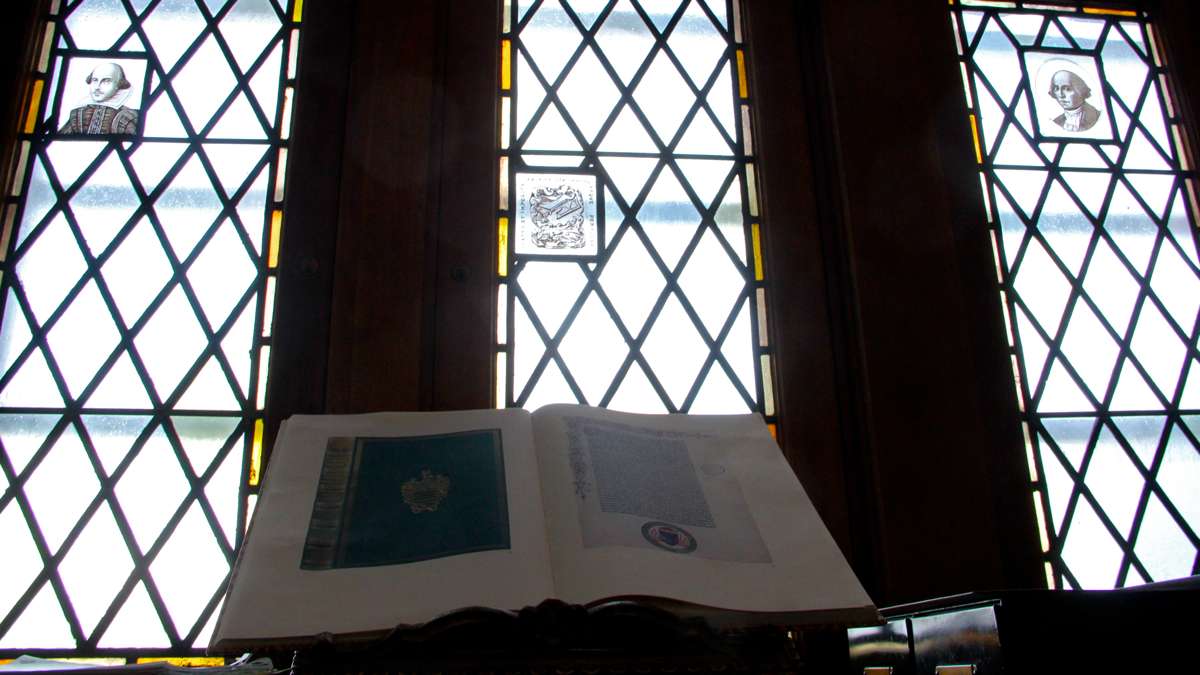

Needham also got a call from NPR’s “All Things Considered,” during normal buisness hours. He has been overseeing the Scheide room at Princeton’s Firestone Library since 1998. The room, which has housed the Scheide collection on campus since 1954, is a re-creation of the family library in Titusville, Pa. It has some of the dark-wood bookcases and oak furniture from the original library built in 1922, as well as the custom-made stained glass windows etched with portraits of people such as William Shakespeare, George Washington, Charles Darwin, and Christopher Columbus — all heroes of the John Scheide, a patriarch of the book collection.

The Scheide collection was slowly and carefully built over three generations. William Taylor Scheide, a self-educated man who made a fortune in the 19th century Pennsylvania oil boom, his son John Scheide who built the library, and then his son, Bill Scheide, who moved the collection to Princeton in 1954 and ultimately bequeathed it to the university upon his death last year at age 100.

“It only has about 2,500 items, but it’s the best library in the world on that scale” said Needham. “In terms of early printing material, it is absolutely one of the handful of great collections in the world.”

The collection is strong in first-edition publications by the early explorers of the New World (an interest of William Taylor), the earliest printed books and broadsides (a passion of John) and original musical manuscripts by Bach and Beethoven (the youngest Scheide, Bill, was a music historian).

“Not a day goes by that I don’t pull a book off the shelves, to learn something,” said Needham.

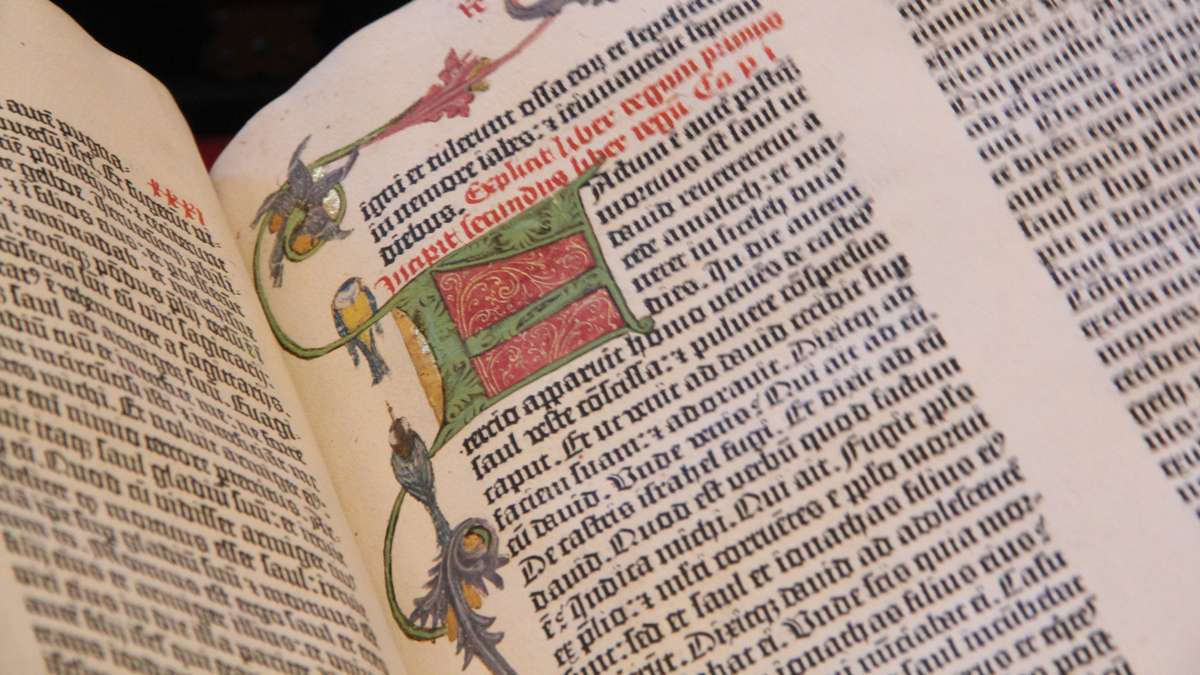

One of the gems of the collection is an original Gutenberg Bible, printed in 1455. If you bought a copy of the first printed bible almost six centuries ago (in German, of course) you would have received a rather plain-looking volume with big spaces left unfinished.

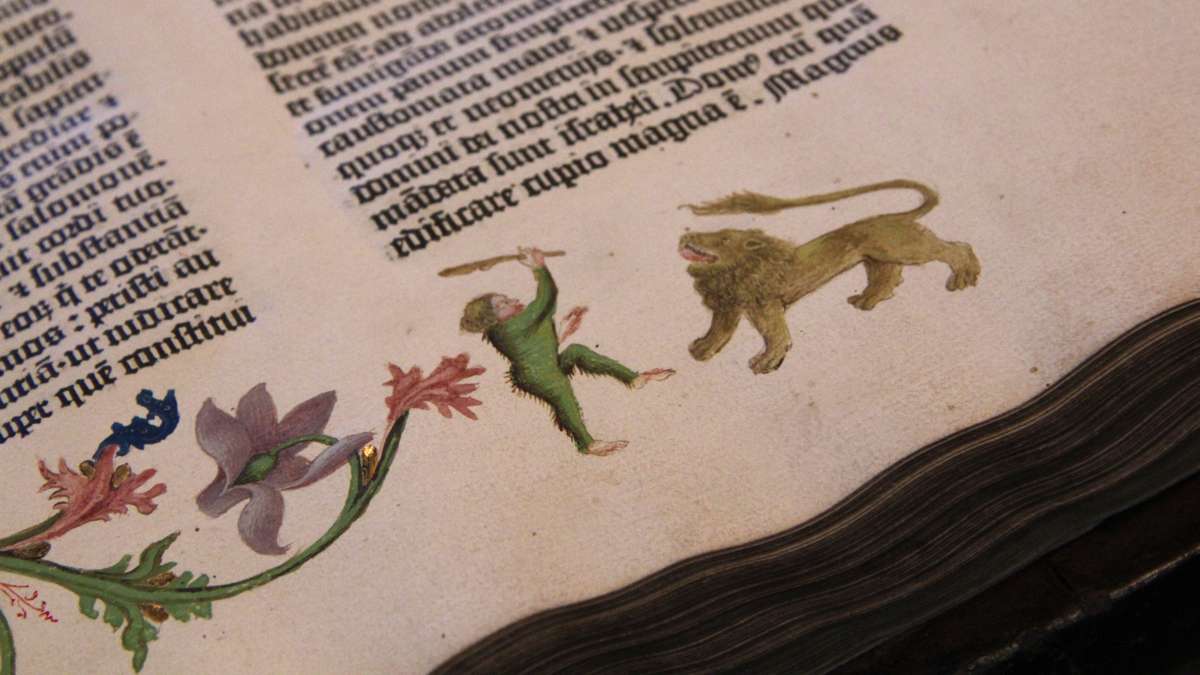

“You had to hire a person called a rubricator, or an illuminator, to fill in all the parts that the printing didn’t give you,” said Needham, flipping through the bible. “They probably paid the illuminator extra for the floral illumination, and to add some animals. Probably charged separately to draw animals.”

Needham stops at a particularly arresting illustration. Among the floral designs along the bottom of a page are two little figures of a lion and a man, which the illuminator would have copied out of his own collection of stock images. They appear to be fighting.

“He had a lion, and a picture of a wild man, a green man — a man of the forest,” said Needham. “So he put the two together, the man and lion, to have a little battle. That’s one of the nicest images.”

Needham then turned to another prize, an original printing of the Declaration of Independence. The printed version actually pre-dates the hand-written version with all the famous signatures.

When the founding fathers of the Continental Congress finally settled on the language they could all agree upon, in Philadelphia in 1776, the first thing they did was send it to a local printer, John Dunlop. He quickly churned out a few hundred copies that were immediately distributed throughout the colonies to inform the new citizens of the United States of America the parameters of their own government.

The display copy, now housed at the National Archives, was made a several weeks later, having spent considerable time circulating among the forefathers to get all those signatures. The printed versions, the ones meant for the people, are the originals.

“About 25 copies survive,” said Needham. “This was the only one in private ownership.”

Not anymore. That copy, and all the rare books of the collection, are officially property of Princeton University as of last Tuesday.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.