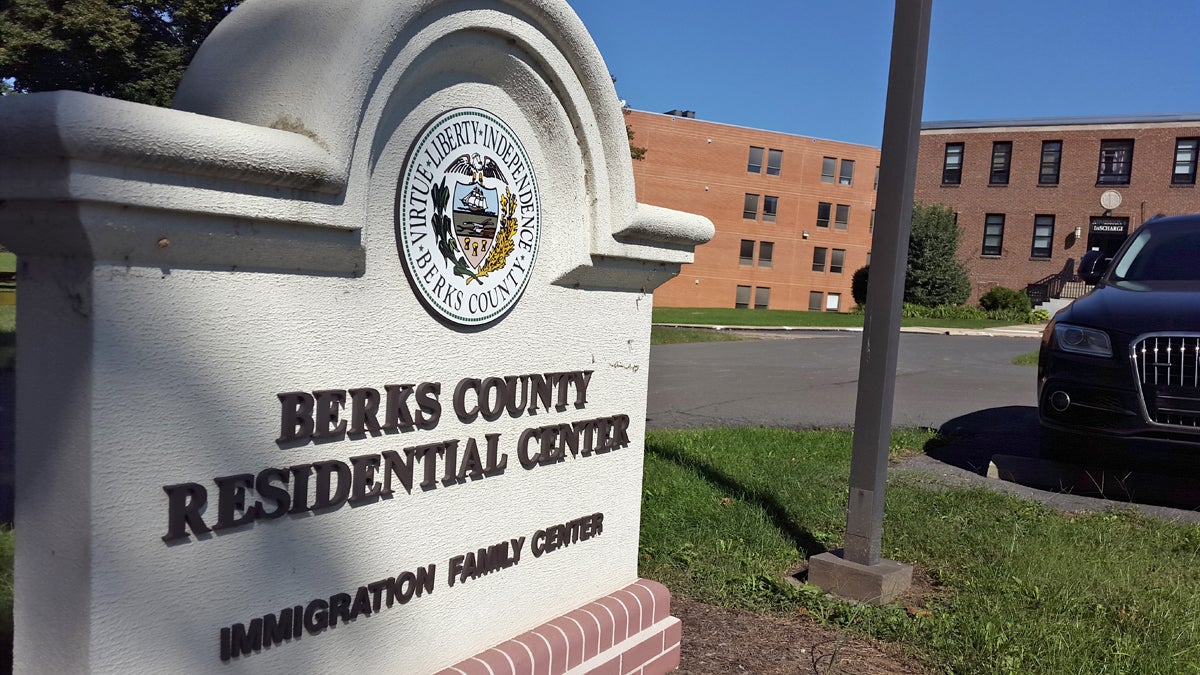

Four families held at Berks detention facility win temporary delay from deportation

Berks County Residential Center. Oct. 6, 2016 (Laura Benshoff/WHYY)

What happens when a child brought into the country illegally earns legal status, but the parent who brought that child hasn’t?

Wednesday, U.S. Judge Lawrence Stengel ruled that the government cannot transfer or deport four Central American women and their children detained in the Berks Family Residential Center while that question is debated.

“It’s similar to the [response to the] Muslim ban, where the courts will stop an action out of an abundance of caution, while it can determine whether there are rights that need to be vindicated,” said attorney Bridget Cambria, who represents the women.

The four children — all between the ages of 3 and 16 — have earned what’s called “Special Immigrant Juvenile Status.” State courts can grant that designation to immigrant children who have been “abused, abandoned or neglected” by at least one parent and who would be endangered in their home counties.

Earlier this week, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a petition on behalf of these and other Central American mothers and children seeking to have their asylum claims heard before a judge. That case had held up other forms of immigration enforcement or relief the families were seeking.

The four mothers of special immigrant juvenile status children, along with 10 others involved in the Supreme Court petition, have been detained at the federal immigrant family detention center in Leesport, Pennsylvania, for more than a year and a half.

Following the court’s rejection, the women’s prospects for remaining in the U.S. dimmed considerably.

“l’m happy because of the visa my son has — but, at the end of the day, there’s nothing for me,” said one of the mothers involved in the case, who spoke under the condition her name not be used. She and her 4-year-old son fled Honduras in 2015. Like the other mothers, she requested asylum in the U.S. based on gang and gender-based violence in her home country.

“But what my son has does give me a little comfort because he’s so small, he has to stay with me,” she said.

Because the intent of the law is to protect children who, according to a court determination, will be harmed in their home countries, Cambria and other attorneys argue they should not be deported.

Immigrations and Customs Enforcement officials declined to comment on pending litigation. In court documents, the government argued that the children are deportable because their applications for permanent residency are still pending, and because their asylum claims were handled through a special, streamlined process called “expedited removal.”

In his order, Stengel forbade the government from transferring or deporting the women and children until a hearing scheduled for May 19.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.