Finding the human heart where art and medicine intersect

For Nazanin Moghbeli, a physician and artist who lived in Iran until she was 9 years old, culture, work and art come together in a way that’s especially grounded in just being human.

A clinical assistant professor in cardiology at Penn Cardiac Care at Radnor, who also has an art exhibit from April 18 to May 13 at the University of Pennsylvania Burrison Gallery, Moghbeli sees both the medicine and the art as manifestations of her own humanity.

“I enjoy taking care of patients and being there for families,” she says, “and I need the art to complement that, to help me find meaning and context, in my efforts to help my patients live longer and healthier.

“There’s beauty in art and a way to reach beyond what we have in the flesh. The creative process allows me access to that. I couldn’t take care of sick patients without having a foot in something beautiful and different from suffering.”

Art and medicine as complements

The art and the medicine fuel each other, and for her the two are not at all hard to reconcile. “I’ve always done both,” Moghbeli says. Her work in the field of medicine keeps her grounded in the body, but in a different way.

“It has to do with the process of people letting me into their lives at a vulnerable time. It’s an honor to be allowed into that. I feel that gratitude for those interactions with patients. They provide a context for the art in my life. There’s something really motivating about the contrast between working with patients, and leaving that setting and going into my studio to make artwork.”

And though the demands of being an artist and physician (and wife and mother of three) can be a challenge, the upside is that it balances the extreme pressure of working in life-and-death situations with working in a realm where performance pressures are very different. “The stakes are so low for me that it’s incredibly freeing,” she says. “No one’s going to die, and it’s going to be fine. I can just engage in the process of creating art. If it turns out to be beautiful, that’s a bonus, but that’s not why I do it. If I were a full-time artist, I would feel more inhibited in my [artistic] work.”

Seeking not ‘art’ but ‘authenticity’

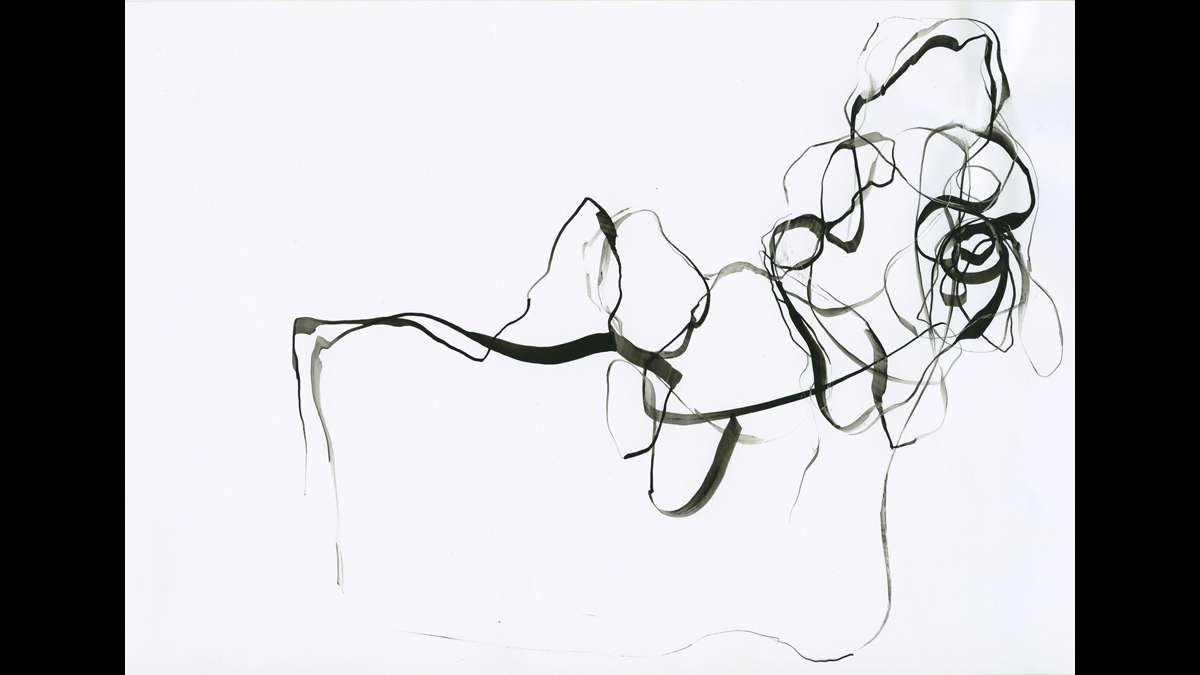

I stopped into the gallery in Old City that recently featured her drawings in an exhibition and was immediately struck by their simplicity and beauty. As I shifted from sketch to sketch, dark calligraphic strokes on white backgrounds, each one gave me a sense of physical motion. Inspired by calligraphy, they felt like a dance of the pen. In short, it felt very human to me.

Moghbeli calls her pieces drawings because, while they do borrow a great deal from calligraphy, they go beyond script to make marks and motions into something more abstract. I asked her about how she achieves that.

“[For this series] I was getting up early in the morning,” she says. “I would meditate, and then I would sit at my desk and draw, like 5 in the morning, almost half-asleep and under-caffeinated. I made the drawings, and it was all about what my hand was doing and not about my brain.”

It sounded like creating these works had been totally about the process. “Yes,” Moghbeli says, “I think making art has to be about the process. You can’t set out to make more great art. You have to make what’s authentic.

“Something that really stuck out for me was that I had been reading a lot about Buddhism and meditation — you just show up, you don’t worry about whether you’re going to do a good job meditating. I decided I’d sit at my desk 45 minutes every morning, and that was enough. It’s not about what I make. I was going to show up and do it.”

An old inflluence comes calling

But something else showed up: the influence of calligraphy in her childhood culture of Iran. “The other thing that was instrumental for me,” she says, “was when I went to Istanbul with my mother, who’s a calligrapher, and my daughter, and we spent a lot of time looking at calligraphy.”

In Muslim cultures, the use of religious imagery is limited, but other beautiful forms of visual art, such as calligraphy and mosaics, have been emphasized and have flourished. Moghbeli agrees: “Historically, you couldn’t pursue the figurative branch of art.”

But her childhood experiences shaped her move toward calligraphy without staying within its confines. “I want my work not to be so literal and not to only evoke those beautiful Islamic texts.”

Now she sees these strands of her work as physician and artist continuing to unfold in new directions. “It was refreshing to be in a Muslim country, in an environment that felt so positive,” she says. “I loved hearing the call to prayer and being in a mosque. The calligraphy and art really clicked for me. It made me want to practice more calligraphy in depth. That experience had a lot to do with the new direction I find myself with art.”—

Come join folks featured in “Human At Work” as well as other fellow Philadelphians to connect our personal work stories with the city’s story. Join us for our first Human At Work event, “City and Self: Bringing Humanity To Work.” It’s free, but registration is required. You can email me in advance with questions; I hope to see you there!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.