FDA approves female libido pill, but includes safety warnings

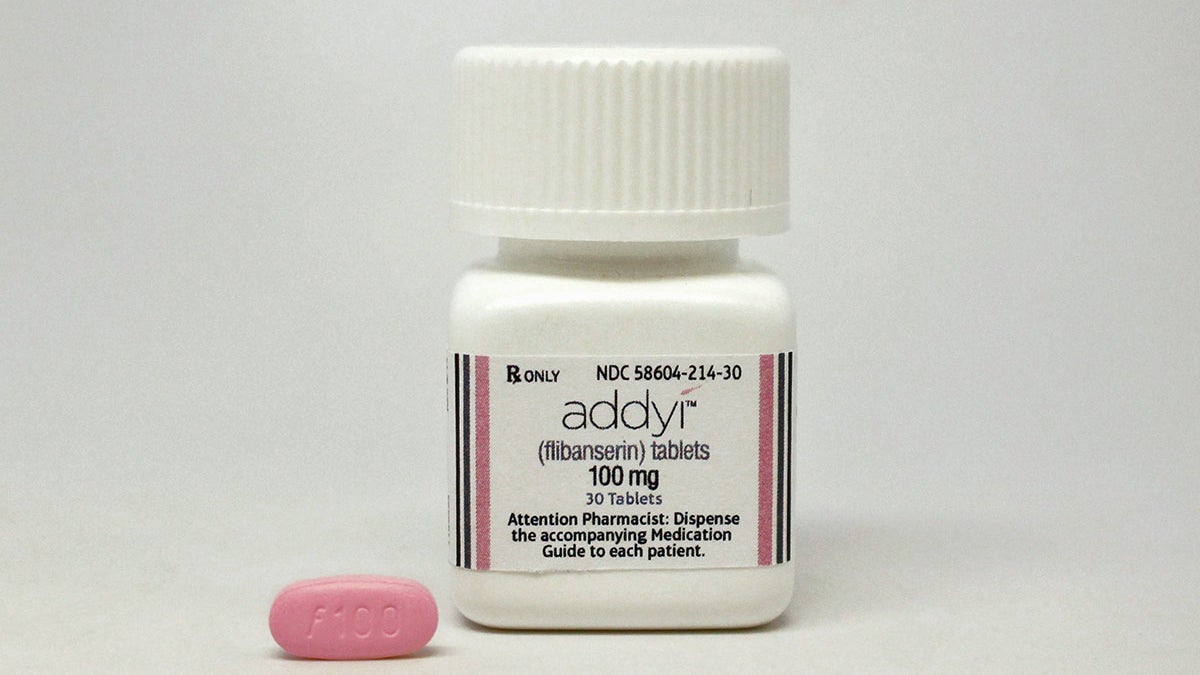

Sprout Pharmaceuticals has received FDA approval for its libido-boosting drug flibanserin, which it will sell under the brand name Addyi. (Image courtesy of Sprout)

There’s now a pill for women with little interest in sex. On Tuesday, the FDA approved the first drug to treat sexual desire disorder. Sprout Pharmaceutical‘s Addyi is specifically for pre-menopausal women, and in recognition of serious side effects, will come with a boxed warning and restrictions on prescribing.

‘A wonderful day’As early as Wednesday morning, Drexel professor and director of the Pelvic and Sexual Health Institute, Kristene Whitmore, said she had a patient inquire about the drug.

“I said, ‘Are you willing to pay $400?’ And she said, ‘I can’t afford that right now.'”

The pill has not yet been evaluated and approved by insurance companies, meaning that for now, patients will have to pay out of pocket.

Whitmore is also taking the safety warnings seriously. Women should not drink alcohol while on the drug because it can lower blood pressure and lead to sudden fainting. To minimize risk, the FDA has also mandated that doctors and pharmacies complete special training before dispensing Addyi.

Given those limits, it remains to be seen how many women will become users of the “little pink pill.” Still, Whitmore is glad to have the option.

“I think it’s a wonderful day that women have a medication for sexual dysfunction,” Whitmore said. “Since 10 percent of women have libido or desire disorder, this is a very nice opportunity for them to get help. That hasn’t been possible in the past.”

A problem with alcoholAddyi’s road to approval has been long. The drug, which also goes by the generic flibanserin, was developed as an antidepressant and acts on serotonin receptors in the brain — one reason the comparison to Viagra is misleading.

In June, University of Pennsylvania urologist Philip Hanno served on the FDA’s advisory committee to review the drug’s third application for approval. He was not convinced, and joined five other members in voting against authorization.

“I felt that the risks were significant and they outweighed the benefits for the drug,” he said.

On one measure of efficacy, women who took the drug experienced one half to one additional satisfying sexual encounter per month over controls.

Hanno said he was worried that a woman could lose consciousness while behind the wheel.

“If someone is taking this drug and is driving,” he said, “it could be a problem for people who aren’t on the drug.”

On the other side was Jeanmarie Perrone, an emergency medicine physician and medical toxicologist, also at Penn.

She voted for approval, but did so reluctantly.

“They had met the criteria what they were being asked but the margins were very, very close,” Perrone said.

For example, after an earlier failed attempt, the drug maker was asked to do a safety study with alcohol. Sprout Pharmaceuticals proceeded to conduct such a trial, but tested the drug primarily in men, who are known to metabolize alcohol differently than women.

“They were able to demonstrate safety with alcohol, but maybe not in the population this drug is ultimately intended for,” said Perrone.

Ultimately, the panel recommended approval, 18-6, as long as restrictions were put in place above and beyond labeling. Two and a half months later, the FDA agreed.

A gender politics stormWith the approval, some have questioned the influence of the Even the Score campaign, which raised the profile of women’s sexual dysfunction and argued that women should, like men, have medicines on the market to treat their problems.

The group is a coalition of nonprofits and women’s sexual health advocates that also received funding from Sprout.

“It felt to me that there was pressure on the FDA, on physicians, in a political sense, to serve a need,” said Sarah Smedley, a blogger with the nonprofit MedShadow. “The drug itself is separate from the need.”

Hanno described the atmosphere at the advisory meeting as “kind of intimidating.”

Perrone, too, acknowledged being put in a challenging position.

“You try to pretend like you can think through this in vacuum, and that you’re really measuring risks and benefits and coming up with an objective answer,” she said. “But because they came up with marginal benefit with some risks, the way you ultimately weigh that, there is no exact formula.”

That’s when concerns about an unmet need and equality can creep in, Peronne said.

As an ER doctor, Perrone won’t have to worry about whether she’ll prescribe Addyi. But, she noted, there’s a good chance she will encounter women struggling with the side effects.

“I suspect I will be in a position to evaluate these patients in the emergency department,” she said. “It’ll be something that will be on our radar to ask about when patients come in after a fainting episode.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.