Part One: Even with progressive education funding, ‘fairness’ eludes Berlin schools

Part One of our Berlin series

A view of Berlin, Germany. (Jessica Kourkounis/For Keystone Crossroads)

When it comes to fairness in public education, advocates put much of the emphasis on the resource disparities between school districts.

And this is a hallmark of Pennsylvania’s school system, where leaders allow school funding to be based largely on zip code. In Pa., the state’s wealthiest districts spend an average of $3,000 more per student compared to the poorest districts.

But imagine a system where school funding is not only equalized, but progressive — where the greatest resources are spent in the schools facing the toughest challenges.

Would issues of fairness be solved?

In this three-part special series, Keystone Crossroads travels to Berlin, Germany to explore such a system, where, in short, the answer is ‘no.’

The ‘social wall’

Andreas Rissmann is standing on the borderline where the Berlin Wall once stood. All around him lies what used to be known as the “death strip” — the heavily guarded no-man’s land where scores of defectors were gunned down by East German soldiers shooting from Cold War-era concrete watchtowers.

Today, it’s a leafy, well-manicured park.

But, even though the Wall was turned to rubble almost 30 years ago, a dividing line still exists.

Rissmann lives about a block away from the site of the former wall in an apartment in Gesundbrunnen, a neighborhood in the city’s Wedding section.

“There are people who, when they look this way, they think, ‘Oh my god, Wedding,’” said Rissmann, with mock disdain.

To many, Wedding is the wrong side of town — with some of Berlin’s highest rates of poverty, unemployment, and migrancy.

And the schools carry a stigma too.

Rissmann is a native Berliner, a single father who’s had a string of manual labor jobs. He sends his 6th grade son to the school in Wedding closest to his apartment, Vineta elementary.

“When my son started school, I was asked to which school I would send him, and when I answered, ‘Vineta,’ they said, ‘For God’s sake, you can’t do that.’”

He would ask, “‘Why?’ What’s wrong with the school?’”

“Nobody was able to explain,” he said. “They would say, ‘There are too many foreigners. There is too much this, too much that.’”

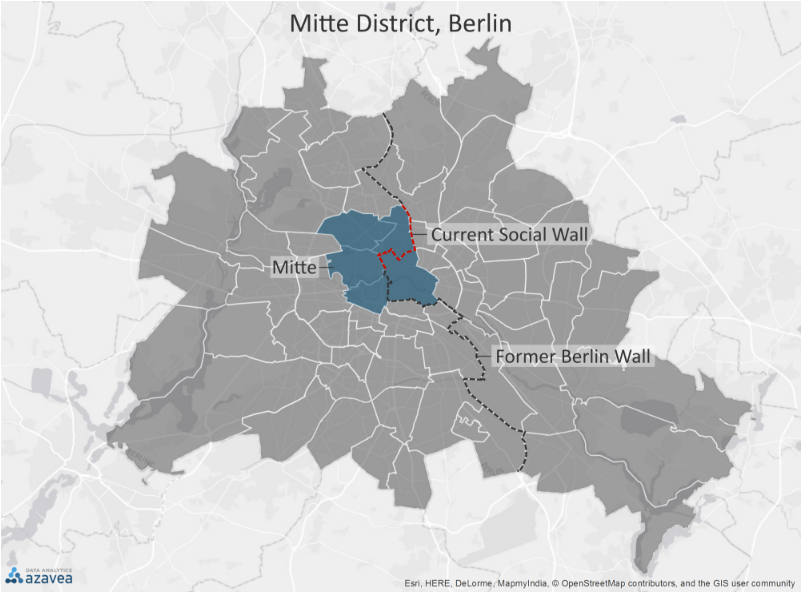

The neighborhood where Rissmann lives is part of a larger district in Berlin called Mitte, which is unique because it encompasses two stratified worlds that literally fall on either side of the former wall.

Westerners have to flip their logic about which is which. The part that was formerly East Berlin is the wealthy side, filled with posh flats, boutique shops, and trendy restaurants. It’s the main downtown section of the city that saw a huge influx of development after German reunification in 1990.

Of the 100,000 people living there before the wall came down, officials estimate that 90,000 have been displaced by a more well-off segment of the population.

The part of Mitte that used to be West Berlin, where Rissmann lives, has historically been a working-class neighborhood home to immigrant communities. And it largely remains so.

“Where there had been the former wall between East and West, is now a social wall,” said Matthias Brockstedt, a doctor and public health official in Mitte.

Dr. Matthias Brockstedt explains the “social wall” that divides Mitte, and reflects on how language development in early childhood affects the rest of a person’s life. (Jessica Kourkounis/For Keystone Crossroads)

Brockstedt’s staff examines every five-year old in the district for school readiness. In much of the Mitte district, the former Berlin Wall runs along Bernauer Street, and Brockstedt sees staggering differences depending on which side the family is from.

“If you are north, it’s a pure Turkish area with low-income parents. If you are 100 meters to the south, you have high-performance parents with academic backgrounds coming in from Bavaria and other parts of Germany,” he said. “It’s a walking distance of five minutes, but still a completely different world.”

The grand plan

Dividing lines like this occur all over the globe. And they’re often taken for granted as an inescapable truth: Life isn’t fair, and neither is the difference between school systems.

It’s the notion that underlies Pennsylvania public schools, where school resources mostly depend on the amount of money a district can raise via property taxes. In Berlin, though, that’s a dynamic that the politics won’t allow. “The idea is that it doesn’t matter where you come from, you can do whatever you want. And it doesn’t depend on the amount of money your parents have. This is the promise we give,” said Maja Lasić, who represents Wedding in Berlin’s Parliament for the Social Democrats, the country’s mainstream left-wing party.

That promise means Berlin — which is one of Germany’s 16 states — takes the opposite approach to Pennsylvania when it comes to school funding: all money is raised centrally, and resources are distributed to schools based on student need. This progressive funding model has been a boon to schools in Berlin’s poorer neighborhoods, which receive a baseline of staff and resources that would make them the envy of many of their counterparts in Pennsylvania.

Germany’s expansive social safety net also ensures that when students arrive for school, they are less likely to have some of the deficits related to deep poverty in the U.S.

Jeffrey Butler, a Michigan native, has been a sociologist in Berlin for three decades.“If you’re comparing the situation in Germany to the United States,” said Butler, “you will probably never find an area in Germany that compares to something like the inner-city in Detroit or Flint.”

But this doesn’t mean that schools in Berlin’s poorer neighborhoods have been relieved of inequities. There’s still a clear line between haves and have nots, and schools in poorer neighborhoods face a myriad of struggles that additional resources haven’t been able to quell.

For example, within the schools in Wedding, Berlin’s government specifically added teachers to help boost German language skills for the large numbers of students whose families predominantly speak another language at home.

But based on his office’s interviews with students, Brockstedt doesn’t believe this was a worthwhile expense.

“There are 50 teachers more in this area just for language proficiency,” he said. “Fifty teachers for five years, and it didn’t make a difference.”

Brockstedt would like to see that funding redirected into in an even greater commitment to state-subsidized early childhood and parental education — which are already both more widely available in Germany than in the U.S.

But he admits that even with these extras, many schools would still suffer a disadvantage because they draw from such a concentration of poverty.

Lasić, the politician, agrees. And using the “social wall” at Bernauer street as an example, she says Berlin still has a long path to a truly fair public school system.

“If you ask me what is the major problem of our educational system in Berlin, it’s the segregation,” she said. “We simply still do have segregation since depending on the income, most of the people live separately.”

In an attempt to remedy this income segregation, about a decade ago Lasić’s party began advancing a plan that was put into effect only in Mitte.

“We have the possibility to mix from the higher income and lower income families,” she said. “That was the idea.”

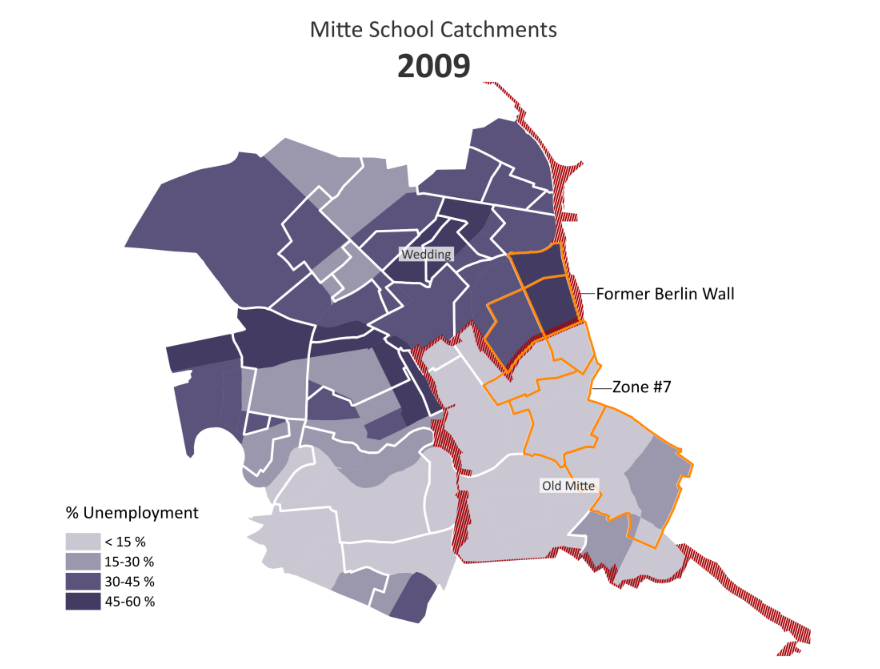

Elementary schools were grouped into different clusters, and the idea was that all parents could opt to send their kids to any of the schools in their assigned zone.

In Andreas Rissmann’s neighborhood, which proved most contentious, the zone boundary was drawn around three schools on his side of the “social wall,” and four schools on the wealthier side. The zone was labeled #7 on the government maps.

In the rendering below, the lines show how the school catchments in Mitte were segmented in 2009, before the integration effort. The orange lines show the area that became zone #7. Percent unemployment is used as the best available proxy for the socioeconomic status of neighborhoods.

In theory, the politicians hoped the schools would be integrated in a way that would spur positive change for all.

“Everybody expected that it would be hard,” said Lasić, with a long exhale. “But they decided to try it anyway.”

So how’d it go?

For some parents, like Rissmann, the idea of mixing student populations was not controversial at all.

“That’s what I try to instill at home,” he said, “what I have tried to teach from the beginning: kindness, politeness, tolerance.”

But for many others, the plan proved too difficult of a pill to swallow.

In part two of this series, we’ll further explore Berlin’s school integration plan, and the blowback that ultimately crushed it.

Some interviews were conducted in German. Translations and other reporting support by Nanette Kröker.

Read the full series — The Social Wall: Universal lessons in Berlin’s attempt to integrate schools

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.