Remembering a coach and a gentleman as another year of high school sports begins

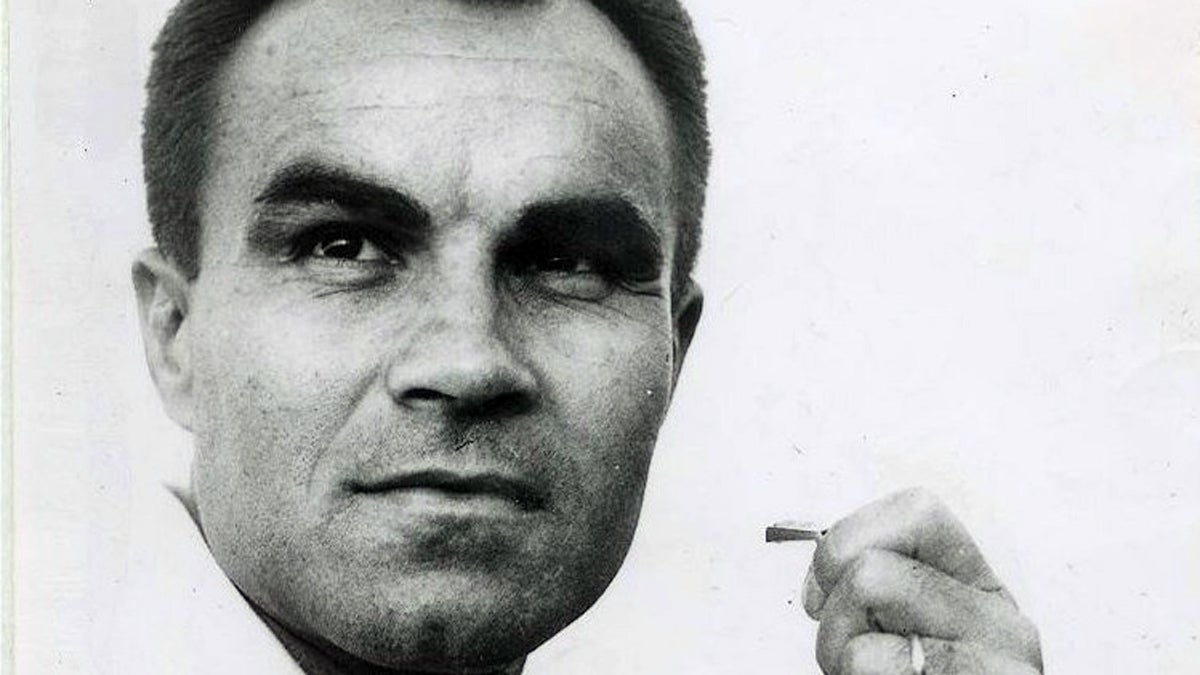

Steve Padjen

At the time, we boys thought camp was all about football. We had that wrong. Years later, we came to understand that Coach Steve Padjen had been teaching so much else. As this summer of 2016 ends, as another year of high-school sports commences, I can only hope kids are playing for someone like him.

The letter runs to three faded pages.

“Blocking is the greatest offensive weapon. Tackling is the greatest defensive weapon … You can harden your body for bumps and bruises by rolling on the grass. Wrestling is fine … Use high knee action in all running. Run, run, run, and run some more.”

And there was this:

“Be faithful, courageous, and cooperative.”

I’d completely forgotten about that letter, its envelope postmarked July 1, 1965, and bearing a five-cent stamp, until it was recently found in my mother’s basement. Above the return address of Hanover (Pa.) Senior High School is typed “Coach Padjen” — Steve Padjen, the head football coach. His mid-summer missive went to everyone who had signed up for pre-season summer camp.

At the time, we boys thought camp was all about football. We had that wrong. Years later, we came to understand that Padjen had been teaching so much else. As this summer of 2016 ends, as another year of high-school sports commences, I can only hope kids are playing for someone like him.

“Be a builder — not a wrecker … Have pride in all that you do.”

During the 1950s and ’60s, Padjen had a statewide reputation. His record over 11 years in Hanover, a small town amid southern Pennsylvania farm country, was 77-33-2. He groomed half a dozen guys who made “Big 33” all-state teams. With the rest of us he somehow made do. In August we all boarded the bus for a site on the edge of town that otherwise served as a Boy Scout camp.

“I am hoping that each boy, despite his size or class in school, will report with the attitude that he can and will make the varsity squad.”

I presented at my first camp, in 1964, as a 14-year-old sophomore quarterback. I weighed all of 130 pounds, suffered asthma attacks until the first frost killed pollen-bearing plants, and mended the fractured temples of my athletic glasses with ankle tape. My adolescent voice broke as I tried to bark signals. Padjen smothered his laughs. And those times when I completed a pass, not many, he gave me an “attaboy.”

“Have confidence. Believe in yourself.”

Camp ran for a week. We practiced up to four times a day in the close heat and slept on bunk beds in open-air cabins. Each evening we spread our sweat-soaked uniforms over the grass to dry. With the morning dew, they became only wetter — and chilly, too. Oh, the sensation of stepping into a clammy jock strap.

“You will go as far as you want to as an athlete, but it takes work, sweat, time, and sacrifice in term [sic] of denying yourself certain pleasures right now.”

Playbooks in hand, we would sit in the shade of a tree to which Padjen affixed a chalkboard. The X’s and O’s he drew still live in memory: 30-counter pass — fake to the right halfback diving off tackle, then to the fullback off center, drop back and look for the right end running a post pattern.

“If you want a job at a particular position, you must earn it … Be a good student and school citizen … Lead a clean life all year long.”

I know. Times have changed. Back in the day, a coach could still say, “Walk around town — the auto won’t strengthen your legs.” That reciting the Lord’s Prayer in a pre-game huddle might offend anyone would have been unthinkable. No one agonized over something called chronic traumatic encephalopathy — the first confirmed case of such concussive injury in a football player was reported in 2005 — though when as a junior I got my bell rung, Padjen immediately pulled me from play, and that was the end of my season.

Yet if the coach of 2016 is working in a different world than the coach of 1965, the new model can still learn from the old. Steve Padjen set generations of young people on a better track toward adulthood, a track some kids would never have found without him.

It was the man, not the exhortation, that rubbed off. He was trim, straight-backed, with dark, penetrating eyes and jet-black hair combed up in a wave, rather Arnold-Palmer-like. He knew his game, and he knew his boys. He had no use for coaching histrionics, though you would feel his scold if you missed a block and his praise if you dived to clutch a pass. I wonder how many men still hear the gravel and authority in that deep voice.

In his own high-school days, Padjen, the son of eastern European immigrants, was a football and basketball star in Steelton. His father labored in the town’s sprawling steel mill, where the work environment, as a mill worker once recalled it, ranged from “dirty and hot” to “dirty and cold.” The story has been told of a man saved from a bleeding death when the hot rolling stock that impaled his leg instantly cauterized the wound.

School was the ticket to something else. Padjen reached Dickinson College, in Carlisle, on scholarship. He played halfback in college until he volunteered for service in an artillery unit during World War II. Returning to Dickinson, he suffered injuries that ended his playing career. Then he took up coaching after settling in Hanover, initially in the junior high school. His football record there, 22-0-2; his basketball record, 45-5.

“A tough guy who emerged from the Steelton area with grace & dignity & high standards.” A friend I played with, and who went on to become an all-Pennsylvania tackle at Bucknell University, wrote that line about Padjen shortly after his death five years ago at age 87. The tribute continued, in part, “To me, most of his coaching was non-verbal — more from his actions and demeanor. (Did he ever cuss? I never heard him.)”

Demeanor: The season following that first camp, Hanover (the upper classmen, not us sophomore bench warmers) went 10-0 going into a final game against a tough cross-town rival. As stadium seats filled early, people took to standing several-deep at the ropes by the end zones. Final score: 7 to 7. In Friday-night pep talks, Padjen would sometimes say, “Let’s have a good weekend,” meaning the pain of a loss could last through Sunday. How pained was he after losing his 11-0 season? Perhaps not at all. What he wanted more than wins was what he had just seen, a Padjen team playing hard and clean and like brothers. In the locker room afterward, he had nothing to say to his boys except for words of his pride in them. I think I still have some of those words verbatim: “Hold your heads up when you walk out of here.”

The last time I saw Steve Padjen, he was fueling his car at a gasoline station in Hanover. I had stopped there on the drive back to my home near Philadelphia following a visit to relatives. By then he had retired from coaching and his teaching and administrative roles at the high school, but he remained a pillar of the community, teaching Sunday school in a Methodist church, serving on the Red Cross board and the borough council.

It went something like this:

“Mr. Padjen, hello.”

My hometown friends and I, when young, considered “coach” an exalted form of address. But now only “Mr.” seemed right. I suppose I hadn’t seen him in at least 10 years, but I didn’t get a moment to introduce myself.

“Rick!” he said instantly.

He could be terrific like that with names, and it didn’t matter much if you happened to play football as he got to know you in high school — or if you had played but were no great shakes, which may be the most charitable thing to say about my own brief stint on the gridiron. He made kids feel they mattered. He managed to do it again when they’d grown up.

“Heh, it’s great to see you! What are you doing these days? Are you still living around Philadelphia”?

We shook hands, and walked over to my car so he could see my family: my wife and our son and daughter.

They met a gentleman. He acted as if he was truly moved to see them. I believe he was.

It was not the time or place to linger, and I can’t recall just what I said to convey to the children, then starting to play their own sports, the stature of the man who was greeting them so warmly. Something about his lasting influence, I guess.

I must have been hoping a bit of Steve Padjen would rub off on my kids, too.

—

Richard Koenig is a NewsWorks contributor and the author of “No Place To Go,” an Amazon Kindle Single concerning the need for better sanitation in the developing world. He lives in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.