Greg Gianforte and the need for civic education

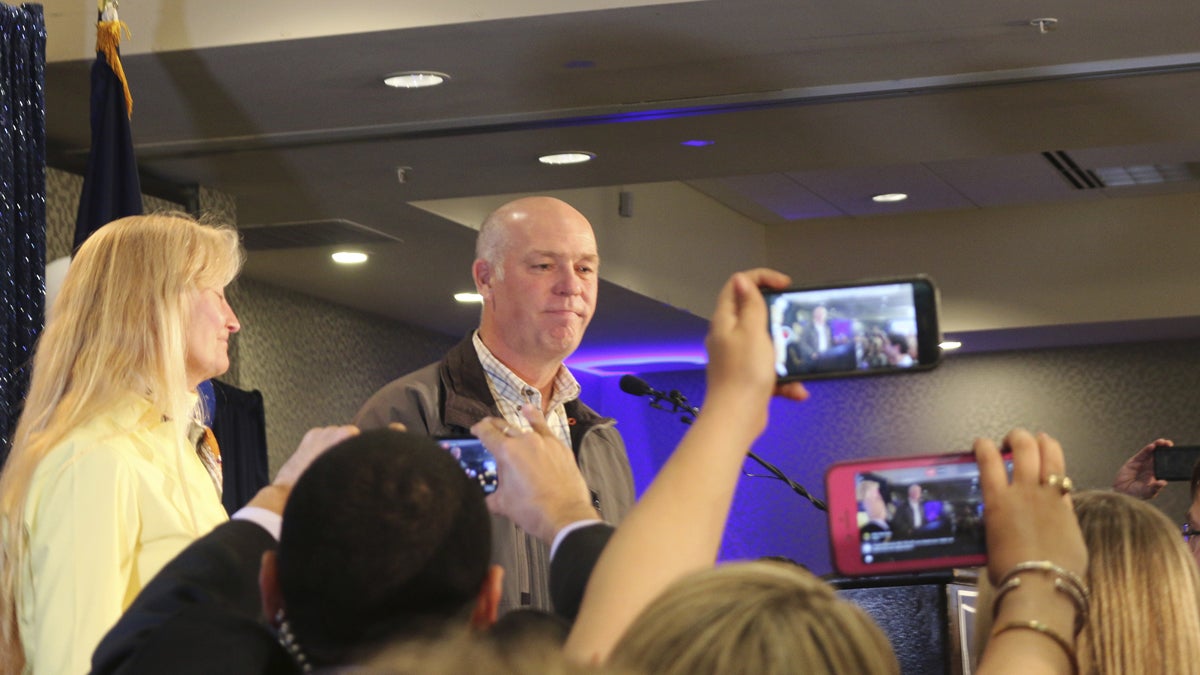

Republican Greg Gianforte greets supporters at a hotel ballroom in Bozeman, Montana, on May 25, after winning Montana's sole congressional seat. In his speech, Gianforte apologized for a altercation at his campaign headquarters with a reporter on the eve of the special election. The altercation led to a misdemeanor assault citation. (AP Photo/Bobby Caina Calvan)

Public schools have to teach a better way of behaving in public. Alas, in recent years, there’s very little about preparing them to be citizens, so we can all live in a better society.

Why do we send our kids to school?

To help them get ahead, of course. In our post-industrial economy, everyone knows that formal education is the key to success. So parents compete to get their children into the best schools. And politicians pass laws to insure — in theory — that no child gets left behind.

But schools are supposed to teach us how to get along with each other, too. They’re not just escalators of mobility, helping kids rise — or fall — in the economic sweepstakes. They’re also incubators of citizenship, instilling the skills and habits of democratic life: reason, tolerance, and mutual respect.

And a lot of Americans seem to have missed that lesson. Witness the recent dust-up in Montana over Greg Gianforte, who threw Guardian news reporter Ben Jacobs to the ground during the final moments of his congressional campaign. It’s not just that Montana voters saw fit to elect Gianforte, who faces criminal charges of misdemeanor assault. It’s that many Americans — perhaps, millions of Americans — thought his behavior was perfectly OK.

“Great your reporter got body slammed,” one emailer wrote to the Guardian. “I’d punch him in the nose.” Another said that the whole incident was Jacobs’ fault, for provoking Gianforte with a question about who would lose insurance coverage under the GOP’s healthcare bill. “He shouldn’t poke his recorder in the face of someone,” the writer claimed.

Even some of Gianforte’s future Republican colleagues in Congress made light of the episode, which could earn him up to six months in jail. “It’s not appropriate behavior,” quipped Rep. Dunan Hunter, R-California, “unless the reporter deserved it.” Rep. Louis Gohmert, R-Texas, joked that “we didn’t have a course on body slammin’ when I went to school — I missed that course.”

He probably did have a course in civics, which has been required in most secondary schools for nearly a century. But it’s fair to ask how much we learn from it. In a recent survey, over two-thirds of Americans couldn’t name all three branches of government. And among our young people, especially, there’s been a decline in support for democracy itself.

In a 2011 survey, about a quarter of Americans between 16 and 24 said that democracy was a “bad” or “very bad” way to run a country, up from 16 percent 15 years earlier. A quarter of that demographic also maintained that it was “unimportant” for people to “choose their leaders in free elections.”

And in a 2016 survey, nearly half of Americans agreed that “because things have gotten so far off track in this country, we need a leader who is willing to break some rules if that’s what it takes to set things right.”

Now we have one, of course, in the person of Donald J. Trump. President Trump has flouted democratic traditions at every turn, calling newspapers “the enemy of the people” and likening American intelligence agencies to Nazis. He has urged crowds to beat up people who protest against him. And he has bragged about sexually assaulting women.

But you can’t lay all the blame for our degraded political culture at the feet of our voluble president. He’s a product of television, where talking heads and reality stars engage in a 24/7 slugfest of snark and invective. On the internet, meanwhile, trolls threaten and ridicule each other with reckless impunity.

It’s a fully bipartisan problem, infecting Left and Right in equal measure. On our college campuses, some of the same liberals who mock Trump’s authoritarian streak think it’s fine to shout down anyone who disagrees with them.

What can we do about that? The answer lies in our public schools, which have to teach a different — and better — way of behaving in public. Alas, in recent years, they’ve moved away from that task. Everything is about getting better scores on standardized tests, so our kids can get better jobs. There’s very little about preparing them to be citizens, so we can all live in a better society.

That doesn’t mean schools or teachers should be backing one candidate or party over another, of course. Instead, they need to distinguish between politics — about which reasonable people disagree — and the shared civic norms that make democratic disagreement possible. Our schools’ message should be clear: While it’s OK to vote for Donald Trump — or for Greg Gianforte — it’s simply not OK to act like them.

Gianforte has admitted as much, issuing an apology to Ben Jacobs during his victory speech on Thursday night. “I should not have responded in the way that I did,” Gianforte said, “and for that I am sorry.”

There was nothing from our contrition-free president, other than an obligatory tweet celebrating the GOP’s “great win” in Montana. But unless our young people learn how to behave democratically, everyone loses. This isn’t just about Montana. It’s about all of us.

—

Jonathan Zimmerman teaches education and history at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author (with Emily Robertson) of “The Case for Contention: Teaching Controversial Issues in American Schools,” which was published last month by University of Chicago Press.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.