Dyottville Glassworks artifacts may be below Wynn Philadelphia site.

Wynn Philadelphia says artifacts from Dyottville Glass Works may lie beneath two small sections of its proposed 60-acre casino site.

But the president of the Philadelphia Archaeological Forum, who led a PennDOT dig that ended at the Wynn property’s Beach Street border, believes much larger portions of the site hold artifacts not only from Dyottville, but from Native Americans who lived at the site thousands of years before, and from other industrial uses pre- and post-Dyottville.

“This site is, hands down, one of the most important archaeological sites in Philadelphia,” said the Archaeological Forum’s Doug Mooney, a senior archaeologist at URS Corp.

Terry McKenna, executive vice president at Keating Consulting, Wynn’s project manager, said the potential for discoveries exists, and, if Wynn Philadelphia gets the city’s second casino license, it will be fully explored. But he said a comparison of historic maps to current conditions done by Hunter Research Inc. – a Trenton-based historical consultant firm – has determined that potential archaeology is limited to two sites, less than half-an-acre each, one in the northern part of the property, and one in the southern part.

Hunter Research determined those to be the only portions of the former glass works site that have been undisturbed by more recent activity – Cramp Shipyard. Even within those two sites, “90 percent was disturbed, and 10 percent wasn’t disturbed,” he said.

McKenna said Cramp has already been well-documented. He expects no Native American artifacts to be found, because “the original shoreline (of the river) was west of the property. This is all fill, that was placed in the mid- to late-18th Century.” He also said that most of Dyottville was not located where Wynn hopes to build a casino – 2001 Beach Street and 2001-2005 Richmond Street – just a small portion “trickled onto it.”

Hunter was hired based on Wynn’s directive to be in a position to “get in the ground the next day” if Wynn Philadelphia wins the license, McKenna said.

The casino project will need state permits, so a historical review is required. Since the two sites identified by Hunter are small, construction could begin elsewhere on the site while test pits are dug in those targeted areas to see if artifacts do remain, McKenna said.

Mooney’s said starting construction without exploring a larger area would risk losing artifacts from and information about important pieces of local history. When a historic review is required, the state sets up a committee to advise the process. The members are called consulting parties, and PAF would sign up to be one of them.

It was due to a similarly required historic review that PennDOT hired URS to do archaeological exploration in areas impacted by the improvements and expansion of I-95. And it was in this role that Mooney and others researched the area around the Wynn property, and conducted a dig on the PennDOT-owned side of the Beach Street border. See previous story here.

It was there, eight feet below the ground surface, where they found layers of Native American artifacts, each layer attributable to a certain time period because they are separated from each other by sediments from floods of Gunner’s Run. “It’s the only known stratified resource in Philadelphia,” he said. “It’s one layer of (Native American) occupation on top of another, like layers of a cake.

“We stopped digging at the edge of Beach Street and Richmond, right next to this property. I know it would continue into what is the proposed Wynn property.”

Mooney continued: “There are acres of intact deposits at Dyottville. Acres. And the whole thing sits on top of an intact Native American site.”

McKenna said that while Mooney and the PAF are entitled to their opinion, it would ultimately be the State Historic Preservation Office that would determine whether the two areas pinpointed for further archaeology would be enough. Wynn would be required to follow what SHPO directs, he said. He stressed that the exploratory work done so far is extremely preliminary, and noted that Wynn doesn’t even own the property yet, and the state preservation folks have not been contacted.

This wouldn’t be the first time PAF weighed in on archeology surrounding a Keating casino project in Philadelphia. McKenna was project director when Keating was general contractor for SugarHouse Casino, less than a mile from the proposed Wynn site. The study there went on for more than two years. The historic review process was often contentious, with the consulting parties, including Mooney, pushing for SugarHouse and its archaeology contractor, A.D. Marble, to do more work. See stories here, here and here.

Mooney agrees that later activity caused some disturbance at the Wynn site. Cramp Shipyard had a dry dock there, for example. “But there is no way to know how far down that went. And the area where Dyottville was, was not that heavily used.” Mooney notes that Cramp itself is an important part of Philadelphia history, and some of those artifacts may be at the surface.

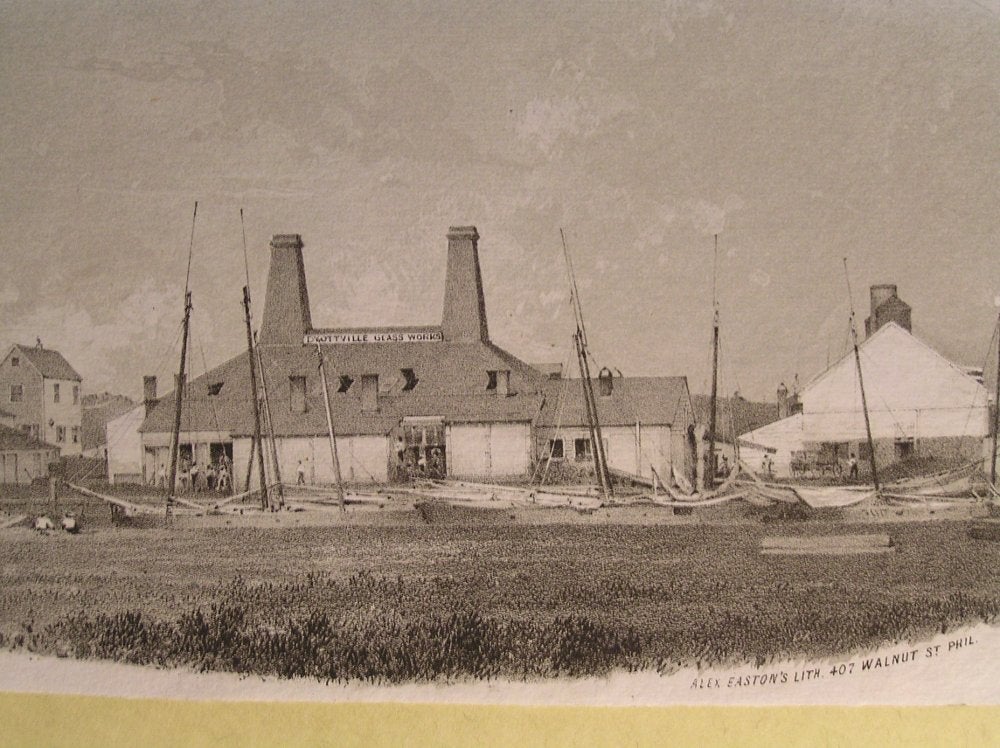

In the 1830s, about 300 people employed by Thomas W. Dyott made bottles for the bootblack and patent medicines he sold around the country. They also lived, farmed, worshipped and attended school within the 300-acre complex that the self-proclaimed Dr. Dyott assembled in hopes of creating his own, self-sufficient society.

Among items unearthed during the Dyottville-related digging done by URS: Glass oven foundations, partial bottles, and items glassworkers made on their own time, including glass canes and witch balls.

Dyott Glassworks was once the largest glass works in the state, but not much is known about the community of Dyottville, which had its own hospital, residences, church, school and likely blacksmith shop and anything else a village would need, Mooney said.

“We know it was there where Wynn wants to build the casino, but in terms of where specific buildings were, we’re short on details,” he said. “It’s still very much a mystery.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.