Crews removing wrecked train cars in Paulsboro

-

<p>Holiday decorations on E Jefferson St. near the site of the train accident (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Work lights falls on the train track leading towards the derailment site. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>The crane is seen at work behind an evacuated house alongside the track on Tuesday night. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>The meeting was held at Paulsboro High School. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Jim Manuel, Chief of N.J. Dept. of Environmental Protection, Bureau Emergency Response shows one air testing devices. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

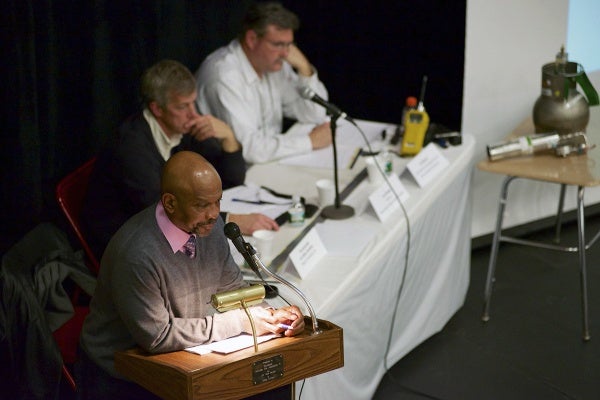

<p>Paulsboro Mayor Jeffrey Hamilton addresses the crowd at the second community meeting on the toxic spill. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Conrail Rep. Rob Fender, Paulsboro Fire Chief Alfonso Giampola and U.S. Coast Goard Capt. Kathy Moore. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Judith Locke, resident of N Delaware St. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

Michael Hamilton, resident of Pine St. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)

-

Joe Eldridge, Director of New Jersey Dept. of Health. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)

-

Around 250 people attended the meeting. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)

-

<p>The meeting was held at the auditorium of the Paulsboro High School. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>U.S. Coast Guard Capt. Kathy Moore talks to resident William Dick, whose employer was closed due to the evacuation order. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Paulsboro Mayor W Jeffrey Hamilton. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Paulsboro Mayor W Jeffrey Hamilton and a resident talk before the meeting. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>An air monitoring vehicle moves slowly over Delaware St. in Paulsoboro, N.J. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Coast Guard says it began "Phase 3" on Tuesday, which involves remaining the train wreckage. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>On Tuesday a floating crane began removing the derailed train cars. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Paulsboro Fire Chief Alfonso Giampola shows a photo taken by first responders of the chemical fog on the morning of the accident. (Bas Slabbers/for NewsWorks)</p>

Crews in Paulsboro, N.J. are now removing the remaining derailed cars onto barges. This latest update was announced last night at the a second community meeting for residents.

The meeting Paulsboro High School was tightly controlled by Paulsboro officials who didn’t want a repeat of the chaotic first meeting that left many residents even more frustrated.

Last night was about reassuring residents that the clean-up efforts are on-track and public safety remains everyone’s top priority.

“Everything we do, we’re getting safer and safer,” stated Coast Guard Captain, Kathy Moore. Moore is part of the Unified Command response team, comprised of the Coast Guard, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), New Jersey Office of Emergency Management, Paulsboro Fire Department and Conrail. A website has been created with the latest updates from Unified Command.

Residents, however, are still anxious about their health and future well being. Confusion persists about evacuation zones and how they were determined.

Toxic spill

On November 30, around 7 a.m., an 84 car freight train derailed on Paulsboro’s Jefferson Street Bridge, sending four cars into Mantua Creek. Three of the seven total derailed cars remain on ground east of the bridge. One railcar was breached, leaking thousands of gallons of vinyl chloride into the air. The vapor plume formed a thick fog and caused an evacuation of 326 homes. Evacuation zone boundaries were drawn where Unified Command found no detectable levels of chemical in the air, plus an added buffer of one block.

Today, eight homes remain evacuated. Last week, vinyl chloride was removed from the breached rail car. On Tuesday, that car was finally lifted from the bridge onto a barge. Phase Two site preparations are now complete and Phase Three is underway, said Moore. Phase Three will involve recovery of the other four derailed cars, three containing vinyl chloride and one containing ethanol. The cars will be moved from the creek with their chemical products still inside.

Risks remain

Dive teams will begin rigging cables and slings around the submerged railcars. The process will take some time, as divers can only do the work if the creek’s current is under one nautical mile, or knot, per hour. Opportunity for such conditions, called a slack water dive window, happens only three times in a day. Once in daylight hours and twice at night. Moore said divers received permission Monday afternoon to begin working at night.

“It’s a very dangerous operation,” she said.

Once secured with rigging, the process of lifting the railcars will begin. A 150 ton crane will lift the cars onto deck barges.

The next vinyl chloride-filled railcar to be removed is one Unified Command has nicknamed “the rocket car” because of its vertical position. It will be the most challenging car to grab and remove, but it is anticipated that the task may be completed by Friday. A third derailed car containing the chemical, but not in the water, will be removed after that.

The fourth car, also filled with vinyl chloride will be next in line. It is the most submerged car. The fifth car, filled with ethanol, will likely be landed on rail rather than a barge, Moore said.

The recovery effort carries a risk of another contamination event. When asked for details on the probability, Moore responded, “There’s no way to quantify the risk.”

She told residents that the operation will be handled in a very slow, controlled manner and doing so with the chemical product still inside the railcars is deemed safer than transferring it to another vessel. Moore said the worse-case scenario would be a situation similar to what occurred November 30.

Environmental tests to continue

What residents want to know most is how detrimental was that fog which enveloped their town and how can they know for sure if they are now safe.

Answers for their initial exposure are hard to come by. Many described being able to taste and smell the chemical, which puts them at unease. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) odor threshold for vinyl chloride is 3,000 parts per million. The greatest risk was when the vapor plume moved through the community that morning, Moore conceded.

Jim Manuel, Southern Region Chief for New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) told residents that initial readings were done by a hand held air monitoring device which tests for a range of volatile organic compounds, including vinyl chloride. Tests done by air sampling devices specific to vinyl chloride were not performed until later in the afternoon.

Information from those first readings is not available because they were either they were observed but not written down by the technician or reported to command center by radio or phone, Manuel explained.

When asked whether such reports via radio or phone were recorded by Unified Command, he replied, “They may or may not have been at the time.”

Captain Moore was blunt. “I have no record for what those vinyl chloride readings were at this initial incident,” she said.

Real-time air monitoring for vinyl chloride will continue, Manuel assured residents. A total of 281 homes and 23 businesses within the evacuation zone were tested and no levels of the chemical were detected. Outside the evacuation zone, 56 homes were tested by request of their owners with the same result. There are 20 more homes scheduled to be tested.

Paulsboro’s public water supply well will be tested, but Manuel says he does not expect that there will be any negative impact because of its depth and location. The well is situate a half mile from the derailment site. Regular screening for toxins and chemicals, including vinyl chloride are done routinely by the town’s water department.

Mantua Creek and a portion of the Delaware River had been tested following the accident and again when the vinyl chloride was removed from the breached railcar. A third sampling will occur when all of the cars have been removed. A few of the initial samples had shown elevated concentrations of vinyl chloride, but none exceeded EPA ecological screening values, Manual said.

Of the 17 collected sediment samples, three exceeded ecological screening values. Manuel said he expects those levels have now dropped off. There will be another round of sediment sampling, including the creek bottom once all of the rail cars are removed. Soil surface samples have also been tested, with results below DEP residual soil clean-up criteria.

New Jersey Department of Health Director, Joe Eldridge told residents that 24-hour air sampling was done over the weekend in public buildings, including Paulsboro’s four schools and levels were found to be safe. On Tuesday, schools were open again for the first time since the accident.

A lack of accessible data is something most residents find frustrating and is creating a level of mistrust. The first batch of quality check data will be loaded onto Unified Command’s website today. “DEP’s measures were not recorded,” Moore noted.

Health risks

Health concerns linger among residents, many who came forward to describe symptoms they or their loved ones have suffered as a result of exposure to the vinyl chloride plume.

Paulsboro resident Michael Hamilton told the panel his seven year-old daughter suffered from a nose bleed so profuse it required a trip to the hospital emergency room, while his four month-old son is now having difficulty breathing. He says he doesn’t believe reports of safe levels, “What if sometime down the line you develop cancer?” he asked.

Eldridge said a team from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) will arrive in town tomorrow. CDC representatives will be administering a detailed survey regarding residents’ symptoms. The agency is also on hand to “answer a lot of questions about potential effects that you were feeling or will feel,” Eldridge remarked.

Hamilton questioned why the CDC would be on hand if environmental tests have indicated no public danger.

Eldridge responded that the situation requires the CDC’s expertise. New Jersey’s health department deals with “other types of environmental contamination. This is not something that we would routinely handle,” he replied.

William Dick says health issues are troubling, but for him the bigger concern last night was being out of work. The foreman came to the meeting to find out when he and 32 of his colleagues can return to their workplace. The company they work for, Ace Pallet, is in close proximity to the derailment and had been evacuated.

NewsWorks learned that his company was allowed to reopen today.

Conrail Community Assistance representative, Rob Fender, says the rail company has and will continue to provide assistance to anyone with properly documented wage loss claims and health expenses.

Questions remain

Tempers flared as numerous residents demanded to know why Paulsboro, with its long-time history of being a refinery town, was so poorly prepared for a disaster event involving hazardous materials.

It’s not like the town hasn’t seen a derailment before. In December 1994, a Conrail train derailed on West Jefferson Street. One of the derailed cars was carrying liquid propane. Paulsboro Fire Chief Alfonso Giampola said there is a plan in place, but “it’s not something we’ve practiced on.”

Communication snafus were abundant the day of the incident, particularly in getting the word out that folks should stay inside. Giampola said he put out the order to shelter in place prior to 7:30 a.m., but parents wondered why schools were still open when the school day begins at 7:55 a.m. Giampola had no answer.

Parents were particularly incensed that children who walked to school were turned away at the door and made to walk back to their homes, being exposed to the vinyl chloride plume for a second time.

Residents say a better explanation of what “shelter-in-place” means would have been helpful. They were also critical of the town’s “reverse 911” system – a system residents say failed to notify enough townspeople of the derailment and what to do to keep safe.

There was outrage in learning that starting a car that morning could have caused explosions, as several folks said they did not know whether or not to stay or go.

Giampola agreed that the town’s preparedness and early response wasn’t perfect and many logistical questions will be looked into. “We’re working towards a solution,” he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.