The slow but certain rebirth of North Broad Street has seen some surprising transformations and inspired proposals.

A former auto showroom, and later a state office building, became luxury apartments and condos. In recent years, the city’s leading restaurateurs have set up shop and attracted new patrons to the neighborhood. A luxury casino complex has been proposed for the longtime home of Philadelphia’s largest newspapers, and there even seems to be progress lately at the long-suffering Divine Lorraine.

There is also new activity at the site of one of North Broad’s spiritual and physical anchors. While many Jewish congregations left Center City for the suburbs in the 1950s, Congregation Rodeph Shalom has maintained its urban presence at 615 North Broad since 1869. It is now adding a new structure – an $18 million project expected to be completed in April — that will be more accessible, spacious and welcoming for visitors and an expanding membership.

The congregation has always preferred the urban environment, despite the challenges and dangers, including the discovery on Aug. 18 of a murdered member, congregation historian Lee Stanley, in his home nearby. Rodeph Shalom believes that its mission includes helping the community around it, in actions and by its presence.

With glowing glass walls planned for the 21st-century addition, the synagogue will be, as one congregant describes the lighting effect, “a beacon on North Broad Street.”

Early arrivals

Rodeph Shalom traces its American roots to 1795, when members formed the young nation’s first Ashkenazic congregation, with descendants from Germany and Eastern Europe. The founders’ early doctrines included acceptance of members whatever their financial circumstances and those of interfaith marriages – policies that continue today at the city’s only Reform synagogue.

For the first half of the 19th century, the congregation met in different locations on the east side of town. In 1847, a former church building was purchased, refurbished and named the Juliana Street Synagogue.

In the 1860s, the congregation decided to follow the city’s growth west in the Spring Garden section and along the increasingly fashionable northern Broad Street. According to “Frank Furness: The Complete Works,” by George E. Thomas, Jeffrey A. Cohen, and Michael J. Lewis, a prominent member of the congregation – and an icon of American Jewish history — Rebecca Gratz prevailed upon her friend, the Unitarian leader Rev. William Henry Furness, to help enlist his son Frank, already one of the city’s most admired architects, to design the new temple.

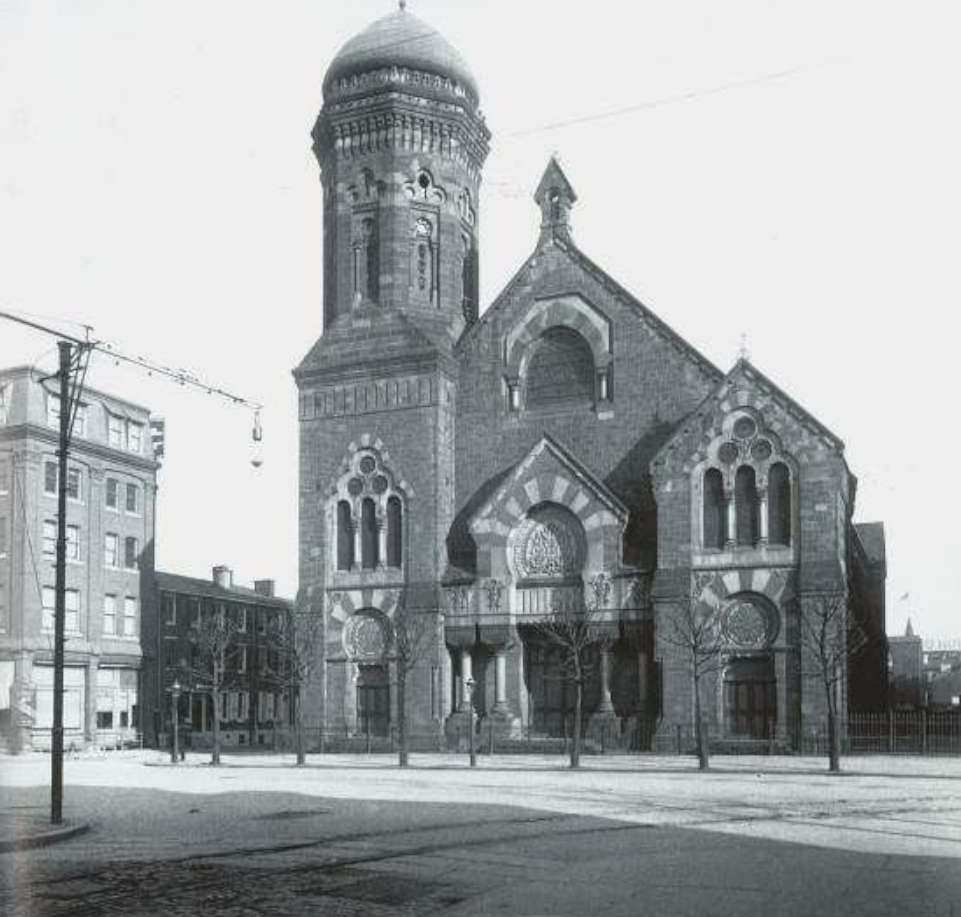

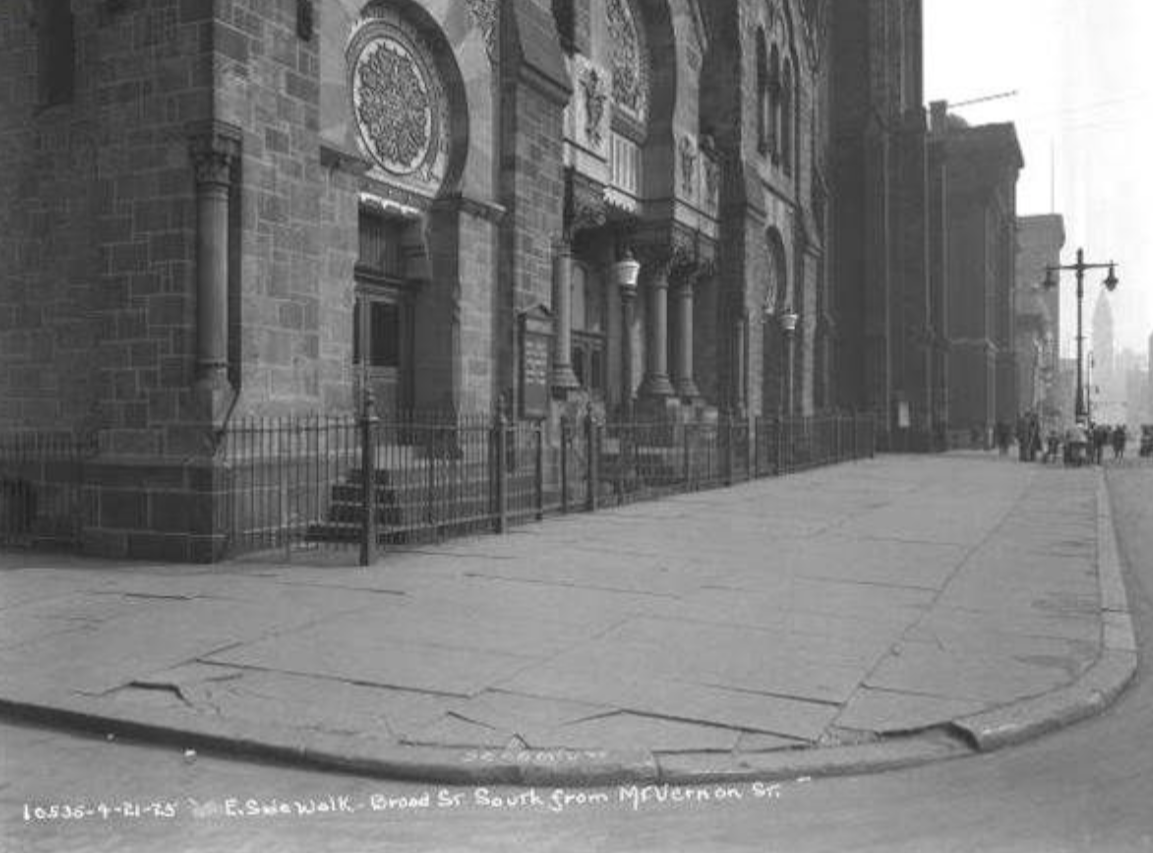

The synagogue built by the Furness firm at Broad and Mount Vernon Streets was brightly colored and in the Saracenic style, with a Middle Eastern tower and dome. But it also had the short columns, high arches, sunbeam motifs and mixed media that characterize Furness buildings. The cornerstone of the new synagogue was laid in 1869. Only a few blocks away, Furness would create his masterwork, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, which was completed in 1876. And he would design homes for many of the synagogue’s directors.

Middle Eastern Art Deco

By the 1920s, the Furness firm’s High Victorian style was out of fashion, and the congregation was outgrowing its Broad Street home. The leaders considered moving to a new address on the recently completed Benjamin Franklin Parkway, said Tom Perloff, Rodeph Shalom’s current director of development and finance. But the accessibility offered by the new subway line, which was under construction in the mid-1920s and opened in 1928, made the Broad Street location more convenient. “I would think from a city planning position, it was the right decision. People lived here, and it was easy to get to,” Perloff said.

Michael Hauptman, a Rodeph Shalom congregant and architect, said the decision was made to tear down the Furness synagogue and erect a new building that would be a combined house of worship and house of learning – the congregation’s religious school had been in a building 10 blocks away.

The synagogue erected in 1928 was designed by Simon & Simon, a prominent local firm whose commissions included the Fidelity Bank on South Broad and the Beaux Arts-styled Strawbridge’s building on Market Street. Rodeph Shalom, the only Jewish institution ever designed by Simon & Simon, has been compared to the Moorish style and the Great Synagogue of Florence. But Hauptman interprets the exterior design as Art Deco “influenced by Babylonian and Assyrian motifs. It’s not Moorish; it’s Middle Eastern,” he said.

The interior is Byzantine, and is as magnificent as the view from outside. The mosaic and mural decoration, stenciling, and stained glass windows were created by the D’Ascenzo Studio of Philadelphia, a competitor of Tiffany. The studio’s work appeared in churches across the country, as well as the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., the Washington Memorial Chapel at Valley Forge, and the windows of Horn & Hardart automats here and in New York.

Rodeph Shalom’s design, Hauptman said, is “the first important complete D’Ascenzo interior in existence.”

In 2004, the synagogue sanctuary was closed for major renovations, and was honored for by Preservation Pennsylvania and the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia for the work performed by Martin Jay Rosenblum and Associates and John Canning Studios. The synagogue was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

Good neighbors

The geographic shift of the Jewish population in the 1950s did pull at Rodeph Shalom. In 1958 the congregation opened a joint educational center in Elkins Park with another Reform synagogue, Kenneseth Israel. The partnership ended when KI built its own facility on Old York Road.

Rodeph Shalom congregants thought about moving to the near suburbs as well. A consultant suggested two options. Because there were already six synagogues in Cheltenham Township, Rodeph Shalom could either move farther out, to Blue Bell or beyond, or “double down on the Center City location,” Perloff recalled. “So we sold that property in Elkins Park. Our decision was that we wanted to be an urban, metropolitan synagogue.”

Congregation president Lloyd Brotman said that while other synagogues followed the migration of their members, Rodeph Shalom still had a large Center City contingent.

The other reason for staying in the city, said Rabbi Jill Maderer, one of the synagogue’s three spiritual leaders, was the congregation’s mission of “social justice.” The community surrounding the temple includes both a growing, vibrant neighborhood and a struggling neighborhood. The location, she said, is “an opportunity, both metaphorically and physically, to be right in the middle of all that and have a chance to really roll up our sleeves.”

Support for the community included the recent establishment of a farmers market to answer the needs of North Broad’s food desert, where fresh, affordable produce is not easily found in local groceries.

On opening day for the farmers market last July, “we had many people from the community,” Brotman said. One longtime neighbor told Brotman that Rodeph Shalom had a long tradition of filling the needs of area residents. “He told me that his mother and her friends still talk about how they came to the synagogue to receive dental care in the 1950s. So we’ve always had an impact on the community.”

Meeting new needs

The design of the new structure addresses the desire to be a welcoming presence on North Broad Street, as well as other important goals of the congregation.

“At the top of the list,” Hauptman said, “we needed to have a building that was accessible and safe. Our 1928 building was neither.” For members and visitors with mobility problems, getting around the Simon & Simon building has been a challenge.

The congregation has also run out of space in the old building. With 1,119 families and with 300 children in the religious school this fall, classrooms are overflowing. On Sunday morning, when the school and adult educations are in session, “we use every inch of this building, and there are people in the hallways,” Hauptman said. “The new addition will solve that problem – for a while.”

To take on the task of creating “a 21st century addition to a historic building,” Hauptman said, the congregation chose a firm known for contemporary and forward-looking designs, Kieran Timberlake.

Richard Maimon, a principal at KT and a Rodeph Shalom congregant for nine years, is lead designer. Neither he nor the firm had ever designed a synagogue building before, though they have worked on religious spaces.

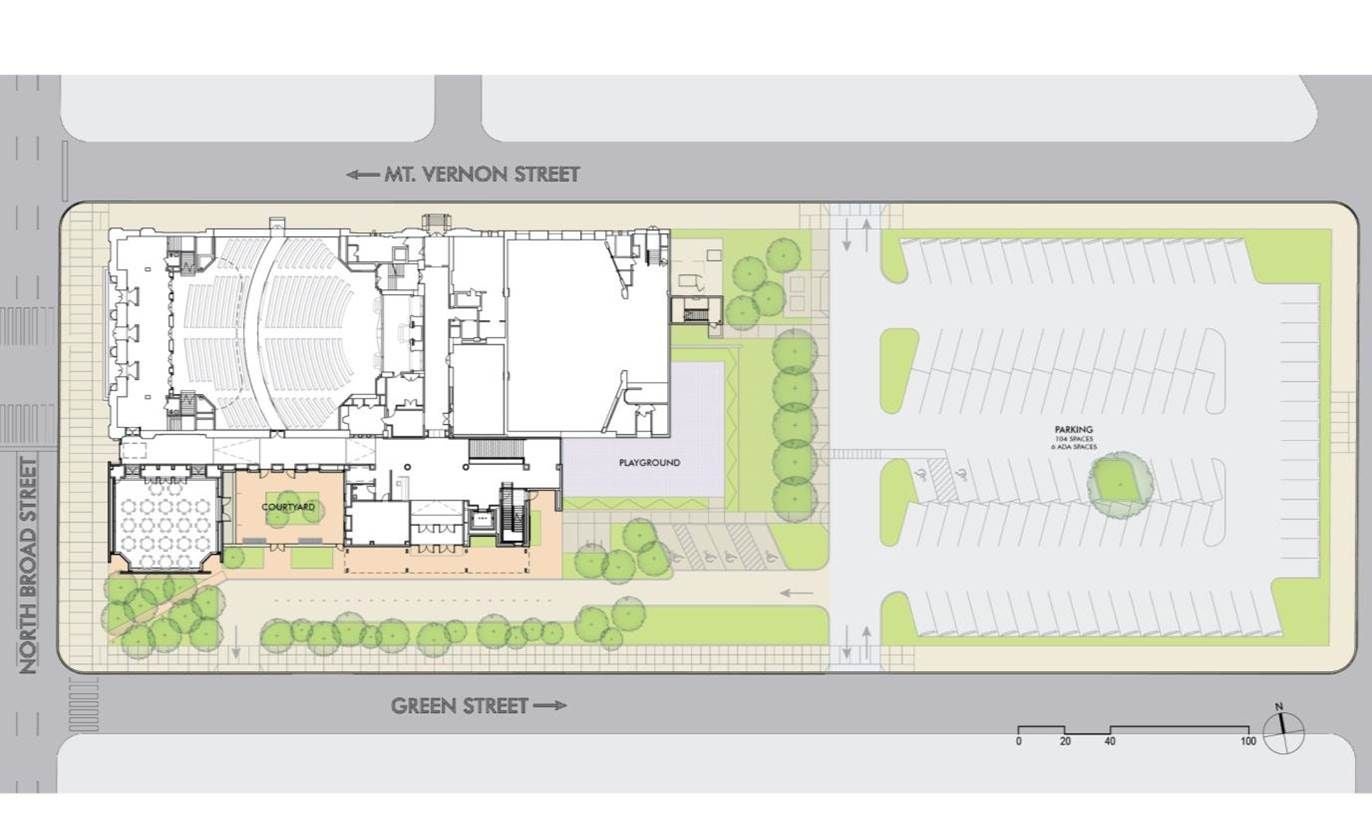

Maimon began a master plan for Rodeph Shalom five years ago. “We investigated ways to provide more connectivity between all the components of the synagogue: the religious, social, educational, and administrative, and to look at some increase in space.”

The goal was also “to present a more welcoming face. The original building is beloved,” Maimon said, “but it is quite cold and closed to those who pass by.”

Meetings with the West Poplar neighbors reinforced that awareness, Perloff said. “Their big concern was to get rid of the chainlink fence” surrounding the synagogue parking lot. To be part of the community, “you have to open up, they told us. And we responded to that.”

To soften the exterior, the firm Studio Bryan Hanes has designed an urban landscape of trees and plantings along Green Street and in the rear of the building, which will beautify the perimeter and address stormwater management at the site.

Building design

The new building will provide 17,000 additional square feet for the congregation. The offices for the clergy will move from the old structure into the new, allowing for the return of seven classrooms in the Simon & Simon building. The new building also will include a “community space” for social events and ceremonies, a seminar room, additional space for the synagogue’s Philadelphia Museum of Jewish Art, and an outdoor courtyard. “This is going to change everything about how we use the building,” Hauptman said. “There will be all these spaces where we can gather. That sounds sort of unimportant, but it’s all about spending some time here, and meeting people.”

Making the style of architecture complement the Simon & Simon design was the larger challenge.

“There was a lot of discussion about what we wanted this building to look like,” Hauptman said. “We wanted it to be sympathetic with the existing building without trying to copy it.”

The height of the building was determined by the desire to keep the old building’s stained glass windows visible on the south side. “We didn’t want the addition to block that view. We created a challenge for the architects to put an addition on our building but keep that elevation visible,” Hauptman explained.

For the community room on Broad Street, the congregation wanted a space that was private enough to avoid distractions from passing traffic and pedestrians. So the designers selected channel glass – interlinking columns of glass squeezed together – that would be translucent.

“We have lights built into them, so the building will glow all the time,” Hauptman said. “This is what we keep referring to as a beacon on Broad Street.”

The corners of the building will be transparent so that passersby will be able to peek in and congregants will see out. The old building has no public space in the entire building that allows a view of the outside; every room has stained glass or is windowless.

The design process for the new building included meetings with and approval from the Philadelphia Historical Commission, Maimon said. In addition to maintaining the southern views of the stained glass, the design includes stone material that works well with the limestone of the old building.

“We designed the massing with the proportion of the windows and walls and the skyline of parapets in the spirit of the original building,” Maimon said. “But it is done in a way that is abstract and modern. Actually, the imagery is deliberately contrasting as more modern, in order to speak of the congregation as it is today.”

At the same time, Hauptman noted, “there will be lots of places in the new building where you can see through glass to our existing building, so that much of the detail will be seen from many of the interior spaces.”

The architects were also careful to build an addition that does not damage the existing limestone façade. No structural elements of the addition come in contact or bear weight on the existing wall, Hauptman said.

Block by block

In addition to the all the needs it filled for the congregation, a new building also offered “an opportunity for another explicit message,” Rabbi Maderer said.

After searching various sacred writings for appropriate wording, a phrase found in the Torah and other rabbinic literature was chosen as the synagogue’s outward message: “Love peace and pursue it,” which also refers to the name of the congregation.

The finished structure will fit well into the ongoing rebirth of North Broad Street, said Brotman, the congregation president.

“We’re taking an entire block and making it beautiful. The whole corridor is in the process of renovation. It’s all around us,” he said. “Block by block, piece by piece, it’s becoming a beautiful neighborhood.”

Contact the writer at ajaffe@planphilly.com.