Cold monuments versus living testimonies: A civil rights tour

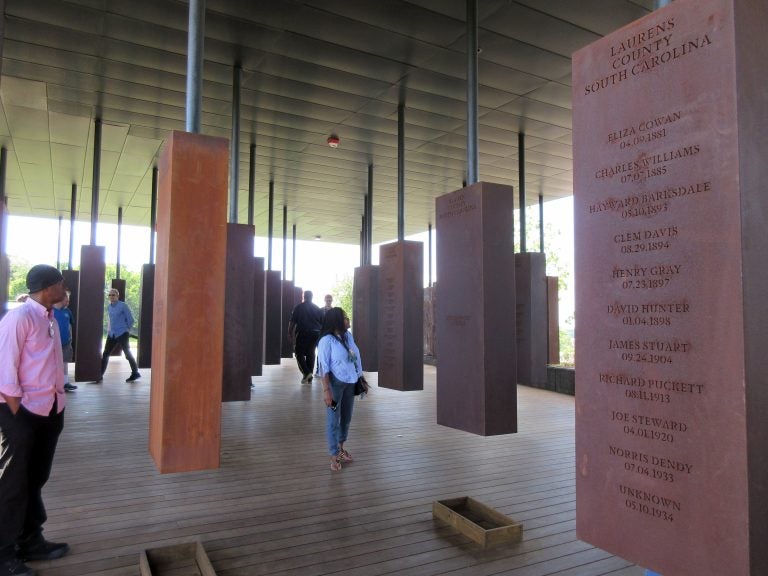

This April 28, 2018 photo shows visitors looking at markers bearing the names of lynching victims at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala. The memorial includes some 800 markers, one for each county in the U.S. where lynchings took place, documenting the killings of more than 4,400 individuals between 1877 and 1950. (AP Photo/Beth J. Harpaz)

Is it still history when it moves a person to tears? When it stirs anger or resentment? Inspires remorse or rededication? Replaces fear with exaltation?

These were relevant questions during a recent weeklong tour of venues important in the civil rights movement.

Departing from Atlanta after pausing at the shrines to Martin Luther King Jr. and his family, 45 teachers and I traveled to Montgomery, Selma, Birmingham, and Tuskegee in Alabama before moving on to Memphis, Tennessee, and Little Rock, Arkansas.

We explored comprehensive museums dedicated to retelling the struggles and victories of the movement — including the National Voting Rights Institute and Museum in Selma; the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute;, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (and its associated museum) in Montgomery; the museum at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis; and, of course, Central High School in Little Rock.

Our mission was to recapture the history of a movement behind the headlines and headliners.

I had assigned more than 200 pages of historical reading to set the context for our exploration, but it fast emerged that this was going to be something more than an accumulation of references for presentation in classes. One might almost imagine that the members of this tour had, through re-enactment, stepped into the throes of the movement itself. They were mightily moved and powerfully resolved to take on the injustices of the world.

That is the story of this “workshop experience.” Against a background of people deliberating over the significance of memorials, it became quite clear that it is not the cold monument but the living embers of civic commitment that most eloquently relate the meaning of community.

A powerful example emerged at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. There is a movement afoot to rename the bridge, since as a memorial to an icon of the Ku Klux Klan it offends folk of tender sensibilities. In our discussions, however, we observed that at the time of “Bloody Sunday” and its aftermath, what was etched in national consciousness was the courage of those who crossed the “Edmund Pettus Bridge.”

Renaming it would not only strip a Klansman of a memorial but would also obscure the memory of determination and resolve of those who sought to change the civic plot line. What mattered: the cold monument or the living testimony?

Two other things touched us deeply. The first was the recognition of how King’s emergence in the bus boycott was sparked not only by Rosa Parks’ spur-of-the-moment resolve but by a decade-long labor to lift consciences to the pitch of resistance. In that context, it became clear that King was a draftee, pushed in front of a parade that had been long forming in his absence. That punctuated part of what we had been seeking, the “foot soldiers” of the movement, whose sacrifices, resourcefulness and resolve constituted the true foundation of the civil rights movement. We learned that the victims of the lynchings, the discrimination, the oppression – nay, the terrorism – were not mere helpless vulnerables in need of rescue. They were, rather, a people who had persisted under extraordinary duress to heights of accomplishment that must be celebrated.

There were countless examples of the martyred victims of the Tulsa genocide throughout the era of Jim Crow and across the land. It dishonors their memories to imagine them as impotent and resourceless. I was able to direct the eyes and hearts of our teachers to the magnificent architecture of Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, built at the start of the 20th century by those supposedly helpless victims of oppression.

Another such moment emerged as we listened to Ranger Jodie Morris recount the saga of the integration of Central High School. Her even-paced and deeply felt presentation conveyed with stunning lucidity the reality of the moment – the decisions made by the students (and their parents and supporters) and by the authorities that transformed what has been transmitted as an epic of clarity into a confused welter of motives, good and ill, which structured deliberations and decisions that tested every inclination to prudence.

This superb National Park ranger made us catch our breath when, after describing all that transpired in the most affecting terms, she added without pause or solicitation that her own father was one of the 18- to 19-year-old National Guardsmen who stood on duty at first to deny and then to defend entry into the school of the children who braved the intimidation of the angry mob. In a flash she made it possible for us to stand on both sides of the drama. We became, ourselves, villains and heroes at once, moved by the pathos.

That moment reflected the culmination of a process that was watered with tears, expressions of tender regard and indignation, and lingering feelings of the need to do something. The cold monuments turned into a living testimony of the power and justice of the civil rights movement.

William B. Allen, Ph. D., is a member of the board of directors of Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge, which sponsored the civil rights bus tour/graduate program for teachers.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.