City promises calm, prepares for chaos ahead of DNC

Philadelphia police escort a protest march near City Hall. (Branden Eastwood for NewsWorks)

Ask any city official whether they expect trouble with protesters during next month’s Democratic National Convention, and you’ll hear an emphatic “no!”

Ask any city official whether they expect trouble with protesters during next month’s Democratic National Convention, and you’ll hear an emphatic “no!”

“People have a right to express their opinion,” said Brian Abernathy, the city’s first deputy managing director, who’s supervising the city’s public safety response to the DNC.

“Philadelphia is where the Declaration of Independence was signed,” Abernathy added. “The First Amendment is very important to us. We honor our forefathers in how we approach freedom of speech.”

Still, their approach strikes some as so riddled with contradictions that civil libertarians worry trouble is inevitable:

Officials say they aim to avoid arresting mischief-makers and instead treat minor offenses, like obstructing the highway, disorderly conduct and loitering, as city code violations – a civil infraction that carries fines but no criminal record or jail time. Yet prisons officials are ready to reopen the old Holmesburg Prison in case police make mass arrests. The police department has assigned so many officers to DNC duties that court officials have asked attorneys to continue all cases now scheduled during the convention because no cops will be available to go to court.

Officials have pledged to accommodate activists’ constitutional right to free speech. Yet they’re negotiating to secure law-enforcement liability insurance – more commonly known as riot or protest insurance – to cover potential lawsuits arising from police brutality and other possible civil rights violations.

They say they want protesters to feel as welcome in Philadelphia as the 50,000 delegates, politicians and others expected to attend the convention and related events. Yet they will corral them in a “demonstration zone” across Broad Street in FDR Park – largely out of sight and earshot of convention-goers. They also are requiring any activists who plan to rally outside that zone to get permits, even though authorities otherwise routinely look the other way for permitless protesters, so long as they break no laws.

To Lawrence Krasner, the city’s approach to DNC protests is full of mixed messages that promise plenty of police-protester clashes.

Civil rights attorney Lawrence Krasner. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Civil rights attorney Lawrence Krasner. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

“They’re talking out of both sides of their mouth. They appear to be planning for the zombie invasion at the same time they’re saying: ‘None of you are zombies,’” said Krasner, a civil rights attorney who has represented activists in dozens of lawsuits. “So what is it, a zombie apocalypse – or is it a civil democracy where people have the right to free speech? It remains to be seen, because frankly, the city has a long history of not telling the truth about what they’re up to.”

George Ciccariello-Maher, a politics professor at Drexel University, agreed: “Knowing that the DNC will happen only once (here) is a huge incentive for police to push the limits of legality. They see their short-term function as: defuse now and pay the consequences later. They can mass-arrest people, and maybe the city will pay a million in lawsuits later, but that effectively disrupts protests and undermines their momentum.”

But just hold on, says the city.

Preparing for problems doesn’t mean officials want or expect problems, police and city officials say. Instead, it’s just smart planning, they add.

“There’s a protest every day in this city, somewhere, for some reason,” police spokesman Lt. John Stanford said. “So we are prepared, and we know how to work with them.”

City risk manager Barry Scott agreed: “This is not the biggest convention we have in the city, nor the biggest event. We handled ‘Pope-ocalypse’ last fall without a problem. The city is used to handling significantly large events and significantly large crowds.”

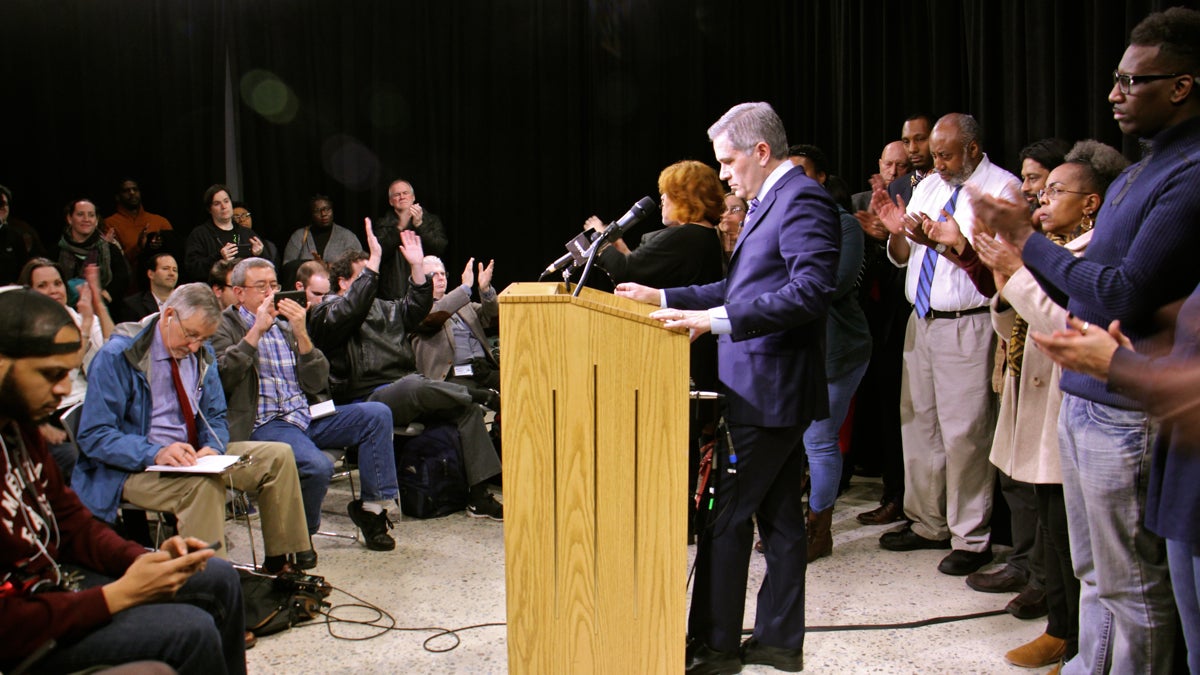

Philadelphia police escort a protest march down South Broad Street near City Hall. “There’s a protest every day in this city, somewhere, for some reason,” said police spokesman Lt. John Stanford. (Branden Eastwood for NewsWorks)

Philadelphia police escort a protest march down South Broad Street near City Hall. “There’s a protest every day in this city, somewhere, for some reason,” said police spokesman Lt. John Stanford. (Branden Eastwood for NewsWorks)

Still, the ACLU’s Mary Catherine Roper, who has been meeting with city lawyers to hash out how the city will handle protesters, was so “deeply troubled” by those talks that she sent Mayor Kenney a letter Wednesday demanding answers to unresolved issues. Among her concerns: A planned crackdown on protesters without permits, the city’s refusal to allow marches in Center City during rush hour, a ban on camping in FDR park during the convention, protesters’ lack of visibility in the demonstration zone, and uncertainties about how outside law enforcement agencies called to assist will interact with protesters.

“We ask for your leadership in ensuring that Philadelphia lives up to its reputation as the birthplace of liberty in America,” Roper wrote in the letter. “At a time when our city will be draped in red, white and blue and on display for the world, we urge you to keep in mind that there is perhaps nothing more patriotic and American than dissent.”

As of Thursday, 19 groups have applied for permits to protest, with applicants estimating protest crowds at a combined 70,000, according to the city.

Will history repeat itself?

History isn’t on the city’s side.

When the Republican National Convention came to Philadelphia in 2000, police arrested 420 protesters – even though authorities then had made many of the same promises they’re making now to watchdogs in the weeks leading up to that convention.

“We were told (before the RNC) there would be no arrests. We were told there would be summary citations. But that’s not what occurred,” Krasner said. “There were 420 people arrested, some of them for incredibly serious charges. Some of them had either million dollar bail or half-million dollar bails. They were charged with multiple felonies, things like riot, causing a catastrophe, risking catastrophe, aggravated assault on a police officer.”

Philadelphia police arrest Becky Johnson during a protest outside the City Hall on the opening day of the Republican National Convention in 2000. She was one of 420 arrested during the convention. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

Philadelphia police arrest Becky Johnson during a protest outside the City Hall on the opening day of the Republican National Convention in 2000. She was one of 420 arrested during the convention. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

The result? Many protesters, including some key leaders, spent the convention behind bars rather than on the street – something critics felt was the city’s goal all along.

Yet nearly all eventually were acquitted of any wrongdoing, leading to civil rights lawsuits that cost the city tens of thousands of dollars.

Other tactics prompted outrage too. Undercover officers infiltrated protest groups to spy on them. Authorities shuttered a warehouse where activists made signs and other protest props – and then destroyed all the props.

Despite the city’s promises that such strategies will remain firmly in the past, watchdogs remain skeptical.

“It will be difficult for Philadelphia to overcome its history of how it handled the RNC 2000 protests. In fact, the city has already begun to position itself on the wrong side of history by trying to pass a municipal anti-free speech measure, by relegating protesters to a so-called ‘free-speech zone’ far from any DNC delegates or TV news cameras, and by selectively denying permits to certain groups such as the Poor People’s Economic Human Rights Campaign, just as it did in 2000,” said Kris Hermes, a legal worker who aided RNC protesters here in 2000 and author of the 2015 book “Crashing the Party: Legacies and Lessons from the RNC 2000.”

Hermes added: “Former Philadelphia Police Commissioner John Timoney (who oversaw the department during the 2000 RNC) is one of the architects of today’s policing model used against dissidents. Sixteen years later, this policing model continues to be used against political movements from Occupy Wall Street and climate justice to Black Lives Matter. The designation of ‘National Special Security Event’ also ensures that the law enforcement apparatus – led by the FBI and Secret Service in concert with Philadelphia police – will be just as robust and repressive.”

Context is key

The DNC comes at a volatile time.

The nation’s worst mass shooting in modern history – 49 murdered and 53 more injured at a gay nightclub in Orlando on June 12 by a gunman who pledged allegiance to ISIS – has heightened security concerns, especially when it comes to large crowds.

Controversial police shootings in Ferguson and elsewhere have left many communities, especially in cities and among minorities, distrustful of police. The militarization of many police departments has deepened that distrust.

Add in political unrest: One month away from the convention, many Democrats remain deeply divided about their candidate. While Hillary Clinton has won enough delegates to represent the party, Bernie Sanders supporters have promised to flood Philadelphia to make their voices heard both inside and outside the convention. Organizers of a “March for Bernie” on July 24 say they expect thousands to attend, and seven of the 19 permit applicants plan Bernie-themed rallies.

Bernie Sanders supporters gather at the Philadelphia Museum of Art to organize for the Democratic National Convention. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Bernie Sanders supporters gather at the Philadelphia Museum of Art to organize for the Democratic National Convention. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

But authorities say they’re ready for whatever happens. Security will be a team effort: Besides local police, agencies involved include the Secret Service, FBI, DEA, ATF, Homeland Security and local, state and federal emergency-management offices, Stanford said.

Police plan to handle protesters with a hands-off approach, unless they try to block highways or commit crimes, Stanford said.

“Our main objective is to allow the folks to express their minds. But we’d like them to do that in a peaceful, respectful manner,” Stanford said. “You can’t be destructive or disruptive. Jumping on the highway becomes a safety concern, because they can create auto accidents or be struck by vehicles themselves. No one hears your message once those things are involved anyway.”

Cheri Honkala already feels unheard, and the DNC hasn’t even started yet.

The city denied her group’s permit application to march on July 25, saying the Poor People’s Economic Human Rights Campaign’s planned rally conflicted with another event and would disrupt afternoon rush-hour traffic on Broad Street.

Cheri Honkala (center) of the Poor People’s Economic Human Rights Campaign says Philadelphia refused her group’s request to protest during the Democratic National Convention. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Cheri Honkala (center) of the Poor People’s Economic Human Rights Campaign says Philadelphia refused her group’s request to protest during the Democratic National Convention. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Honkala, instead, has accused the city of trying to hide its poverty plight. Philadelphia is the poorest of America’s 10 biggest cities, with 28 percent of its citizens living below the federal poverty line, according to Shared Prosperity Philadelphia.

“The worst thing the city of Philadelphia could do right now is to continue to take the position that we cannot march. There’s nothing more dangerous than stifling people’s voices, especially when it comes to poor folks, because the only thing they have is their voice,” Honkala said.

Honkala’s group marched during the 2000 RNC without a permit – or arrests – and plans to march during the DNC, despite the permit denial.

They’re right to do so – and the city would be best-served backing down from any insistence on permits, Krasner said.

“Let them talk. As any parent knows, when people get to talk, they’re less violent. That’s just how it is,” Krasner said. “The real news is that protesters don’t need no stinking permit. The First Amendment is their permit.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.