Christina school board approves Delaware’s first ‘safe zone’ policy for unauthorized students

Listen 1:12

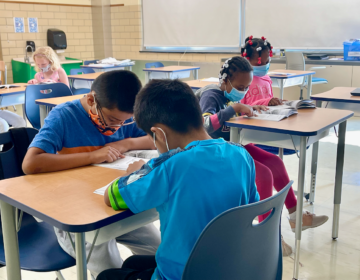

Christina School Disrict's board voted Tuesday to create Delaware's first "safe zone" policy aimed at proving some measure of protection for students and employees from immigration enforcement agents who might arrive at the school door to seek records or access to a student. (Cris Barrish/WHYY)

Christina School District on Tuesday became the first in Delaware to adopt a “safe zone” policy that spells out specific steps to protect students who are unauthorized, as well as employees, if immigration enforcement agents come knocking.

The Christina school board voted 4-2 to institute what members and administrators called a declaration of the district’s commitment to safeguard the constitutionally protected right of unauthorized immigrant children to a public K-12 education.

The new policy also recognizes that “undocumented students do not have absolute protection from enforcement actions brought forth by ICE officials or agencies acting on their behalf. These actions range from requests for information to apprehension.”

Ten members of the public, including Christina teachers and parents, spoke in favor of the program. No one from the public spoke against the policy.

Among their arguments of support, speakers cited the Supreme Court precedent, quoted Biblical phrases and made passionate cries for fair treatment of students who committed no crime but were brought to America by their parents and deserved an education and protection in schools.

Brett Tomashek, a Christina elementary school teacher who also was educated in district schools, drew huge applause after he spoke of the fear by students and their families, in the wake of President Trump’s election in November, that a deportation force would come to their homes or schools to seize them.

“It may be highly unlikely that [federal] agents are going to kick in their doors,” Tomashek said. But what’s a reality, he said, is that “many students around this country and this district think something in imminent, that something is about to happen to their family.”

Susana Lemus, who said her parents were undocumented immigrants from Mexico, fought back tears as she described how important the policy would be to students and their parents.

“Students should not feel intimidated to attend school,” Lemus said. Should the policy be defeated, undocumented students “will continue to hide in the shadows. They will no longer want to engage in any school activities…It hurts to know many kids feel like an outcast.”

The dissenters on the board were George E. Evans Sr. and Harrie-Ellen Minnehan. Evans wanted to make some changes to the language and Minnehan wanted the policy to require approval by the state Department of Education.

Voting yes with sponsor John M. Young were board president Elizabeth Paige, Fred Polaski and Shirley Safer. One seat is vacant.

Hundreds of undocumented students

Though erroneously reported in the local media after its introduction two months ago as a “sanctuary” policy, board members and district officials stressed that it’s only intended to provide some measure of protection to enrolled students and assurance to their families.

For example, a non-student who is in the country illegally cannot seek “sanctuary” or refuge in a Christina school.

Delaware schools do not ask a student’s immigration status, but Young estimated that 200 to 500 of the district’s 16,100 students are undocumented immigrants. About 22 percent of district students are Latino and nearly 12 percent are classified as English Language Learners, spokeswoman Wendy Lapham said.

While school districts in other states have approved similar policies, Christina is the first in Delaware to do so.

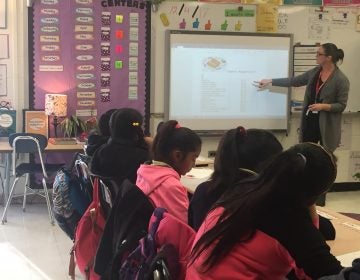

Beyond declaring the district’s support of educating undocumented students, the policy is essentially a step-by-step directive for how employees should respond should U.S. Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents show up at the door to remove a student or obtain records.

District officials and board members have stressed that no deportation agents have arrived at their schools. But with Trump vowing to build a wall at the U.S.-Mexican border as a part of a crackdown on illegal immigration, Christina officials said many parents have expressed fear that their children could be targeted and taken out of schools.

“The recent political environment has created a fear in the community of undocumented immigrants,” Young said last month.

Step-by-step guide for employees

The two-page policy stipulates that should immigrations agents present “a request for access or for information” about a student or staff member’s status, employees:

- are not empowered to accept the request nor block access.

- must declare that such requests “fall under the purview” of the district superintendent so a legal review can “determine the validity of the order.”

- cannot “make imminent threat determinations” or resist if agents enter the school anyway.

- must work with agents to minimize “disruption on campus” and inform the superintendent’s office that procedures were followed.

Should the immigrant agent say the request is “predicated on an alleged imminent threat,” the superintendent’s office must provide an “expeditious response,” the policy states.

The policy also allows “certificated district employees” to discuss the policy in class “provided it is age appropriate.” Students also must be informed that counselors are available to discuss the policy.

Employees are also not permitted to ask about the immigration status of a student or their parents, guardians or relatives.

Employees won’t ‘be human shields’

Tuesday’s vote comes after the district twice revised Young’s first proposal, introduced in February.

Young’s original non-binding resolution to recognize the rights of undocumented students failed 4-3 because some board members feared that employees who resisted attempts by federal agents to seize students or records could be in “harm’s way” and subject to arrest themselves, Young said.

“I took their concerns to heart,” he said in March.

So Young and district lawyers tweaked the language and reintroduced it as an official policy that would also provide instructions to employees.

Board members want to protect students but Paige said some initially voted no because in part because they don’t want employees “to be a human shield in any way.”

That initial vote, and subsequent media reports that the “sanctuary” policy did not pass, had the unintended effect of spreading fear among some families who kept their children from school, Young said. District officials have since reached out to the community to assure families that was not the case.

Young has acknowledged the new policy won’t “provide an absolute measure of protection” because agents could still enter if they chose to seize records or detain a student.

But he hopes that in such a situation, agents would contact the district office and go through proper channels so children “are not going to be snatched out of classrooms.”

Young has also noted that in 2011 ICE issued a “sensitive locations” memo that says agents will not be looking to target places such as hospitals, churches and schools.”

But since that policy does not have an “absolute prohibition,” Young said, that was more reason to craft the policy that passed Tuesday.

When asked for comment, the state Dept. of Education pointed to a letter written by Sec. Susan Bunting on a March 8. She wrote to the state’s school superintendents and charter directors pointing out that “many of Delaware English learners and their families are living daily with anxiety and fears of raids” by ICE agents.

Her letter said the department aims to “support your school communities as you work to protect your students and provide them a safe environment conducive to learning.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.