Bruce Katsiff’s photos explore the grotesque beauty that living bodies can hide [photos]

I witnessed photographer Bruce Katsiff’s fascination with death and the beauty of decay when I accompanied him to Austin, Texas, in 1995. I was there to interview writer James Michener. Katsiff was the director of the Michener Art Museum in Doylestown at the time, and he helped set up the interview.

I didn’t know it then, but in a strange way decay became a theme of the visit. This was a couple of years before Michener died. He was rather ill at the time and spent hours attached to a dialysis machine twice a day, always a long process. He didn’t have many visitors. While waiting to resume the interview, we had a bit of time to explore Austin.

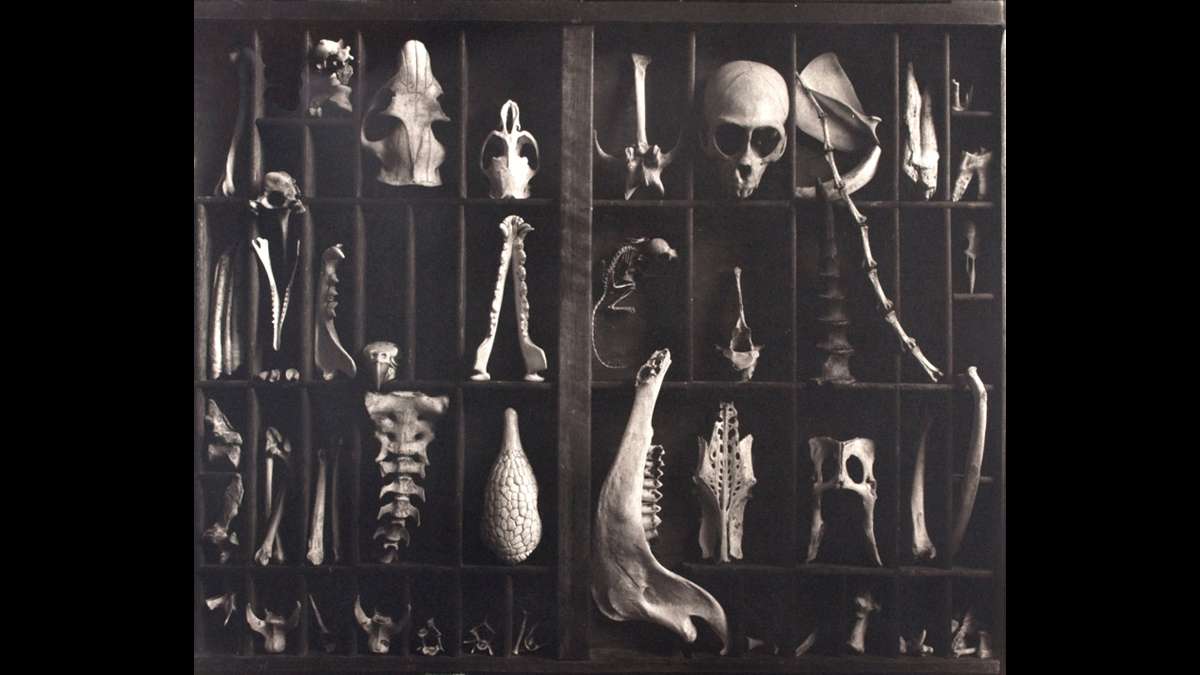

Katsiff skipped the galleries and museums and shopping, and instead drove us straight to an odd store in the unattractive outskirts of the city, near the airport. The shop specialized in selling skulls, bones, claws and feathers from all sorts of animals, from bison to iguanas, from plated armadillos to delicate birds. It was all a bit eerie. Some of those bones, along with hundreds of others collected throughout the years, are the components of his carefully constructed photographs on exhibit at the Delaware Art Museum.

‘Come look at this’

“Nature Morte” is a major exhibition accompanied by a comprehensive publication that speaks of Bruce Katsiff’s interest, both technical and philosophical, in exploring many facets of life.

“I’m fascinated by the fact that some of the bones and skulls are exquisitely beautiful objects that don’t appear until the death of their hosts,” Katsiff says. “We all have these fabulous bones that we don’t see during our lifetime. And they’re going to outlive us, and they speak about the mystery of life.”

His photography is also an act of defiance and provocation. His photographs say: “Come look at this.” Some of the images might not be pleasant, but they’re revealing, he says. “When you make a photo, every object has a certain quality, and things take on an importance in the photo that may have been overlooked in the real world.”

The attraction to his work is also anchored in his unusual techniques. For example, his use of platinum prints gives each photo a rich, almost painterly, quality. “Photography is about information and details, and the purpose is to get as much information as possible. And the best way to do that is to have contact prints, to make a picture that’s the same size as the negative,” Katsiff explains.

To do so, he works with large stationary cameras that have big negatives. He takes many photos with an 8×10, 12×20 or 20×24 cameara. The bigger the negative is, the more detail is revealed. “It’s simply a part of the physics. When you enlarge things you lose detail,” he says.

A decade of old bones

The inspiration for “Nature Morte” started with a deer carcass that Katsiff observed disintegrate into the dirt. His work evolved to include bones and feathers, presented in three-dimensional environments in the style of Renaissance cabinets of curiosity, translating into some striking images. “I spent about 10 years working with the subject matter, so the pictures evolved during that period.”

For the moment, Katsiff is done with bones and death, but he is still looking for what living bodies can hide. Now he is experimenting with large, colorful, multi-layered portraits to probe beyond the surface of facial expressions to reveal the rich internal lives of his subjects.

—

“Nature Morte” at the Delaware Museum closes Jan. 25.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.