Being black and Muslim in the age of Trump

Listen

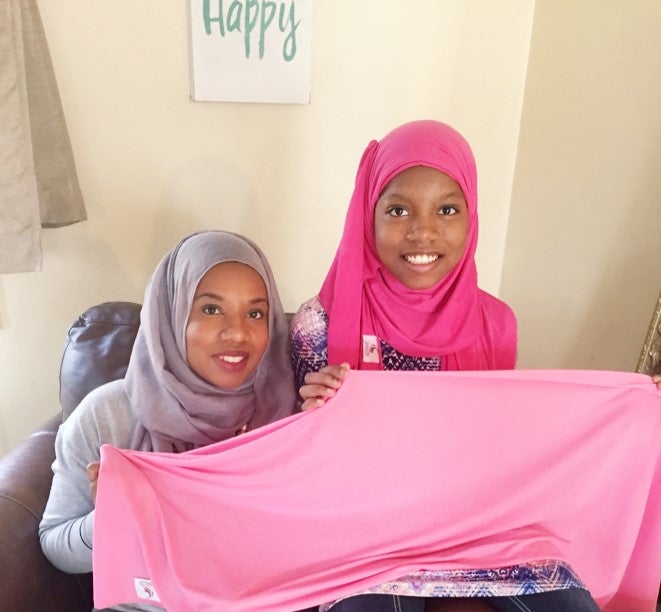

Ameenah Muhammad Diggins (Left) poses with her 10-year-old daughter, Amaya, at their home in Burlington County. Amaya has started a company that creates hijabs for little girls. (Ameenah Muhammad Diggins)

Muhammad Ali Jr., the Philadelphia-born son of the late legendary fighter, was detained in a Florida airport and allegedly questioned about his religion and the origin of his name.

“The immigration guy came over to me and he was like, ‘Can I see you for a minute?’ I said yeah. Sure. No problem,” Ali told CNN last week. “So he asked me, ‘What is your name?’ I told him ‘Muhammad Ali.’ He said ‘How’d you get that name?’ I was named after my father.”

Ali’s mother, Khalilah, was also briefly detained and needed to produce a picture of her late ex-husband to convince U.S. customs officials that she was who she claimed to be.

“So, at that time I figured maybe if I show him I’m really Muhammad Ali’s ex-wife, they’d believe it and make it less [of a] problem,” she said. “Because I never usually have a problem like that. And it’s almost like he didn’t believe me still.”

As Islam has been a part of the national conversation since Donald Trump became president, African-American Muslims — who make up a substantial number of the American Muslim population — face a reality much different from those who immigrate from other nations.

“I am a serial entrepreneur, to put it lightly,” said Ameenah Muhammad Diggins, of Willingboro, New Jersey. Diggins, 40, has been a Sunni Muslim since birth.

Born and raised in Philadelphia, she is one of thousands of black Muslims in the Philadelphia region. Diggins and her husband, among other things, sell real estate and rent out bounce houses for kids’ birthday parties.

She’s worn a hijab since she was a teenager, which she notes was her choice.

“Both of my parents encouraged me to wear a hijab, but it was never forced on me,” she said, sporting a pink hijab. “It was a choice that I made around 13, 14 saying you know what, I want to be known visibly as a Muslim.

“And we had a lot of Muslim friends, so it was kind of like a coming of age for Muslim women. You become more modest and you don the head covering.”

Media definitions

Black women wearing their hijab — a common sight in South Philadelphia — represent a distinct part of the city’s culture. The Pew Research Center’s 2016 Religious Landscape Study estimates that blacks make up 28 percent of American Muslims; other estimates put that number closer to 40 percent.

Farida Boyer is a family therapist and marriage counselor who grew up in West Philly. Like Diggins, she has been a Muslim since birth. From her office in Bala Cynwyd, she said media portrayals have helped to define perceptions about Islam.

“Trying to understand us is a benefit to society,” she said. “I believe that, because of the media, they believe it’s just this extreme religion, and we have these extreme practices …. the reality is that we’re just people too.”

While Boyer and Diggins were born Muslim, most African-American Muslims are converts from Christianity or other faiths. Famous examples include Ali, Malcolm X, basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, comedian Dave Chappelle, and Minnesota Congressman Keith Ellison.

Black Muslims have long spent time on the contrasting spectrums of race and faith. Islam has been an integral part of the black experience since slavery as many enslaved Africans were followers of Islam.

A different experience

Modern-day Islam in the heavily Christian black community, at times, has led to cultural clashes. Since Trump became president, however, being “black” and “Muslim” have taken on different meanings.

“I will say this: Donald Trump has really given civil rights organizations their marching orders,” said Rodney Muhammad, the president of the Philadelphia chapter of the NAACP. He said people come into the organization’s West Philly office every day, asking what they will do going forward; he expects that traffic to continue.

“All you have to do is go back and review what you stand for and look at what they’re doing up there in Washington, and you’ve got your work cut out for you,” he said. “It’s going to be a bumpy ride this four years.”

Born in Chicago, Muhammad was a member of the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s Operation PUSH and helped with his security during his first presidential bid in 1984. It was during the early 1980s that Muhammad joined the Nation of Islam, finding a new purpose that spoke to both his faith and his drive for social justice.

“By 1981, I started making my way to Minister Louis Farrakhan, and then I joined up with him in 1982,” he said. “So I’ve been with him for about 35 years now.”

Led by Farrakhan since 1981, the Nation of Islam has long been known for its activism — including organizing the Million Man March in 1995 — as well as its controversial stances on race. It’s also been accused of anti-Semitism and homophobia. Often diverging in teaching, the Nation is not recognized by a number of mainstream Muslims.

Regardless of philosophy, Muhammad said that xenophobia and discrimination toward all Muslims is nothing new to him — and said the combination of being black and Muslim can lead to being seen as an outsider.

“My situation is more the way [Malcolm X] used to explain it to black people,” he said. “They don’t hang you because I’m a Muslim. They do this to us because we’re black. So our experience, unlike say an immigrant Muslim, is a little different.”

“The treatment, sometimes, among certain leaders in the Christian community — because they’ve been fed a certain way — you can feel a sense of being like an outsider when you actually grew up black along with everybody else in this country,” he said. “But I think it has a lot to do with the way people are being fed.”

‘Enough is enough’

Even in Philadelphia, home to one of the largest black Muslim populations in the country, it is an issue.

Farida Boyer has had moments where she has been seen an anomaly.

“When I became a therapist, I had a teacher who became my supervisor,” Boyer said. “She said that I was the first African-American Muslim that she had ever worked with and she’s been doing therapy for years.

“So, just to say something like that, especially in the Philadelphia area, it was shocking.”

The idea of being seen as a foreigner is also not lost on Diggins, who has two children — 13-year-old Anwar and 10-year-old Amaya. Trump’s since-halted seven-country travel ban confused her kids, and that was emotional for her.

“You get used to there being this negative connotation, but it seems to be, ummm, increasing,” Diggins said, growing more emotional by the moment. “You want children to have a sense of belonging in the country that they’re from.”

“And kids are just kids … they have no sense of knowing what’s going on across the ocean or what’s going on in somebody’s deep thoughts that may want to do something because they have this warped vision of power,” she said.

Diggins said she is, however, encouraged by the level of support that Muslims have received from around the country. After years of harassment, she said, it’s a welcome change.

“I was completely shocked because I grew up with people saying, ‘Go back to effing Iran.’ Somebody yelled that to me when I was 17. And you’re seeing people be like, ‘Hold on a second. Enough is enough. Y’all have messed with these people for too long, and enough is enough.”

Diggins will continue to homeschool her two kids. She will also help Amaya, who has inherited her parents’ entrepreneurial spirit, build her business — Hijabi Fits — which makes and sells hijabs for young Muslim girls.

“She had the idea of starting a hijab head covering line for teens and tweens because most of the scarves that were for adults were too large for a 10-year-old or an 11- or 12-year-old,” Diggins said, noting that her daughter came up with the idea while attending Ali’s funeral in Kentucky last year. “So when she came to me a few months ago, I said ‘That’s a good idea.'”

She has noticed a sea change in attitudes, spurred by the new administration, in which the concerns of minorities are finally being taken seriously.

“So you have this understanding, not just of Muslims, but of African-Americans and we’re not always ‘whining’ about what’s going on. That the struggle often happens at kindergarten and preschool, that there’s a bias sometimes in this country toward our children,” she said. “We’re not just whining. It’s real.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.